Neil Hannon has always been, rather consciously, something of an anachronism in contemporary pop – an urbane, arch throwback to suave crooners and irreverent singer-songwriters of the 1960s. In a way, this made sense in the ’90s, when The Divine Comedy were at their commercial height. After all, Britpop juggernauts Oasis and Blur were fetishists of the ’60s, lifting the Beatles’ and Kinks’ aesthetics from the middle part of that decade; Jarvis Cocker, when not drawing inspiration from Serge Gainsbourg, shared Hannon’s obsession with the wry, literary Scott Walker. But while Albarn and Cocker combined those influences with more contemporary sensibilities, Hannon was a purist – faithful to the sophisticated baroque-pop of his heroes, and enthralled by the period’s fashions and cultural ephemera.

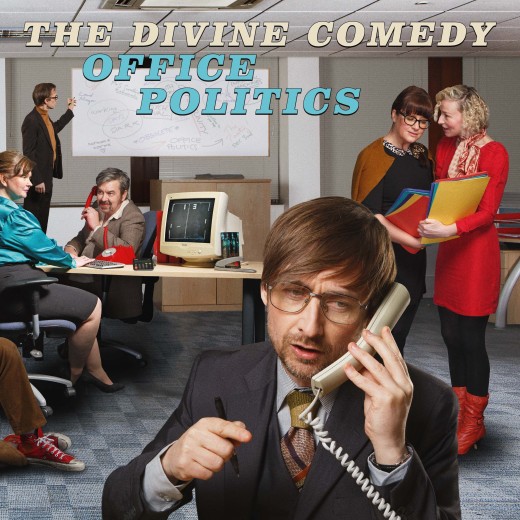

Perhaps it’s little surprise, then, that Hannon feels “at sea in modern society”, as he told The Irish Times recently. Those paying attention may have thought as much for some time – 1998’s otherwise stellar Fin de Siècle opens with an overwrought and preachy number called ‘Generation Sex’, and his most sensitive character studies often appear to lament contemporary mores (see: ‘Our Mutual Friend’, ‘Becoming More Like Alfie’). Unexpected, however, are the sonic departures made on Office Politics, The Divine Comedy’s twelfth record. The double album (another anachronism?) is partly influenced by the new wave and synth-pop of the late ’70s and early ’80s; here, references to the period’s stark, minimal electronics soundtrack Hannon’s bleak musings on the depersonalising effects of technology and modern work life. The songs’ central characters, Hannon has said, are the machines.

Unfortunately, the record’s engagement with this theme is rather unfocused. Amid songs that either furnish Hannon’s typical tunefulness with tasteful electronic flourishes, such as new single ‘Norman and Norma’, or find him navigating his usual sonic terrain, as on the elegantly arranged final tracks ‘After the Lord Mayor’s Show’ and ‘When the Working Day is Done’, there are several songs that amount to – at best – failed experiments. Hannon has explained that his decision to make a double LP was informed by a desire to retain some of the “weirdness” that typically ends up on the cutting room floor as his albums are recorded – but when the ideas are as half-baked as some of those found here, one wishes he’d instead retained the instinct for judicious editing.

At its worst, the record curiously resembles the ’80s nadir of Sparks; as with the Brothers Mael then, Hannon appears to have acquired the notion that synth-pop is an acceptable canvas for depthless lyrical conceits. Rinky-dink electronics back one-note jokes on tracks like ‘The Synthesiser Service Centre Super Summer Sale’ and ‘Psychological Evaluation’, while ‘Infernal Machines’ rages impotently (and irritatingly) against the prospect of automation. Elsewhere, on relatively standard musical fare for Hannon, these lyrical concerns are expressed in creaky fashion (“You’re living in a prison of your own design / That crazy algorithm’s making up your mind”), as though he were writing poetry to “wake the sheeple” on his Facebook feed.

Hannon excels at crafting thoughtful character studies with short-form pop songwriting, and when complemented by the refined musical settings that usually populate his records – many of which may appear conservative initially, but are regularly playful and eccentric – they can assume a strange profundity, as moving as they might be jocular or ironic. The aforementioned ‘Norman and Norma’ satisfyingly depicts a suburban marriage in three acts, while also seemingly evoking vintage sitcom theme tunes; the result is as much a tender reflection on age and romance as it is a comic vignette of middle-class banality. ‘I’m a Stranger Here’, meanwhile, recalls its author’s comment about modern alienation (“I’m a stowaway from the olden days”) as its lilting rhythm, meandering brass, and stately strings convey some acknowledgment that the song’s outlook is faintly ridiculous.

It’s a pity that these fine moments are undercut by Hannon’s feeble experiments with his new (old) toys, crap puns (the risible “Opportunity’ Knox’), and song-length gags (‘Philip and Steve’s Furniture Removal Company’, a joke explained at its beginning and then repeated for almost five minutes). By the time listeners arrive at the two superb final tracks, far more flattering showcases for Hannon’s wit and stylish melodic sensibilities, they might feel they’re being rewarded for some pointless exercise in masochism. A misfire, considering Hannon’s typically sharp instincts. Seán Kennedy