In 1967, music and art threatened to take over the world. The Beatles were proclaiming that “All you need is Love”, Jefferson Airplane were chasing the white rabbit down the hole into a magical wonderland, and Pink Floyd were taking us into the outer realms on an ‘Interstellar Overdrive’.

Meanwhile, up on the big screen, Warren Beattie and Faye Dunaway were smouldering as outlaw couple Bonnie and Clyde, while Dustin Hoffman pursued an unconventional love in The Graduate. It was a good time to be young, white, and American.

But for all the hopefulness that emanated from pop culture, real darkness was creeping in at the edges. LSD may have opened up the minds of the flower power generation, but hard drugs lay just around the corner. And as the hippies turned on, tuned in, and dropped out, serious race riots were brewing, and the spectre of the Vietnam War was ever-present in the background. The Summer of Love may have been glorious, but there was a bleak winter ahead.

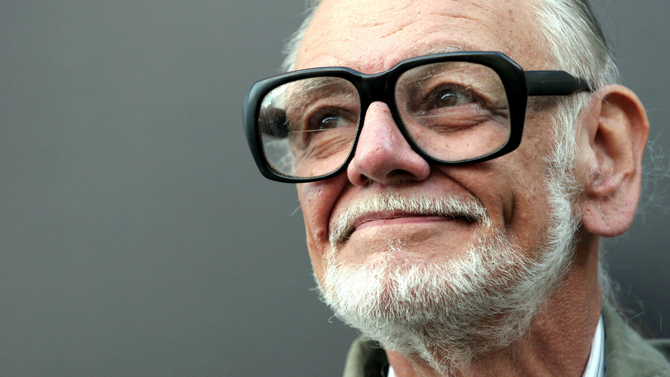

And into this darkness stepped George A. Romero, a film school graduate who’d previously been working on commercials, an experience that would never truly leave him. As 1967 slowly turned into 1968, he crafted a movie that would become a masterpiece, not so much ‘genre defining’, as ‘genre inventing’.

Night of the Living Dead was a modern horror, a nightmare that seemed to tap into something deep within us all, but not cloaked in the Hollywood glitz of Frankenstein or The Wolfman, and more contemporary than the gothic fantasies of the Hammer studio, and Christopher Lee’s leering Count Dracula. In Romero’s hands, we were the monster, either in the form of the shambling husks that stalked the land with an unquenchable thirst for human flesh, or in the shape of our naked desire to survive, and the lengths we’d go to for self-preservation.

Night of the Living Dead finds the Earth infected by a plague from space that has reanimated the dead. Now prowling the streets to feast upon the living, our loved ones have returned from the grave, and those that still live are forced to take up arms against their brethren in a desperate fight for survival. And in one house, a woman, Barbara, partners up with another survivor, Ben, as the hordes of the dead repeatedly assail them, unstoppable in their single-minded pursuit of the living.

It’s a bleak film, right from the get-go, and as it goes on, it gets darker, not just in the literal sense, but in the depths of the human condition Romero is compelled to explore. These are desperate people, who are driven to desperate measures. And as this night wears on, Barbara and Ben are pushed to the limits of sanity, as friends become enemies, and extreme solutions are merited.

By the morning, only Ben survives, having had to take on everyone else in a ‘kill, or be killed’ situation. And as he emerges from this nightmare, he encounters some more survivors. At this point, Romero delivers his final shock to the system; after a night of horrors which has seen our heroes commit terrible deeds, Ben – a black man – is shot dead by the white survivors. Did they mistake him for a ghoul? No answer is ever given. All we are sure of, as his body is unceremoniously dumped for burning, is that this nightmare is far from over.

Romero’s film takes pot-shots at various subjects, but this comment on the race relations of the 60s lingers in the mind more than most. At a time when Sidney Poitier’s erudite black doctor scandalises the neighbourhood simply by virtue of his skin in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), Romero takes it much further; in one view of Night of the Living Dead, Ben is as much of a threat as the undead are. As such, this was a different kind of horror, using fear as a vehicle for satire, provoking us to think, as well as recoil in terror.

Over the years, Romero would up the budget of Night of the Living Dead, and refine its themes. While he made other movies, the epidemic of The Crazies (1973), and Martin (1979), a take on the vampire myth, amongst others, Romero remains most closely linked to the undead. And his follow-up to Night of the Living Dead captures a creative talent firing on all cylinders.

Dawn of the Dead (1978) is a bona-fide masterpiece, an iconic film that entered into our cultural lexicon, and shows no sign of fading away. Even now, its basic premise – a bunch of survivors hole up inside a shopping mall to protect themselves against a zombie outbreak – has been recycled so many times, that it feels like an ancient tale, something that has always been told down the ages. But Romero’s film, despite his usual budgetary restraints, hasn’t lost any of its sparkle, the vivid colours and bombastic soundtrack still hammering home the message he first delivered almost 40 years ago.

And once again, while he’s not afraid to shock or repulse, Romero’s main aim is to make us think, to make us question the world we’ve built for ourselves. As society crumbles, he showcases what he thinks our ultimate reaction would be: a retreat into consumerism. Our heroes barricade themselves away from the horrors of the outside world, and craft a utopia for themselves within the mall. As the world burns, they amuse themselves with fine clothes, luxury food, and creature comforts.

Of course, it all goes wrong, and in a spectacular orgy of bloodletting, Romero crafts an unforgettable finale that lingers in the mind long after the final frames of the film have faded to black. Romero’s creatures aren’t some fantastical monsters, they’re a reflection of us as we are now, sleepwalking through a consumer hell, on an insatiable quest for material goods. It’s bleak, it’s gory, it’s miserable, and it’s deeply funny.

George Romero would return to the dead on several more occasions, with diminishing returns. Day of the Dead (1985) is a thwarted opportunity to up the stakes, let down by serious financial limitations, while Land of the Dead (2005) is a full-throttle tour through the apocalypse, benefitting from a bit more money, but re-treading some familiar ground. There are others, but the less said about them, the better.

But in a sense, Romero was never going to be able to follow up the 1-2 punch of Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead. Tellingly, the former is in black and white, and the latter is in glorious Technicolor, and between them, it’s as if there has been a glorious big bang, and a whole world has been created in the blast. Zombies, survivors, the collapse of society, man’s darker urges, flesh, blood, and gore; George A. Romero gave these things shape and form, and we’ve never bettered his glorious visions.

Now that he has passed on to something else, one can look back at that optimistic age of the 60s, and see Romero as a forward looking prophet, a man who saw behind the cosy veneer into the heart of darkness. He may have given us ‘The Darkest Day of Horror, the World has Ever Seen’, but like his iconic zombies, we’re still hungry for more, and seemingly, will never get enough. Steven Rainey