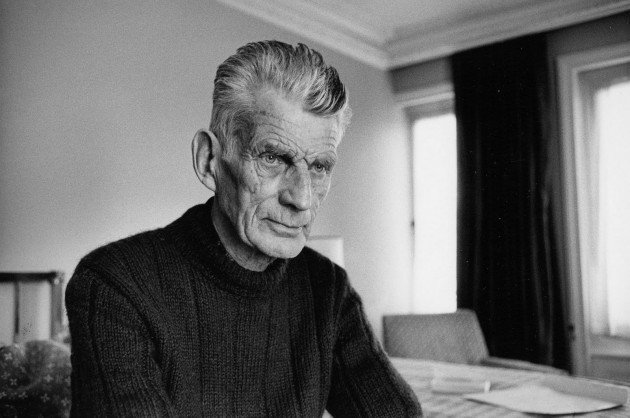

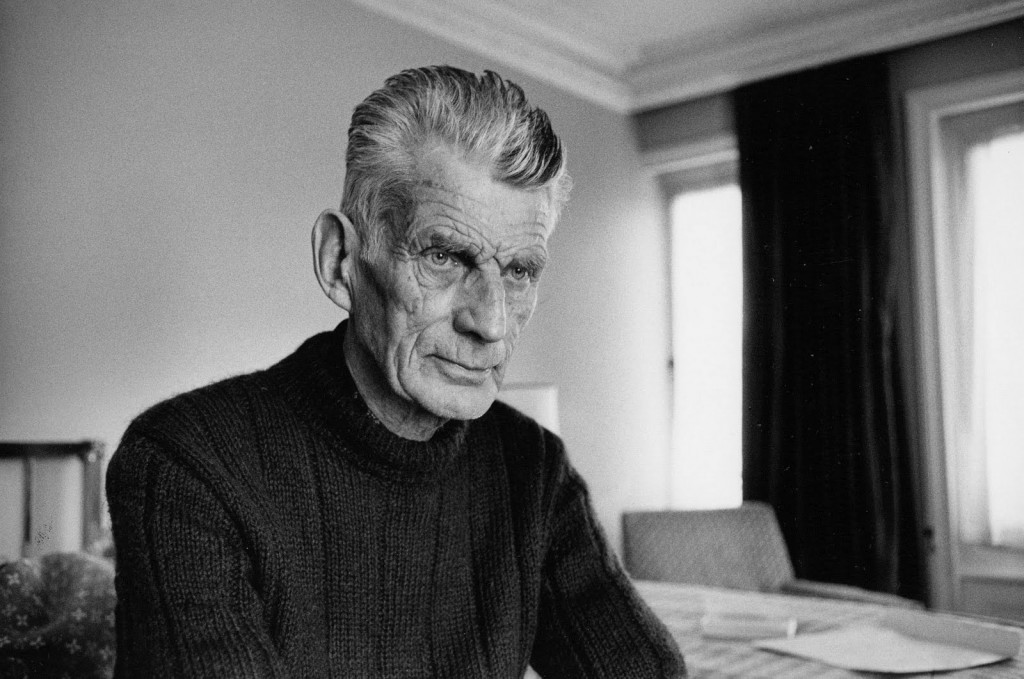

In theatrical terms, Lisa Dwan’s trilogy of playwright Samuel Beckett’s celebrated short plays at The MAC represented a significant first, and in all likelihood, a last. The actress’s stated intention to retire from performing ‘Not I’ by the end of 2015 means that these handful of Belfast shows had an added spice.

It’s hardly surprising that Dwan can see the finishing line for her role as Mouth, as the emotional, technical and psychological demands must surely exact a price. Head strapped to a board, eyes and ears covered, arms immobilized, enveloped in total darkness – this is sensory deprivation taken to extremes.

The only light, a beam that illuminates Dwan’s mouth, signals the start of an electrifying nine-minute monologue delivered at the speed of thought. Mouth’s thoughts are often described as a stream of consciousness, but in reality these are no more than random memory fragments of a cracked mind – mental shrapnel.

Dwan’s delivery has all the rising falling drama of an orchestral score, each phrase is beautifully nuanced and the score punctuated by biting percussive exclamations. Taken together, the shattered mosaic of Mouth’s thoughts reveals a partial portrait of a near-seventy-year old woman; abandoned as a child, shipped off to a religious institution ‘with the other waifs’, unloved, isolated and insensate, but for ‘the dull roar in the skull’ – a constant buzzing.

It comes as a repeated shock to Mouth to realize that she’s not in fact sixty any more, but closer to seventy, as the decades, but little else, leave their marks on her.

Burdened by the guilt that her suffering is a punishment for some crime, Mouth’s childhood recollection of being taught of God’s mercy provokes bitter laughter. Her pleasureless, companionless existence is punctuated by stark recollections of crying to herself, a humiliating court appearance, ranting aloud on rare occasions – ‘always winter some strange reason’ – to complete strangers, unable to properly articulate her sounds. Each one of Dwan’s phrases is emotionally weighted, a remarkable achievement given the velocity of the delivery.

The flashes from Mouth’s disjointed archives of the mind are in the main, however, of ‘walking all her days…a few steps then stop…stare into space…then on…’.

Though Dwan’s sensory deprivation is total – locked into Beckett’s skullscape as it were – the partial sensory deprivation caused by the blackout provokes unexpected experiences amongst audience members, notably the hallucinatory notion that Mouth is hovering randomly back and forth across the stage.

In the end, the light recedes, taking Mouth back into the black void and once more to her silent habitat.

A three-minute pause filled by a lulling drone allows shifting in seats and sets off a chorus of coughers. Once more, light raises the curtains, this time on ‘Footfalls’, another slice of Beckett’s perfectly distilled observations on the realities of the human condition. The faint beam of light provides a spectral carpet for May – a ghostly figure who paces metronomically back and forth, her rhythms constant. May’s chiseled dialogue with her aged mother reveals the plain facts of caring for the fading woman – the ritual injections against pain, bedpan and sore-dressing duties, bed-bathing, lip moistening. Stark as the imagery is, it’s also undeniably moving.

At the same time, a sense of immeasurable distance separates May from her mother. Is the mother in some back room of the house or inside May’s head? With Dwan interpreting both voices, a darkly nagging thought persists that, like Norman Bates in Hitchcock’s ‘Psycho’, May’s mind is perversely fractured in two. Like Mouth in ‘Not I’, May is also burdened with unrelenting thoughts –‘will you never have done revolving it all?’ – and trapped in a daily existence that offers no respite.

In ‘Rockaby’, the only motion is the mechanical rocking backward and forth of a rocking chair, in which an old woman’s quiet fight for more time on this earth, more life, weakens. ‘More!’ she cries at intervals, the strength in her voice gradually dissipating.

The sequins on the woman’s dress sparkle delicately in the light like stars. Light is an essential element of all Beckett’s plays (‘Play’, Beckett’s work from 1963, requires over 240 lighting cues in little more than fifteen minutes) and lighting designer James Farncombe deserves mention for his highly evocative illumination.

In an interview with the author a fortnight prior to these performances Dwan acknowledged the role of light, giving some insight into Beckett’s stagecraft: “I would say that the lighting is the second actor in this. I think the entire production is almost a duologue with light.”

Again, as in ‘Not I’ and ‘Footfalls’, rhythm is also central to the performance as the steady mantra of the woman’s voice, hoping to see another living soul, ‘another creature like herself’, vibrates like a pulse. Eventually, the voice comes to a terminal stop, the woman’s head lolling to one side, finally relenting, finally at rest.

Dwan captures like few actors the spirit of Beckett’s work – his rhythms and accents, his humanity. It’s perhaps no wonder, given that her director for this trilogy is Walter Asmus, long-time collaborator with Beckett. It’s also significant that Dwan was tutored in the role of ‘Mouth’ by Billie Whitelaw, who was in turn coached by Beckett himself.

The first performances of ‘Footfalls’ (1976) and ‘Rockaby’ (1980) featured Whitelaw, who has become synonymous with the three roles interpreted in the MAC by Dwan. However, the Irish actress has since picked up the baton. She’s already left her own indelible stamp on ‘Not I’ and judging by her hypnotizing performances in the MAC, she seems bound to do the same with the other roles.

Beckett’s brave writing demands not only a brave actress, but an intuitive and highly disciplined one. Dwan fits the bill on all counts. In the post-performance discussion, the actress, discussing Beckett’s modern relevance, said to the audience: “I think people are ready for Beckett.’ Lisa Dwan, who brings a sense of discovery to these roles, is leading the way. Ian Patterson