Precursor: the hype was justified.

The long awaited “good kid, m.A.A.d city 2.0” is here, and well, it’s not that. It’s something else.

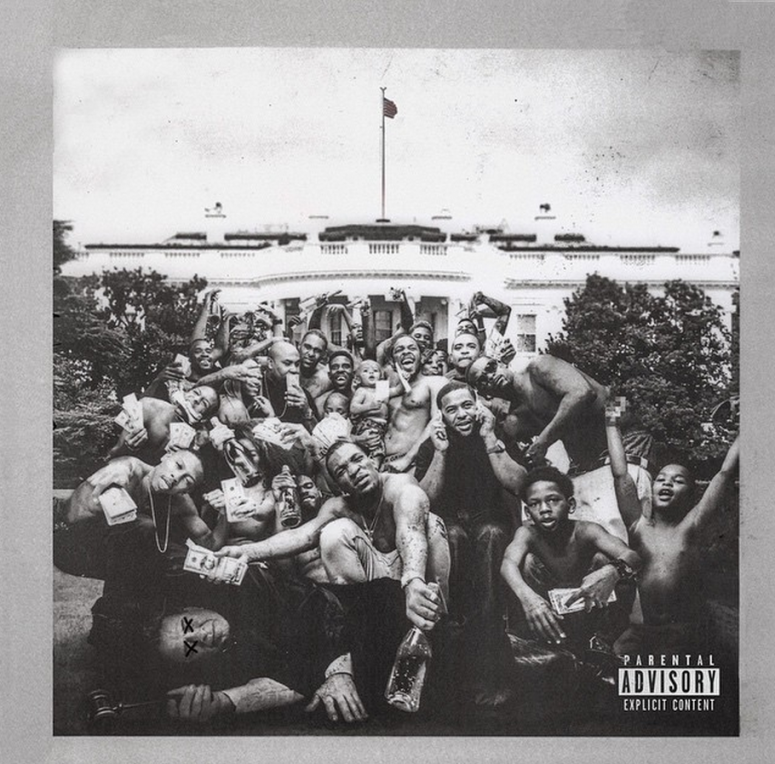

It’s somehow bigger, darker, catchier and more socially significant all at once. Kendrick Lamar’s third studio release To Pimp a Butterfly is all of those things, and nothing like what we expected. Opener ‘Wesley’s Theory’ – featuring George Clinton, produced by Flying Lotus, sampling Boris Gardiner and a voice clip of Dr Dre – is an eye-opening funk monster to end all preconceptions.

Aside from the immediately clear difference in instrumentals – good kid’s slick trap beats a distant

memory now – the main separation between the two albums is their chronology. To Pimp a

Butterfly’s narrative is much more fragmented, lending to the more complex themes explored within

its verses. Good kid’s story of a young Kendrick’s first forays into drugs and gang violence required a

stricter structuring of beginning, middle and end – a veritable children’s story now overshadowed by

his growing up, and his conflicted thoughts on black pride and respectability politics. This is

undeniably a more taxing, and infinitely more rewarding listening experience.

The two singles preceding the record’s early release showcase his schizophrenic thought process

perfectly – the almost masturbatory self-love on ‘I’ and the introspective hatred within ‘The Blacker

the Berry’, in which he examines his own responsibility as an artist in the murder of innocent

teenager Trayvon Martin. He ponders not just how his fame has affected his own life, but those of

his community in Compton, and all across the United States, with particular reference to the

violence in Fergusson, Missouri.

The relationship between gang mentality in young black men and police violence is a theme often

explored on the album, as Kendrick often worries about the image he portrayed on good kid with

songs such as ‘The Art of Peer Pressure’ – the album which became a worldwide phenomenon for its

depiction of a confused black teenager being chewed up by his surroundings. It was not a

glamorization by any means, but he still feels like a hypocrite in his newfound maturity. A poem

which features multiple times throughout, slowly evolving to bookend the theme of each track,

reveals Kendrick’s hindsight and ends with a conversation with his idol, Tupac Shakur (yes, really.)

On ‘Momma’ he thanks his fame and attention, how it helped him escape and simultaneously how it

brought him home, before repeatedly massaging his ego and stating ‘I know everything’ – but there

is a pervasive survivor’s guilt throughout this and many of the other tracks. “You ain’t no brother, you aint no disciple, you aint no friend” he sobs on ‘u’, “a friend never leave Compton for profit”. He is audibly shaken, and drunk, swigging from a bottle between flows. It’s one of the hardest-hitting

moments on To Pimp a Butterfly, and brings the circle of pride and self-hatred started on ‘I’ to a

traumatic close.

The album is a constant pleasure, between Kendrick’s noticeably-improved flows and the stunning

instrumentals, many of which could easily be enjoyed as standalone pieces. ‘King Kunta’ is the

closest thing to ‘Backseat Freestyle’ you’re going to find here, dripping with James Brown-inspired

funk, paraphrasing Michael Jackson and sampling Parliament’s ‘We Want the Funk.’ Singers Bilal and Anna Wise feature prominently on multiple tracks, most notably the luscious chorus on ‘These

Walls,’ also featuring bass extraordinaire Thundercat. Among all the features though, Rhapsody’s

verse on ‘Complexion (A Zulu Love)’ stands out among the best, reminiscent of Jay Rock’s jaw-

dropping additions to the similarly melancholy ‘Money Trees’. And then there’s ‘For Free?’, Kendrick’s remarkable beat poetry piece that is maddeningly different to anything in his discography, enormously ambitious, and simultaneously one of his strongest raps on the whole album. It’s these kinds of moments that elevate Kendrick from his peers, legitimately raising the question – is this man the voice of hip hop in the 21st century? With To Pimp a Butterfly, Kendrick’s case couldn’t be stronger. Aaron Hamilton