Final Portrait is actor Stanley Tucci’s fourth film as writer-director and shares with Big Night, his 1996 gastro-drama debut, an interest in artisans and their obsessions; though in comparison, it’s an amuse-bouche.

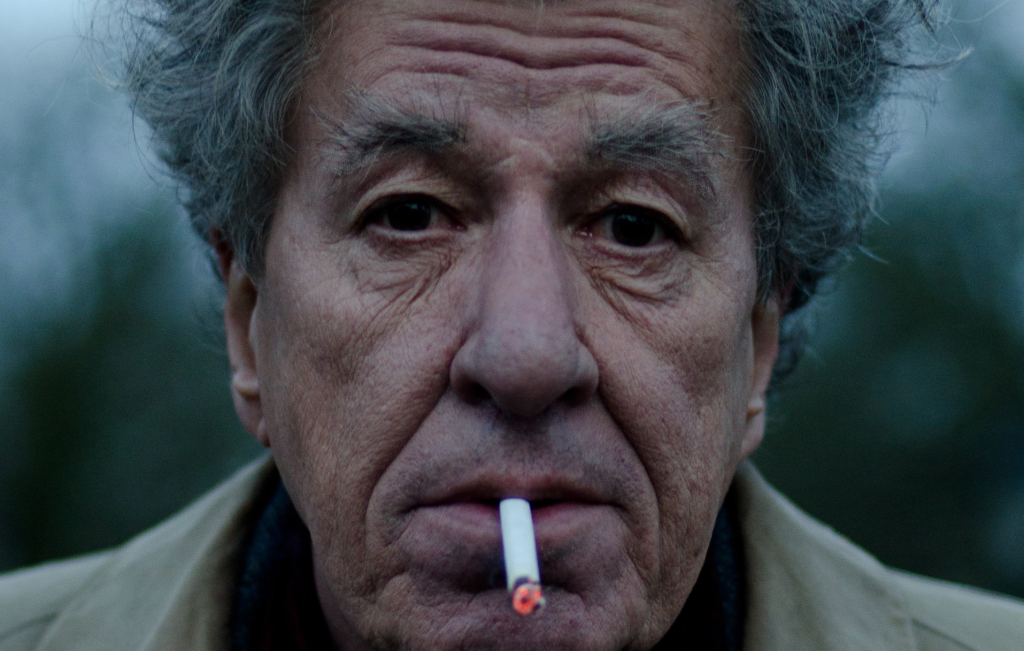

Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti, living in 60s Paris, explains the changes in portraiture philosophy to James Lord, a young American fan and writer who is sitting for one of his own. Portraits used to be finished articles, a frizzle-topped Geoffrey Rush explains, because the subject needed a likeness and a double; the advent of photography has erased that. His portraits are, he admits, essentially unfinished; laboured and inspired glances, bits rather than totality. Final Portrait looks for the universal in the specific too, concentrating on the weeks-long period in which James sat for his portrait, a process with an elastic deadline later recounted in Lord’s book A Giacometti Portrait. But there is also a real hardness to James Merifield’s production design, a detailed atmosphere of artistic messiness, built in layers of grey. Giacometti’s studio, as the cliche goes, is the real star.

Final Portrait is amiable, silly and a little plodding. In concept it’s got the workings of a fun, genteel chamber piece, two creative types locked into a kind of collaboration. There are occasional stretches of the legs, a walk along a graveyard or some wine and eggs in the local cafe, but mostly the film squats inside the painter’s crouched alleyway lodgings, which seem themselves to have emerged out of a painting, or a theatre prop department. Popping in for visits are Giacometti’s wife Annette (Sylvie Testud), mistress Caroline (Clémence Poésy) and long-suffering brother Diego (Tony Shalhoub), a sculptor in his own right.

The film is too gentle to build real chemistry between Alberto and James. Hammer‘s main job is to sit still for fuzzy facial close-ups, and to be fair he’s got the chops for it. Hammer is an A-class talent at standing still; even when in motion, he has the sturdy-oak restfulness of a man unburdened. Rush is having a laugh as Giacometti, Temperamental Artist: dour, cynical, prone to whimsical outbursts. He spits curses as his canvas, takes the piss out of Picasso and burns drawings in a trash can when gets upset. There is more than a little panto to his performance, to which James, forever on the phone pushing his flight back, rolls his eyes in panic and exasperation. The comedy is mannered, safe and bourgeois.

The meat of the screenplay is Alberto and James’ conversations about art and creativity, but they keep it light, and Tucci’s screenplay has a weakness clever-sounding philosophical cuteness (‘when I was young I thought I knew everything; now I know I know nothing’). Taken honestly, there are no real insights here; the pleasure is in spending time with the men and the rhythms of the portrait process, the paint and brush mechanics captured with keen, affectionate photography. Final Portrait could have done with sharper construction itself, but it’s light and lightly amusing. A minor work, as art people say. Conor Smyth

Final Portrait is screening at Queen’s Film Theatre, Belfast and the Irish Film Institute, Dublin.