“Whether you experience heaven or hell, remember that it is your mind which creates them.”

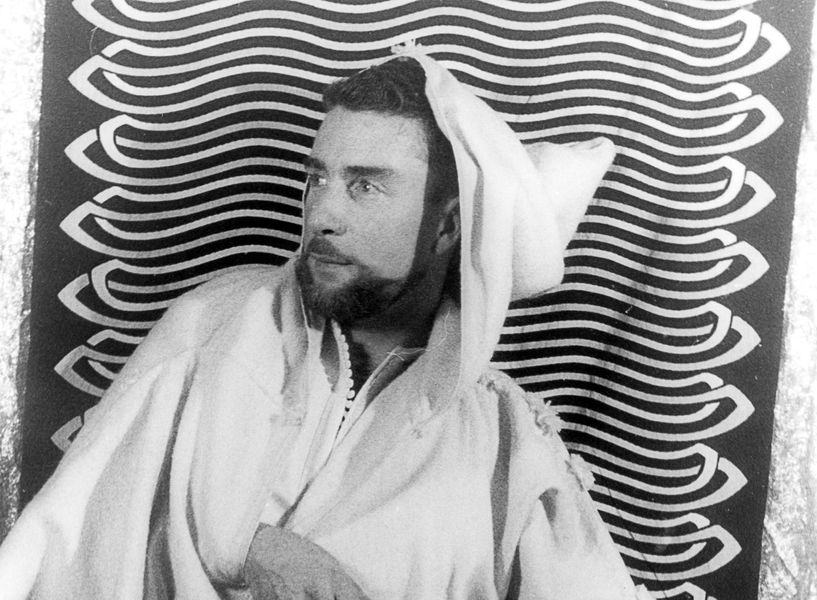

Six years before Timothy Leary wrote these words in his seminal 1966 text, The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, Brion Gysin quite literally saw the light. On a bus journey to Marseille, the British-Canadian artist-inventor had an encounter that could be described as a pretty textbook psychedelic experience — one without the aid of psychotropic drugs, foundational Tibetan guides or anything in between.

As the setting sun cut through rapidly-passing trees, Gysin shut his eyes before observing what he called “a transcendental storm of color visions.” He noted an “overwhelming flood of intensely bright patterns in supernatural colours exploded behind my eyelids: a multidimensional kaleidoscope whirling out through space. I was swept out of time. I was out in a world of infinite numbers. The vision stopped abruptly as we left the trees.”

Without question — without trying — Gysin’s mind had, in a Learyian sense, created heaven.

At the time a resident of the Beat Hotel in Paris, and a pioneer of the cut-up technique alongside his close friend William Burroughs, Gysin was so struck by the experience that he quickly got to work on creating a device that he hoped would approximate what he had felt. Teaming up with Burroughs’ “systems adviser,” the electronics technician and computer programmer Ian Sommerville, he cut holes in a cylinder, inserted a 100w lightbulb in the center and placed it on a 78rpm turntable. Just like that, the Dreamachine was born.

There was nothing to it: a person, or persons, would sit in front of it and shut their eyes. Flickering — or stroboscopic — light would stimulate the optic nerve and alter the brain’s electrical oscillations. This, in turn, would produce visions of bright, moving and steadily warping colours in geometrical patterns, seemingly projected behind one’s eyelids.

Unveiled in 1962 at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, Gysin’s vision for the Dreamachine as an art object that would supersede television has not yet come to pass. But such a fact neglects the seismic impact that it, and its creator, had on various artistic and philosophical circles of the ’60s, ’70s and beyond. In a letter to Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg wrote: “I looked into it–it sets up optical fields as religious and mandalic as the hallucinogenic drugs–literally… (look in with eyes closed) – it’s like being able to have jeweled biblical designs and landscapes without taking chemicals. Amazing. It works.”

In 1989, Leary himself noted: “[Gysin] was one of these very seminal figures. The Dream Machine is a very early, wonderfully creative and primitive psychedelic machine.”

Vast swathes of reality have come and gone since the consciousness exploration of the 1960s, in which Gysin played a leading, though somewhat overlooked role. Now, two generations on, his high hopes for the Dreamachine are finally being realised thanks to a groundbreaking immersive experience of the same name. Created by Collective Act, alongside Turner Prize-winning artists Assemble, electronic auteur Jon Hopkins, and technologists, scientists and philosophers, it’s presented as part of UNBOXED, a self-described “once-in-a-lifetime celebration” of UK creativity. Following sold-out shows in London and Cardiff, Belfast’s turn at hosting offers a new vantage point to grasp its profound appeal and radical potential.

You don’t need to be a seasoned psychonaut to know that “set and setting” is, when the right time comes, everything. Though shorthand for conditions traditionally conducive to a chemically-enhanced trip, the rationale (a positive and balanced inner & outer environment) is simple, i.e. based in a deep-rooted human desire to feel safe when venturing beyond. Stepping into the sanctuary of the striking, red-carpeted Carlisle Memorial Church, Dreamachine excels in this realm right away. Beaming volunteers helpfully hover and a muted reverence holds sway. One participant, fresh from the (wholly non-chemically-enhanced) experience offers his verdict: “It was psychedelic, so it was.” He may have just traversed the limits of his mind but he most certainly returned back to Belfast.

Sure enough, our friend wasn’t wrong. Following some preliminary chat, kicking back on beanbags on the altar of the deconsecrated Carlisle Memorial, myself and three others are invited to step into an almost pitch-black room. “A blanket and an eyemask*.” Like a long-haul flight. Are we in the Dreamachine, or are we about to experience the Dreamachine? Is this the inner or the outer? No matter: turn off your mind, relax and float downstream. But how? Led by a guide, we are asked to get comfortable — and it’s extremely comfortable — close our eyes, and ease in via a few breathing exercises. A trial run. “Are we all happy to proceed?” We are. A scopic drone by Jon Hopkins fills the room. As pulses of white light dance on the screen of shut eyes, whirling, polychromatic fractals yield to a grid of emerald green. The birth of the known universe soon emerges from a luminous abyss, naturally.

“It’s Monday morning,” I think, stifling a laugh. Back in. No thoughts but Brion Gysin’s words from 60 years previous: “You are the artist when you approach the Dreamachine with your eyes closed,” he said. “What the Dreamachine incites you to see is yours… your own.”

* offered in case a participant wishes to bow out of the experience. Participants are also free to leave at any time

Like all experiences that could be reasonably deemed “psychedelic,” Dreamachine renders language virtually obsolete. What Czechoslovakian psychiatrist & consciousness explorer Stanislov Grof called the “cartography of inner space” almost always wins out over our need to make sense of what we can’t quite fully know. It stands to reason that within the visual cortex, we are creative directors, not linguists or orators. It’s the mind’s eye of the beholder, not their effort or intention, that does the mystical legwork. Ram Dass would have a field day.

Emerging from the Dreamachine after an eternity (20-odd minutes), I sit at a roundtable-of-sorts where conversation, drawing and written testimonies are encouraged but not required. Slowly, it dawns on me that finding out for oneself is truly what it’s all about. Here, participants are guided, not directed. There are absolutely no absolutes – no grand manifestoes, moral frameworks or metaphysical must-knows. Bliss, or this bliss at least, is “just” alpha waves synced to a masterful soundtrack. For me, this distinction — of it being a heuristic experience rather than a didactic one — feels important. By legitimaising the inner value of a free, safe and total legal “trip,” while democratising (if not slightly demystifying) the psychedelic experience, Collective Act and co. go above and beyond in honouring Gysin’s vision. There will be no cosmic gatekeeping here, thank you very much.

Before leaving Carlisle Memorial Church, I grab a few minutes with art producer and Collective Act director, Jennifer Crook. She reveals to me how, when she was a 17-year-old captivated by Gysin’s work, she created a homemade Dreamachine based on his prototype. Years later, at a Jon Hopkins show at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 2014, she had an epiphany: with like-minded collaborators on board, it could be reborn as a scaled-up, full-blown reality fit for public consumption. Eight years on, to call the execution of that epiphany a multi-faceted feat would be doing it a disservice. Guided by her clearly unwavering belief in its simple, transformative power – and bolstered, not least, by Assemble’s exceptional attention to detail in creating a wonderfully holistic physical experience – it feels like a major triumph within a much bigger, pan-generational pursuit.

Having won the backing of all four national governments of the United Kingdom, Dreamachine clearly taps into a hunger for access to a kind of everyday transcendence that, perhaps beyond certain forms of meditation, simply isn’t readily, safely and legally available in public life in the UK. With enough exposure and continued support, I’m convinced it has untold potential in being scaled up and rolled out to help combat any number of deep-set socio-cultural crises, from addiction and substance abuse, to mental illness and – not least here in Northern Ireland – the tight, often unseen grip of generational trauma. It may be another 60 years away, or it could be next year, but the stage is well and truly set. Back in the here and now, one thing rings true: it was indeed psychedelic, so it was. Brian Coney

Sign up to experience Dreamachine in Belfast for free here