Contrary to popular belief, on the 13th of July 1985, Bob Geldof did not turn to a TV camera and shout, “GIMMIE THE FUCKIN’ MONEY!” Instead, whilst imploring viewers to make the phonecall, and being told by BBC TV host David Hepworth that they needed to give the postal address out first, he utters, “Fuck the address, let’s get the numbers.” Hepworth then informs him that they’re going to have to give the address out first anyway, and Bob retires to the background for a moment.

The three other studio guests proceed to read out credit card numbers, with Pamela Stephenson handling England, Billy Connolly taking on Scotland and Wales, before Ian Astbury of The Cult reads out the telephone hotline for Northern Ireland. Of the people assembled in the room, Astbury is the odd man out, nowhere near as famous as the other guests, an up and coming rock star with one hit single under his belt. Later in the day, he’d meet icons like David Bowie and Freddie Mercury. Later still, he’d get the tube back to Brixton.

Given the enormous viewing figures and cultural significance of Live Aid, this is probably the biggest audience Astbury would ever appear in front of. But away from the huge stadiums and gleaming teeth of the corporate 80s rock brigade who would commercially benefit from the televisual spectacle, Astbury and The Cult were about to embark upon their own rock and roll odyssey, a journey that would take them across the globe, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. It wold owe little to the mainstream popularity of MTV friendly music, but for a brief moment, The Cult would be at the vanguard of a branch of gleaming gothic rock. And just for a moment, it would conquer the world.

Goth has its roots in post-punk, with the label being attached to Joy Division, Siouxise and the Banshees, and The Cure. All these bands had been emancipated by the promise of punk, but rather than go down the angular and socially conscious avenue of post-punk, they embraced a different sensibility. For Joy Division, it was the brooding soundscapes of David Bowie’s ‘Berlin’ trilogy. For the Banshees, it would be the swampy, spooky menace of The Cramps. And for The Cure, it would be a churning and desolate psychedelia, an atmospheric sound that would reach its apex on their fourth album, Pornography, in 1982.

Along the way, these bands would inspire a host of imitators, and by the early 80s, goth would be a successful underground scene, dominating the indie charts, and occasionally making inroads to the mainstream. Clad in white facepaint and black clothing, the early goth scene met with frequent mockery from the music press, its narcissistic self-obsession making it an easy target in the face of much more ‘worthy’ music. Whilst bands like Gang of Four and The Pop Group tackled the injustice of modern society head on, the likes of Bauhaus and The Sex Gang Children revelled in a Bowie-esque sense of dark glamour, uninterested in fighting the system, in favour of indulging in decadent romance.

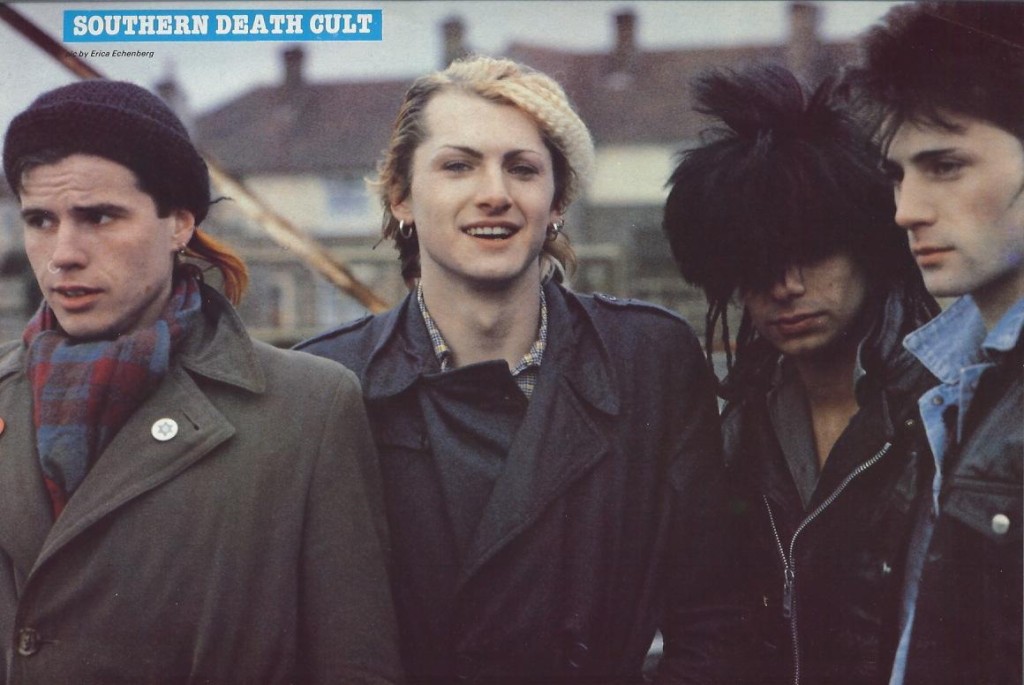

Originally from Cheshire, Ian Astbury had become a prime mover in the goth scene with his band The Southern Death Cult. But where a majority of goth bands were noted for their sullen stage presence, Astbury was something different. Toying with Native American imagery, the stage was a place of catharsis, the tribal drumming and slashing guitars providing a backdrop for Astbury to live out his psychosis in front of an audience. This was visceral, frequently powerful music, dominated by the booming vocals of their frontman. To the uninitiated, it looked like a full blown rock show.

‘Rock’ had become a dirty word for many in the early 80s, calling to mind connotations of pre-punk indulgence, but The Southern Death Cult built their reputation on their incendiary live show, with Astbury marching across the stage, a bona fide showman in a sea of introverts. Their debut single ‘Fatman’ openly toyed with rock dynamics, but still had one foot in the post-punk world, too esoteric for mainstream acceptance. But right from the beginning, it was clear that Astbury’s ambitions were greater than to be seen wearing white facepaint in London’s Batcave Club, ground zero for the goth scene.

Around the same time, Mancunian guitarist Billy Duffy was serving his time in Theatre of Hate, a rockabilly influenced post-punk band led by bleach haired frontman Kirk Brandon. Duffy already had a fairly impressive CV, having played in both Slaughter and the Dogs, and Ed Banger & The Nosebleeds. A young Stephen Morrissey was briefly singer in the latter, and through Duffy, Morrissey was introduced to Johnny Marr, a childhood friend.

When Astbury and Duffy came together, a meeting of minds occurred, both possessing a similar aesthetic, a bombastic sound that overtly showed traces of a world before punk. By 1983, both The Southern Death Cult and Theatre of Hate had come to an end, and the seeds were sown for one of the greatest rock bands of the 80s.

Originally called Death Cult to capitalise on Astbury’s critical success, their debut EP was a thing of wonder, a crashing, shimmering slice of rock that exuded confidence from the opening seconds. Still wearing the trappings of goth, it was moody and atmospheric, but the gloomy introspection was crushed by the huge guitars of Duffy, and the even huger voice of Astbury. A follow-up single, ‘God’s Zoo’ toned down the rock, in favour of slinky, danceable funk, but the wheels had been set in motion for something big. Appearing on Channel 4 TV show The Tube, the dropped the ‘death’ from their name, and became simply The Cult.

Meanwhile, in Yorkshire, goth had found an unlikely powerbase in Leeds. Amongst the hordes of black clad musicians, one band had already set themselves apart from the crowd, by virtue of becoming invisible.

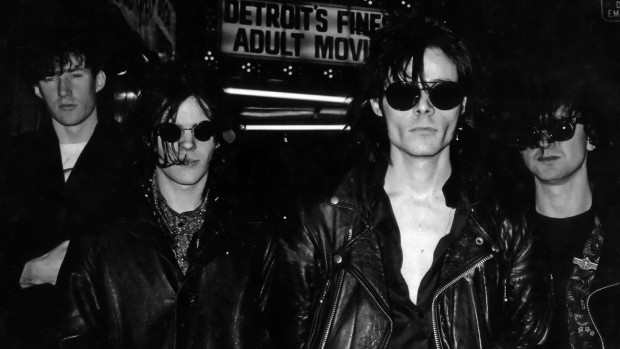

Starting out as a joke, The Sisters of Mercy (pictured, top) utilised a distinctive live show which found them absolutely smothered in dry ice, whilst stark lighting cast ominous shadows in the fog. Centred on the charismatic Andrew Eldritch, The Sisters had made their mark on the UK indie scene with a series of beautifully packaged singles, each one adding to their sense of mystique. Drawing upon Spaghetti Western soundtracks, the lyricism of Leonard Cohen, and the dark, druggy atmosphere of The Doors, their tinny, rattling sound had won them a legion of fans, elevating them to the front of the goth pack.

The addition of guitarist Wayne Hussey marked a significant change in the sound of The Sisters of Mercy. The Bristolian guitar player had enjoyed a taste of success with Pete Burns and Dead or Alive, but by 1984, he’d brought his studio experience to The Sisters, adding shimmering 12 string guitar and classic rock dynamics to their sound. Instantly, the band turned from an abrasive underground act, to a band with serious commercial potential. Where early singles had rattled along in a pleasingly primitive fashion, their debut album First and Last and Always almost rocked, the slinky chimes of Hussey’s distinctive 12 string guitarwork giving the record a dynamic sense of beauty and power. With First and Last and Always hitting number 14 in the UK album charts, The Sisters of Mercy stood on the precipice of commercial success.

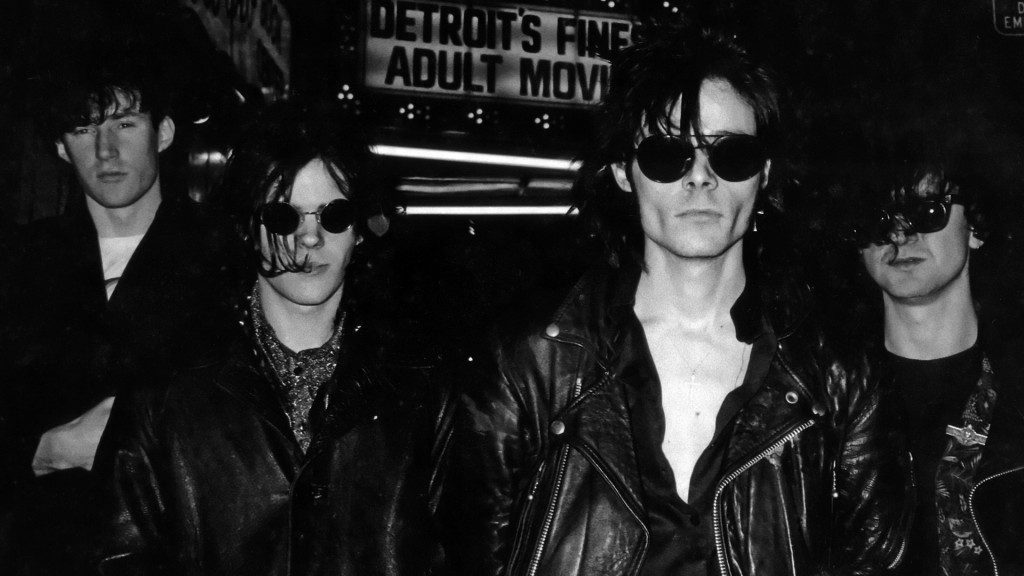

Whilst The Sisters were letting the dry ice part to enjoy increased visibility, The Cult were mounting an all-out assault on the charts. Their debut, Dreamtime, had been a gleaming beast, all gold and bronze shades, telling tales of spirits and the dreamworld. Duffy’s guitar-work was masterful, a melodic take on hard rock with soaring lead-lines bolstered by surprisingly muscular riffs, whilst Astbury’s powerful bellow steered the songs into the mystic. It had made the UK top 20, but the follow-up was about to shatter all expectations.

Wearing their love of psychedelic rock on their sleeves, Love was a masterpiece, a dark and sensual thing, full of hooks, solos, and poetry. Lead single, ‘She Sells Sanctuary’ brought gothic rock smashing into the mainstream, a pop hit built on a coruscating guitar riff that is still a staple of FM radio today. ‘Brother Wolf, Sister Moon’ was a brooding ballad, every inch as magisterial as ‘Riders on the Storm’ by The Doors, while ‘Phoenix’ and ‘Love’ were chaotic jams, solos screaming from the pits of hell.

Clad in leather and paisley shirts, The Cult had left behind the white face-paint of goth, in favour of a pre-punk sensibility. This was music infused with the Satanic majesty of Jimmy Page at his best, the dangerous sexuality of Jim Morrison at his worst. If ‘rock’ was a dirty word, The Cult were revelling in it, and the record buying public had fallen for their charms in a big way. Relentless touring only added to the appeal, and by 1986, Astbury, Duffy, and bassist Jamie Stewart (the band never had a permanent drummer, resulting in a Spinal Tap-esque succession of musicians occupying the stool) bunkered down in The Manor Studio in Oxfordshire to record the follow up. If Love was big, Peace had to be bigger.

The Sisters of Mercy were in a prime position to capitalize on the meteoric rise of The Cult. Andrew Eldritch, whilst in no way as accessible as Astbury, oozed a dark charisma all of his own, and Wayne Hussey’s guitarwork was just as psychedelic as Duffy’s, if slightly less muscular. But as The Cult began to live out their rock and roll fantasies, The Sisters imploded in a spectacular fashion, bickering and feuding in a bust-up that wouldn’t settle for decades.

Guitarist Gary Marx was the first to go, fed up with the polished direction the band were going in. Craving the rawness of The Stooges, Marx split in the midst of a tour, no-longer able to reconcile his vision with that of Eldritch. However, by this point, Hussey was becoming the dominant force in the band, his swirling mesh of guitars giving the Sisters their signature sound. Reconvening to lick their wounds, Eldritch, Hussey, and bassist Craig Adams started work on a new album, to be titled Left on a Mission of Revenge. But the project quickly ground to a halt, and the band split, with Hussey and Adams leaving to form a new band, leaving Andrew Edlritch, the dark lord of gothic rock all on his own, with just a drum machine for company.

Initially, the split was relatively amicable, and with Eldritch maintaining that neither party would capitalise on the band name, both were ideally placed to build on the success they’d enjoyed. When Hussey and Adams named their new band ‘The Sisterhood’, the sparks started to fly.

Eldritch responded by quickly forming a new group, and rush-releasing a single before Hussey and Adams could react. The name of his new band? The Sisterhood.

Things escalated when a single called ‘Serpent’s Kiss’ appeared, credited to The Mission, Hussey and Adams co-opting the title of the abandoned Sisters of Mercy album. Harsh words would be exchanged on both sides, but amidst all this rancour, the songs kept coming out, and the sales kept rising higher.

Whilst Eldritch released an album credited to The Sisterhood, it was obvious that this was a stop-gap, and before long, he’d reverted to The Sisters of Mercy, embarking on a remarkably successful chart assault over the next few years. For his part, Hussey largely discarded the doomy, sonorous brooding of Eldritch, in favour of something more straightforward. The Mission, much like The Cult, openly displayed their love of classic rock. And whilst the music still had the gleaming textures of goth, the songs adhered to a harder template. Brimming with melodrama, The Mission’s initial collection of singles firmly established them as a dynamic, over-the-top rock band, wanting to plant kisses on your spine, before leaving roses on your grave.

Beginning with a portentous opening monologue, (“I still believe in God… but He no longer believes in me…”) God’s Own Medicine was like Love in many respects, but with the pomposity turned up to the max. Bizarrely, for a band that owed its roots to punk, the overwhelming influences were Led Zeppelin, prog rock, and the New Wave dynamics of U2. Critics hated it, but the record easily made the UK top 20, establishing The Mission as a force in their own right. Hitting the road, the band severed all ties with the brooding darkness of The Sisters, living life in a whirlwind of rock and roll excess, enjoying every second of it, and putting a smile on the pouting face of goth. They might have been dolled up in dark, psychedelic garb, but if The Mission were actually on a mission, it was simply to get to the bar before anyone else.

A key track on God’s Own Medicine was ‘Blood Brother’, Hussey’s tribute to Ian Astbury. With his trademark mesh of textured 12 string guitars, Hussey penned an ode to someone he viewed as his soulmate, a partner in crime, bringing rock back into the heart of music. Whilst Astbury had cast himself as a mystic shaman, Hussey viewed both men as warriors in an epic struggle, born from legend.

‘Hubris’ is a word that doesn’t seem appear in Hussey’s vocabulary, and whilst the critical barbs would continue to be thrown at The Mission, they carried on oblivious, creating their own self-mythology to a legion of hardcore fans.

Andrew Eldritch, on the other hand, seemed to care little for what anyone thought, be they critics, industry types, or even fans. Floodland had showcased a radically reinvented Sisters of Mercy, dance-pop dynamics creating towering, epic songs that refuted easy categorisation. ‘This Corrosion’ and ‘Lucretia, my Reflection’ would become dancefloor staples in indie discos for many years to come, despite featuring a gothic choir, the warbled croon of Eldritch, and a deliberate lack of melody. In the videos, Eldritch grew a beard, wore a white suit, and spat in the face of every attempt to pin him down to a particular scene, whilst new recruit Patricia Morrison, formerly of The Gun Club, brooded and pouted, giving the impression she was an equal partner in the band.

But perhaps stung by the departure of Hussey and Adams, Edlritch remained firmly on his own. It’s been disputed how much Patricia Morrison actually played on Floodland, and Eldrtich seemed determined to phase out his human bandmates in favour of machines. The Sisters enjoyed a truly surprising moment in the limelight, with Eldrtich and Morrison becoming unlikely sex symbols for the gothic generation, but it wouldn’t last. By the end of the decade, on his own again, Eldritch re-jigged The Sisters of Mercy for one more crack of the whip. It would turn out to be their last.

In sleepy Oxfordshire, Peace was not going well. Ian Astbury and Billy Duffy appeared to have overreached themselves in their attempt to craft the ultimate rock album, spending months on overdubs and remixes, with precious little emerging from the sessions. With the guts of an album eventually ready for release, they contacted Def Jam supremo Rick Rubin to remix one of the tracks for release as a single. By 1987, under the guiding hand of Rubin, the entire album had been re-recorded, and was released as Electric. And with this, the UK’s biggest gothic rock band cut all ties with the genre, emerging as a heads-down hard rock outfit, full of sex and danger.

The Electric tour was the stuff of legend, with Astbury in particular living in the middle of his own rock and roll circus, repeatedly happy to bite the hand that fed him in his pursuit of infamy. The 1989 follow-up, Sonic Temple, was a guns blazing stadium rock album, with Duffy pulling guitar-shapes on the cover. Tours with Guns ‘N Roses and Metallica cemented their reputation, and The Cult continued their journey to the stratosphere.

Then grunge happened. And overnight, gothic rock was swept away as an unfashionable relic of the past, never to return.

Whilst the reality isn’t quite that cut and dried, the fact of the matter was that grunge quickly established itself as the dominant commercial force in the early 90s, and within a very short space of time, many rock bands –still packing them into gigs and selling plenty of records – were deemed totally uncool. And when rock bands think they’re uncool, they frequently make clumsy attempts to do whatever’s cool. With disastrous results.

The Cult immediately floundered with Ceremony. Released two weeks after Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’, Ceremony was a confused record, with Astbury doing his best to come across as some kind of hip-swaying spiritual guru figure, while Duffy was still caught in stadium rock mode, tearing out some of his most uninspired, yet virtuosic solos, pushing The Cult dangerously close to Bon Jovi territory. A costly legal battle over the use of the cover further sidelined the band, after they used the photo of a Native American girl for the cover without permission. Astbury may have proclaimed that the “funky style music got you good, now children”, but the children didn’t seem to agree with him.

Cutting his hair, and embracing grunge, The Cult (1994) saw the band stripped down to basics. But the problem was that it was someone else’s basics. For the first time, The Cult sounded like they were struggling to keep up, and whilst the taut, sinewy grooves of the album could conceivably have led to a commercial rebirth, it just wasn’t to be. The Cult split in 1995.

With audiences clad in torn denim and plaid shirts, The Mission’s beads and crushed velvets were never going to fare well. As the 80s came to an end, they were in good commercial health, having cultivated a loyal legion of fans though their formidable live show and constant touring. To a far lesser extent than The Cult, The Mission had dropped some of the gothic trappings of their music, even managing to enlist Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones to produce their second album Children in 1988.

As the 90s dawned Wayne Hussey’s self-belief led to The Mission essentially releasing a double album in two parts in the same year. In an unusual move, Hussey threw the tracklisting open to their fans, and through a competition the running order for Carved in Sand (1990) would be chosen by their fanclub. The unused tracks formed the basis of Grains of Sand (1990), but once the dust had settled, it became apparent that there were enough good tracks for one quality album, and spreading it out over two had weakened their impact.

In the post-grunge landscape, The Mission looked in a singularly precarious position. No longer able to command the same levels of devotion they’d become used to in the 80s, Hussey diversified further, releasing Masque in 1992. At a point where it might have been sensible to tap into the sizeable audience who weren’t sold on the raw charms of grunge, Masque found The Mission trying their hand at every genre they could get their hands on, with extremely limited success. Baggy, grunge, AOR, and dance are all tackled, and the resultant mess of a record sank without trace. Neverland (1995) and Blue (1996) did little to halt their commercial decline, and The Mission called it a day in 1996.

By the time The Cult and The Mission decided to give up the ghost, Andrew Eldritch had long retreated into a world of myth. Following Floodland, The Sisters of Mercy had been re-born as a heavy rock band, harder edged guitars replacing the gothic atmosphere of before.

Released in 1990, Vision Thing has a rawness that doesn’t quite anticipate the explosion of grunge, but ably proves that Eldritch knew a change was on the horizon. The guitars focus on bludgeoning riffs rather than atmospheric subtlety, and the pounding drum machine of Doctor Avalanche pushes them towards a sound that was more akin to Nine Inch Nails and Ministry than any of the goth rock bands they’d once been contemporaries of.

Much of this was born from necessity, Vision Thing having had a painful birth. With multiple line-up changes, Eldritch’s original plan had been to deliver East West records the five tracks they’d completed as the finished album, but the label refused to accept it. Three more songs were hastily completed, and Vision Thing was released to critical acclaim and a no.11 placing in the UK album charts, but the seeds had been sown for Eldritch’s withdrawal from music.

Two ‘best of’ compilations emerged, and by 1993, Eldritch announced that he was effectively “on strike” with East West records. The band would never release music again.

In the years that followed, gothic rock became a laughable relic of the past, only mentioned in sneering jabs by critics. Grunge would implode messily, to be replaced by Britpop, and by the early 21st century, popular music was a morass of styles and genres, with none emerging as dominant for too long. That period (1984 – 1990) steadfastly refuses to be rehabilitated, with gothic rock simply resisting any attempt to be revitalised or incorporated into any revival sound. For various reasons, it remains firmly tethered to the past, and seemingly nothing can change that.

However, to varying degrees, all three of the major players have returned to the fore in recent years. Ian Astbury and Billy Duffy have reconciled after an abortive reunion in 2001, and have released three albums that make a strong case for them being hailed as one of the most important rock bands of the 80s and 90s, as well as being a vibrant and forceful contemporary hard rock powerhouse. 2016’s Hidden City finds them revitalised, still defiantly shouting into the power of an oncoming storm.

The Mission kept their fanbase satisfied with posthumous compilations and live releases, before getting back together in 2007, touring and releasing new music. As God’s Own Medicine celebrates its 30th anniversary, the band seem comfortable with their legacy, rightly celebrating it as a glorious moment in UK rock history.

For their part, The Sisters of Mercy never really went away, keeping alive as a touring act. Andrew Eldritch is either unwilling or unable to release new music, but they remain a formidable live band, and audiences still flock to see the swathes of dry ice that shroud their stage show.

And whilst it seems unlikely that any of the bands will ever return to the commercial success they once enjoyed, their place in history seems to be secure. ‘Goth’ isn’t the dirty word it once was, and with the rise of music streaming and YouTube, audiences are free to discover this forgotten era of British rock without the stigma that has clung to it for so long. Celebrating darkness, romance, sex and sensuality, and rocking hard in the face of prevailing trends, maybe the time has come for gothic rock to step back into the light. Steven Rainey