“What, uh, do we believe, sir?” a young Richard Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld’s aide during the Nixon years, asks his boss.

Rumsfeld, played by Steve Carell, laughs hysterically, blindsided by the naivety of the question. Matters of personal principles and ideology simply do not factor into Washington power games. It’s a central concern in Vice, the latest in Anchorman director Adam McKay’s swerve from knockabout man-boy comedy to polemical film-making, but it’s also a question the film desperately needed to ask itself. What does McKay believe? What moral vision is he trying to put on screen? What on earth is Vice actually trying to do?

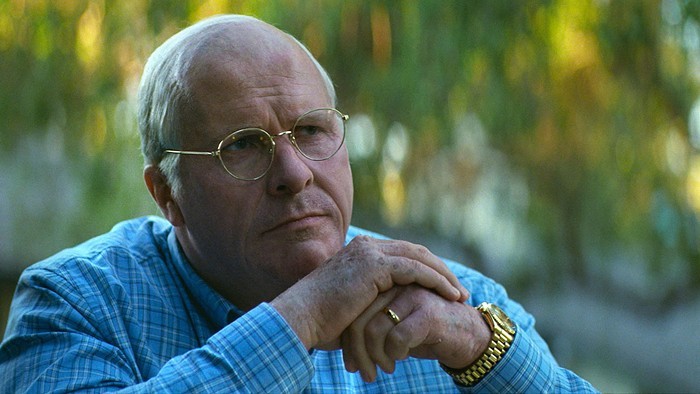

There is an essential hollowness to Vice. Part of this is an intentional exercise in anti-charisma: chronicling the rise of Dick Cheney (Christian Bale) from college dropout party boy to the de facto presidential authority of the Bush Jr. terms, Vice is a character portrait without the character. Spitting snarling asides from a rotund jawline, Bale plays an ethically blank servant to power, waddling through the corridors of American power like a political Penguin. The guiding principle of Dick and his wife Lynne (Amy Adams, the only one actually bringing some emotion) is the accumulation and defence of power and status. The practical results outcomes for the people actually being governed, at home and abroad, are afterthoughts.

What Vice gets right is the mundanity and boringness of how evil operates in much of the modern world. What it gets wrong is pretty much everything else.

McKay used to make smart dumb films. Now he makes dumb smart ones. The director’s insistence on distance from his subject signals a lack of authorial courage. At various points the film emphasizes the basic unknowability of the moments its trying to recreate, which comes off less like clever meta, and more like a throwing up of hands. While the towers were falling down on CNN, why was the VP talking to his lawyer? I don’t know McKay — you’re the one telling the story here.

Later, we join the Cheneys at home, after he’s received the call to be running mate for Bush (Sam Rockwell nailing Dubya’s twinkly emptiness). Lynne warns against it — VP is a “nothing job” — but Dick’s cogs are turning. Again, the narrator (Jesse Plemons) flags up how we can’t know what’s happening in his head, before husband and wife unfurl all their feelings in colourful Shakespearean verse. Real people don’t talk like that, the narrator reminds the audience with a smirk. McKay can’t know what they were thinking, fair enough. But he should at least try something.

Part panto recreation, The Big Short with less fizz, part Vox Explained episode on the modern American right, Vice gets high on its own supply, too sure of its snarky, bitty takes to make points that are compelling or novel. McKay comes across like an undergraduate who has just discovered Michael Moore and can’t wait to tell everyone he meets about how Halliburton stock soared after the Iraq war. The film asks us to get angry about things like extraordinary rendition, Guantanamo Bay and post-9/11 surveillance, but we already got outraged about this stuff, ten years ago.

McKay’s film feels like a time capsule from a time when pretzel jokes were provocative late night material. A shallow, everything-is-fucked final montage tries to suggest connections between Cheney and co.’s machinations and the ills of climate change, refugees etc. but the current political moment is so delicate, so unhinged, that it demands something more substantial than “they lied about WMDs”. Anything else is just dicking around. Conor Smyth

Vice is out on wide release from Friday 25th January.