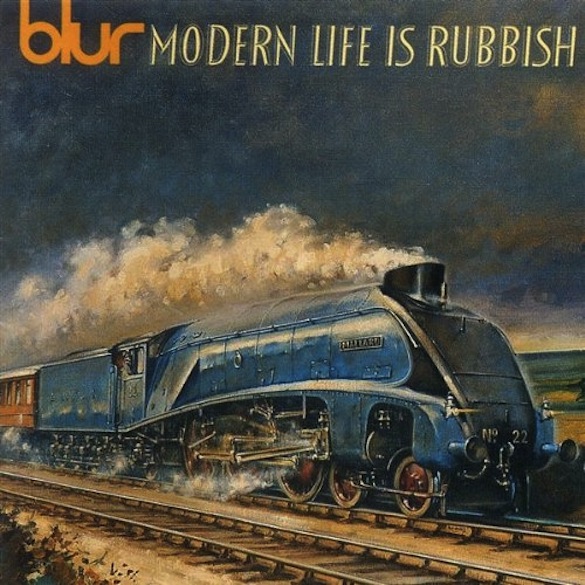

Blur’s Modern Life Is Rubbish is very much an album made under duress. Having toured the US at their label’s insistence, the band found themselves over £60000 in debt with no commercial prospects to make it back. In order salvage some cash, the group released “Popscene”, a punk inspired, horn heavy stomper with hatefully playful lyrics about the music industry. It’s the sound of band taking all of the frustration and rage they been bottling up for years and letting it out in one vicious, beautiful burst. Naturally it tanked and barely dented the pop charts, peaking at number 32. Yet in spite of it’s financial failure, ‘Popscene’ reinvigorated the band and forced them to grow up and forge their own path. Eschewing the predominantly American grunge boom that had hit the UK, the band consciously began writing songs that harkened back to the likes of The Kinks, The Jam and a whole slew of other UK groups. Fighting tooth and nail for every step, the group clashed with their label on this change in direction. There were some lacklustre sessions with XTC’s Andy Partridge and debates as to whether or not Nirvana producer Butch Vig should produce the record. In the end, the band were able to settle on ‘There’s No Other Way’ producer Stephen Street, who would reveal himself to be one of the most important figures in their career. Released in 1993, Modern Life Is Rubbish is fourteen excellent tracks, but really all that was needed was ‘For Tomorrow’. Within it’s first 8 bars, the song manages to shake off all of the doubt and uncertainty left lingering from their previous record and states, unequivocally, that Blur had a lot more tricks up their sleeve. With its flanger driven acoustic sound giving way to a crunching guitar punch, the spectre of Bowie’s ‘Queen Bitch’ hangs like a welcome scent. It’s a clearly defined mission statement and when the final notes fade away, it proves that the band had recreated themselves as something new and thoroughly exciting. It speaks so strongly that it almost removes the need for anything else to be said. But the album keeps talking and talking and somehow manages to get better and better.

The further you delve into the record, the more it gives in return. Be it the punky energy of ‘Advert’ with it’s punchy lyrics and bass, ‘Oily Water’ and its gigantic climax or the sweet than the sugar harmonies that are spread across the album like the finest butter. One element that Blur nail to the wall are the choruses. Listening ‘Villa Rosie’ and ‘Sunday Sunday’, you have to marvel at the groups ability to seamlessly integrate these enormous, swelling choruses into the music with such grace. The way the horns enter into the mix on ‘Sunday Sunday’ it feels as though this joyful marching band has just kicked you door in and started wrecking the place and yet, despite this, all you want to do is dance. Truthfully though, one of the true highlights of the whole trip is a single moment on ‘Colin Zeal’. An early album stromer, ‘Colin Zeal’ features this spider like bassline, crawling up and down your spine while the guitar and drums have this jittery, high treble twitch like a tweaking addict. The whole thing begins to approach the same unsettling region as Manic Street Preachers’ ‘Archives of Pain’ and then the everything stops. A moment before the chorus comes in, all the music stops for a single bar for Damon Albarn to say “…and then he”. It’s jarring and striking and made all the more powerful by the wall of noise that follows it, which washes away all the creeping dread and leaves a more pathetic image in it’s place.

The album is full of moments like this due in no small part to everyone being give a greater freedom to experiment, in particular Alex James and Dave Rowntree. The two play off each other so magnificently and when they’re both given free reign you end up with tracks like ‘Blue Jeans’, ‘Villa Rosie’ and ‘Turn It Up’. Graham Coxon also steps up his game on this record and seems to constantly find the most interesting way of putting guitar into the music. But the real MVP here is Damon Albarn. While on the previous album, he locked himself into a faux Ian Brown persona, here he allows himself to be his own person and is rewarded for it greatly. While he doesn’t showcase the full range of his pipes, he lets the words do most of the vocal work for him. They are these scabrous portraits of an England that’s lost sight of itself in an attempt to become the 51st State. While not every lyric works, the fury is there and is in the process of being finely honed into the weapon it would be on the next record.

But the record does have problems. There are points where songs meld together to an uncomfortable level. All the songs are good as a collection of tracks, but as a whole they do lose of their lustre. The final track, ‘Resigned’, while a decent closer does seem to owe an unfortunate debt to something like Leisure and doesn’t really give the album the send off it deserves. Additionally, the group for some reason decided to close each LP side with a small instrumental vignette. ‘Intermission’ and ‘Commercial Break’ are these strange tidbits that sound like the theme song to the most aggressive circus in history. They’re fun on the first few listens but much like the interludes that plagued 1990s hip-hop, they get old very fast. Their presence isn’t needed and the in case of ‘Commercial Break’ it actively hurts the overall track it’s attached to. Modern Life isn’t the definitive Blur record, but it probably their most significant. It’s the album that released from their youthful bookishness and allowed them to become one of the most important groups in the UK. It’s playful and fun, but unafraid to rip shreds out of that which it loathes. It’s an imperfect record, but a damn fine one. It’s an album that presented the listener with a view of modern life, but it’d be through a different kind of life that the band would launched into the stratosphere. Will Murphy

Read part one of this feature – Will’s look at Blur’s debut, Leisure – here.