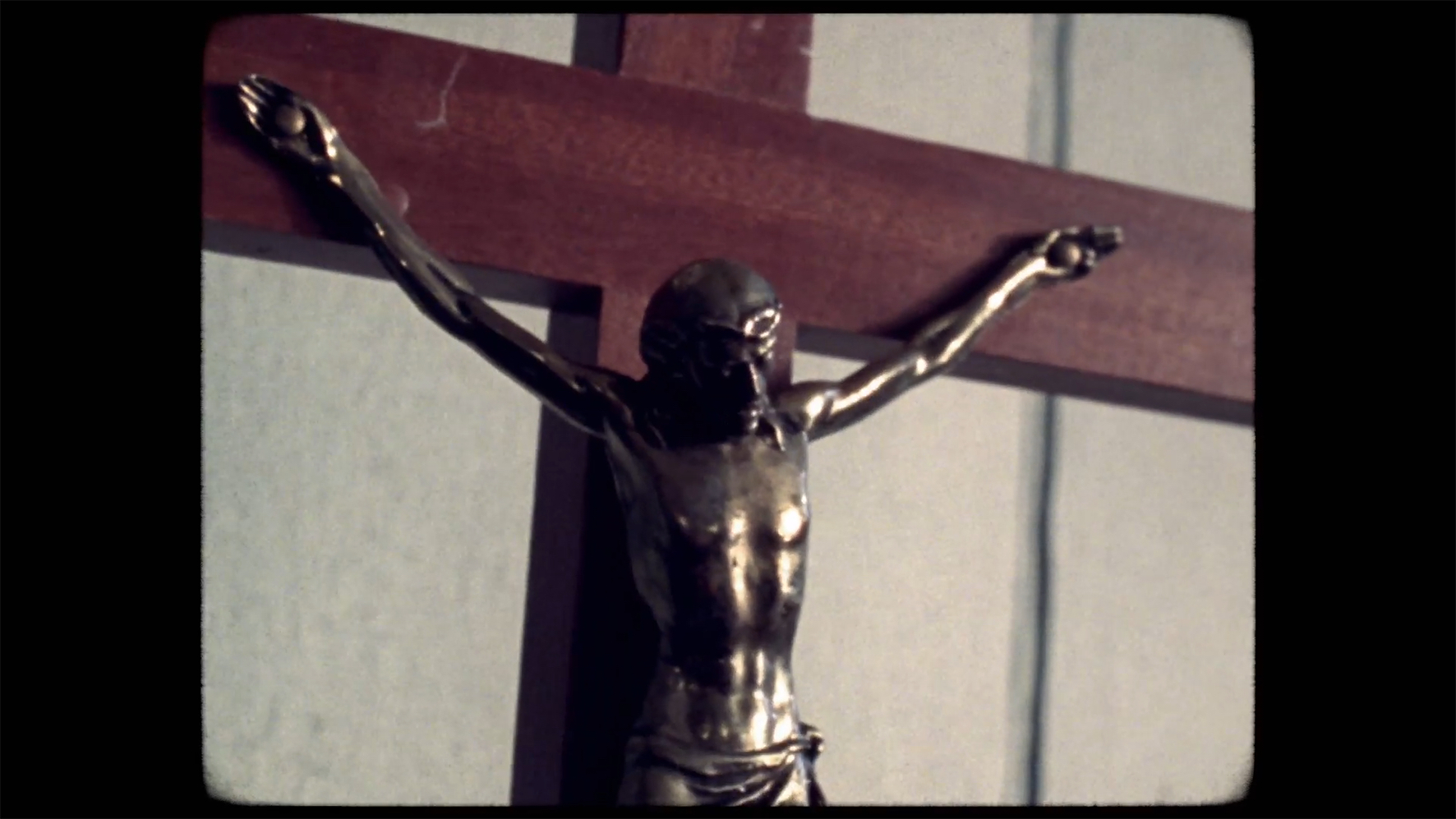

A pregnant woman in chains; the off-screen wailing of child spirits; close-ups of the Virgin Mary with lines of blood down her cheeks, weeping at the sights she sees. The Devil’s Doorway, a Northern Irish horror which last week screened in the Galway Film Fleadh, and received American release through IFC Midnight, is an efficient frightener with local colour and a dense, tight atmosphere of suffering, penance and punishment. You might call it Catholic guilt.

The debut film from Belfast writer and director Aislinn Clarke, who lectures in Creative Writing at Queen’s University, and the first NI Screen-backed feature from a female film-maker, The Devil’s Doorway is a found-footage horror that turns its gaze upon one of the shrouded alcoves of Irish historical shame, following two priests dispatched to a ‘Magdalene Laundry’ in 1960 to investigate possibly miraculous activity.

The Laundries, astonishing asylums for vulnerable women of all types, justified via the sin logic of ‘fallen women’ whose souls needed saved and the economic usefulness of their forced labour, remain sites of cloudy profanity. Even as the Irish State has taken steps to formally acknowledge, and apologise for, their essential injustice, trauma lingers in the survivors, and their ordeal demands story-telling excoriation beyond Peter Mullan’s well-known 2002 drama The Magdalene Sisters. Clarke’s film is a welcome genre intervention.

Father Thomas (played by Lalor Roddy) has the doubt of his namesake; older, more skeptical, weathered by a lifetime in institutional religious pragmatism, he’s reluctant to assign supernatural rationale for Our Lady’s tears. Thomas is the voice of conscience, a wish-fulfilment challenger to the mini-tyrannies of the country’s Mother Superiors. Manning the camera, and its flickering bulb, is Father John (Ciaran Flynn), younger, enthusiastic, eager to believe. Almost as soon as the men arrive at the Laundry the freaky-deaky begins; coming in at a sparse 76 minutes, The Devil’s Doorway settles quickly into its creep.

The last handful of years have seen a number of horror movies informed by, or located in, Irish realities. Some, like The Hallow, Without Name, or Wake Wood, transform lush rural landscapes into a hostile force; others, like The Cured or Let Us Prey, stick closer to marketable sub-genres.

Among this rash of Celtic chillers, The Devil’s Doorway stands out for its texture and resonance, using the found-footage logic of dis/recovery to dive into real-life atrocity, and, in Roddy’s performance, finding a moral counterweight to the genre jump-scares and ‘possession’ regulars of spinning crosses and crooked bodies. Clarke sidesteps the cheesiness and cheapness that often come with found-footage, first, with the retro cache of 16mm film, recreating the spotted, clicking reels and that claustrophobic, intimate ratio and, second, with the urgency of its politics, expressed in witty, accusatory dialogue asides.

When the Fathers end up in the Order’s subterranean chambers and their shoes crunch on child-sized remains, the mass graves jump to mind, prompting shivers of a higher timbre. In its conclusion the film gestures to Rosemary’s Baby, and, at a stretch, this year’s Hereditary, in its invocation of an evil extraordinary in the sense that it is indeed extra-ordinary, a genteel conspiracy by the respectables of church and state. Helena Bereen (Hunger, Made in Belfast) is crucial here, convincing as the Mother Superior, her stone-faced condescension hiding all sorts of dirty laundry. Conor Smyth

The Devil’s Doorway is available on American VOD platforms. It will receive an Irish/UK release soon. Read our interview with writer/director Aislinn Clarke here.