One of the more interesting quirks of our society, as it moves through the ages, is the re-emergence of patterns that we often mistake as being innovative simply because they did not initially emerge during our lifetime. Fashion notoriously produces examples of this each and every season. The cultural polymath is another example of a re-emerging pattern disguised as a new facet. He or she is a photographer/artist/filmmaker – and it is not unusual to view a business card inundated with slashes to highlight this. While this may seem as a new trend, a short glance back in history reveals that the expectation that an artist should choose a single path to invest their energies in is a relatively new concept. In particular artists in the 19th Century seemed to have an aversion to the concept of expression through a singular medium; Dadaists, surrealists, and symbolists were defined as much by their versatility as their oeuvre. They viewed each medium as being under the banner of artistic expression and refused to restrict themselves to just one. In this way, High Winds Move Slowly is an exhibition of two artists hailing from this classic tradition.

High Winds Move Slowly, in Sligo’s The Model, features the works of two Dutch artists – Arno Kramer and Henk Visch. Kramer has established himself as a versatile artist, working as a visual artist, curator and poet; while Visch has developed a reputation as a sculptor, draughtsman and graphic artist. In this show, Visch presents work which expresses human suffering through his disembodied, humanoid sculptures, while Kramer favors escapism into an otherworldly animal realm of his own creation. The intertwining of these artists creates an arresting visual language that tackles alienation, suffering, coping and the nature of life itself.

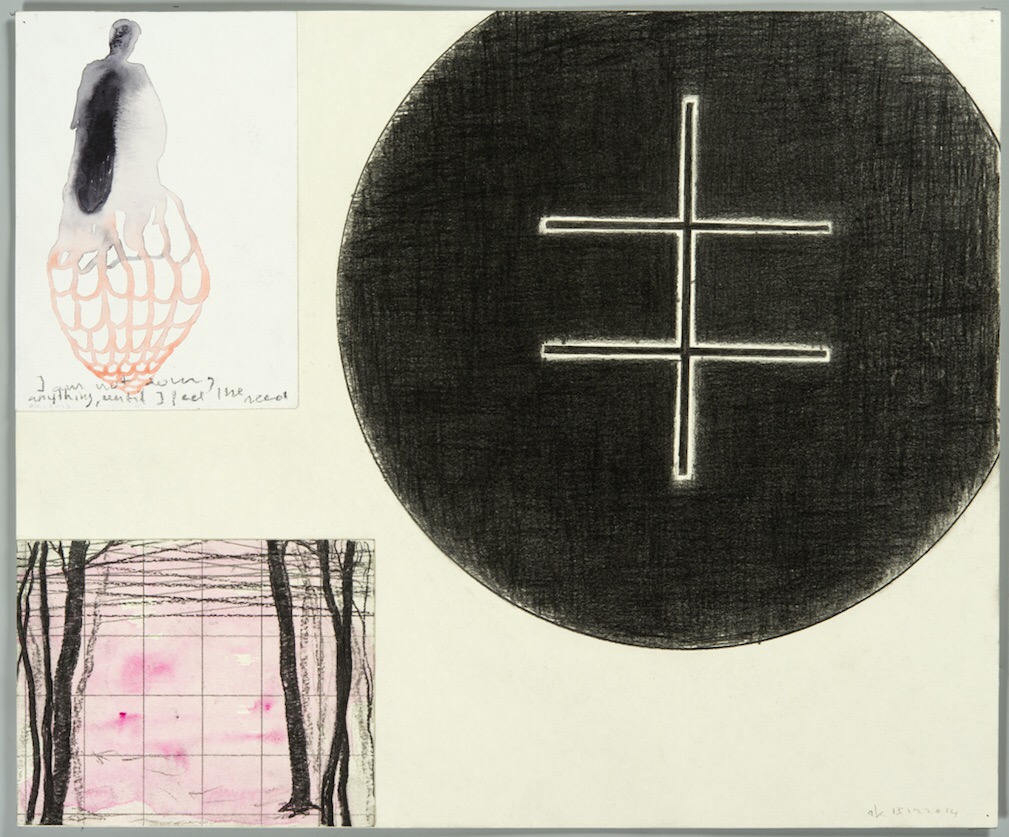

Colossal snapshots of Kramer’s world hang on the surrounding walls while Visch’s colourful sculptures are interspersed throughout, ushering the viewer closer to the potent meaning that binds these two artists. Their disparities create a certain tension that enriches the exhibition and enhances the viewing. Kramer for example, leaves many of his works untitled. Some are gifted names with great philosophical significance in either English or German. These bare the influence of Kramer’s poetry, which sometimes takes the form of the written word, while on other occasions the artist express it exclusively through a visual language.

Visch, in contrast, views his titles as fundamental tools in understanding his sculptures. In the artist’s work titles hold the same significance as names hold to humans. They are the first nod towards his initial intent, a gentle nudge in the right direction – although they do not necessarily indicate an obvious meaning, and in some cases they do the opposite. An illustration of this latter technique can be found in the concluding room of the exhibition. Located in the center of the space is a large sculpture, resembling a coiled, metal spring. The title of the piece is The Stage, and one which points to a certain sarcastic wit as a sharp metal coiled spring would be an incredibly inhospitable stage for any performer. The audience could speculate that this is Visch’s commentary on the nature of infamy in the world of contemporary art.

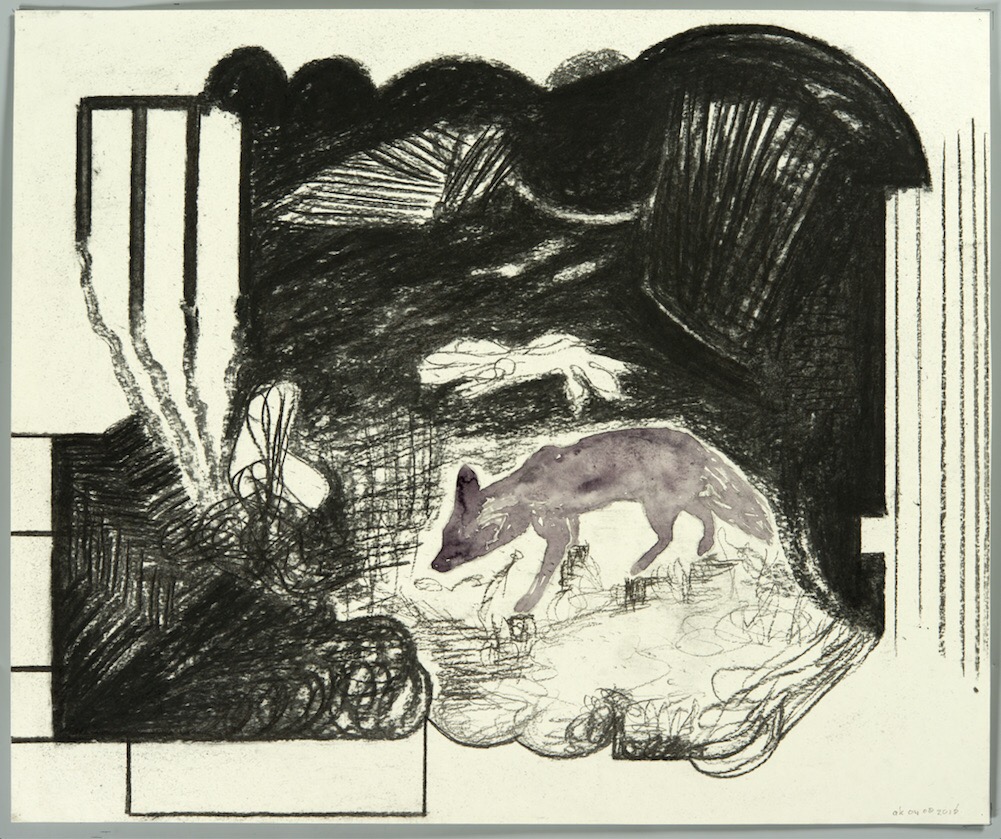

Kramer works on an extremely large scale, epitomised by the bespoke mural created for the gallery’s atrium. The mural, which is untitled, dominates over the space and acts as a portal to the highly sensitive world of animals and the occasional man. Here Kramer utilises watercolor and charcoal to design his mini-verse, that sees him contrast between definitive sharp willow lines that slash through his canvas. While his animals, captured in a moment of perpetual motion, bleed vitality and life. The relationship between these two elements references man’s trespass and destruction of the animal kingdom. This sentiment is echoed throughout the exhibition’s gallery spaces. The animals, that range from hares to wolves, seem to be devoured by the black, encompassing shadow lines. Man is represented again and again as a figure of violence, encroaching and violating into a world in which he no longer has a place

By contrasting his lively animals with the cannibalistic chaos of their environment, Kramer has created an unsentimental yet ethereal world. With the ghostly hue of charcoal, Kramer designs animals that neither hide, nor confront the audience. It is as if one has acquired the power to see into another realm, one that lies beyond our physical dimension. Perhaps into this pursuit, the artist has inadvertently bonded his poetic outlook and his artistic skills to create a visual language for poetry. For a viewer, beholding the visceral power of High Winds Move Slowly this mural is in essence: an other-worldly experience.

If Kramer is an escapist then Visch works on the opposite end of the spectrum. His role as an artist is one of a translator, propelling his beliefs into the meaning of existence and bringing them forth into the world via his sculptures. His creations are never quite whole. They are mutilated, often missing limbs. Yet they are painted in vibrant hues, their disembodiment coated in glaring greens and blood reds. This use of colour is brings to mind the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat. This pairing of form and colour is in direct subversion the viewer’s expectation. He creates sculptures that have misery in their very aura, but then coats them in layers of sugar paint till they pop with potent colour. In The artist in love, a humanoid statue whose arms are non-existent, a figure is bent at the shoulders, hanging it’s head in shame. Like many of Visch’s creations, she is in a state of perpetual discomfort, yet it’s hue is a vibrant, cheerful green.

The less Visch’s sculptures tend to resemble humans, the more likely they are to display outwardly positive emotion. With Enemies of the third dimension (Charlotte) & (Moritz) we see angular, robust sculptures which are extremely abstract despite their humanoid forms. The welding of metal lines and spirals renders them into a couple, one large, the other not so. There is something almost touching about this pair, the larger seems to project an air of paternal protection while the smaller is positioned slightly behind, like a cowering child. There are a number of intriguing elements to Visch’s work. His sculptures tend to display little in the way of facial expression, with many of his large scale pieces, like Subterranean Man, glare at their audience with a blank, hollow gaze. This lack of expression that he asserts upon his sculptures provides an opportunity for his audience to ponder them further.

The absence of horror in Visch’s sculptures and their seeming unawareness regarding their mutilations is symbolic of the emotional mutilations that subconsciously burden all of us. These disturbing emotions, violent tendencies and traumatic memories, though buried deep within our psyches, dictate our conscious everyday lives. They reign over us, choreographing even our most menials of interactions to the stark decisions that shape our lives. It is this thread that intertwines both Visch and Kramer. An echo of these repressed thoughts is apparent in Kramer’s work, where the presence of man is suggested through images of violence. Man, like repressed thoughts, is an unwelcome intruder in the dark, encroaching in this mystic world of flora and fauna.

High Winds Move Slowly is a visually striking exhibition but it’s true power lies in its intent of it’s creators. Both artists possess feelings of alienation towards the rest of humanity. Kramer’s dark animal kingdom presents mankind as a violent destroyer of purity and the natural world. Visch’s sculptures inform us that to be human, is to suffer. While some exhibitions seek to instill meaning in its audience from the moment they pass the threshold, High Winds Move Slowly is a slow-burner. It’s an expression that asks you not to hastily formulate a response immediately but to think and contemplate. Wander through the brightly lit galleries and contemplate the nature of society, the modern world and your place within it.

Written by Rebecca Kennedy

High Winds Move Slowly continue in The Model until November 12th

Images courtesy of The Model and Heike Thiele