“Nothing. But was that not something?”

A stage adaptation of Samuel Beckett’s novel Watt is a fairly mad endeavour. Dense, absurd and peppered with extraordinarily long lists of the possible permutations of ordinary events – comings and goings, goings and comings – Watt is perhaps Beckett’s least celebrated novel. Yet this bleak tale of a non-descript man in domestic service for an indeterminate number of years to Mr. Knott, whom Watt learns nothing about, is laced with wonderfully absurdist humour. It is this comic seam, essentially, that Barry McGovern mines in this one-hour, one-man tour de force, on Dun Laoghaire’s Pavilion Theatre stage.

There is no room in an hour for McGovern to fully embrace the unravelling of Watt’s mind, which manifests itself in the novel as a pointless invented language of, nevertheless, mathematical logic, and his entry into an asylum for the insane. The fragility of Watt’s mind, however, is hinted at early in this performance. There are voices in Watt’s ear, voices singing, stating crying, murmuring, others too, ‘and sometimes Watt understood all, and sometimes he understood much and sometimes he understood little and sometimes he understood nothing, as now.’

Watt wears a boot and a shoe, ‘happily of the same brown color’. The boot was the ‘unique remaining marketable asset’ of a one-legged man, who sold it to Watt for eightpence. Watt walk is a ludicrous ‘funambulistic stagger’, his arms dangling by his sides. Not one given to smiling much, there are two things that Watt particularly dislikes. The sun and the moon.

One of Beckett’s most painstakingly absurdist creations, Watt was written, for the most part, between 1943 and 1944 in the remote village of Roussillon, in south-eastern France. For two years, Beckett and life-long partner Suzanne Déchevaux-Dumesnil hid there from the Nazis, aiding the French Resistance by stashing arms. Beckett would suffer a mental breakdown and later described the process of Watt as his daily therapy – a means of keeping himself sane.

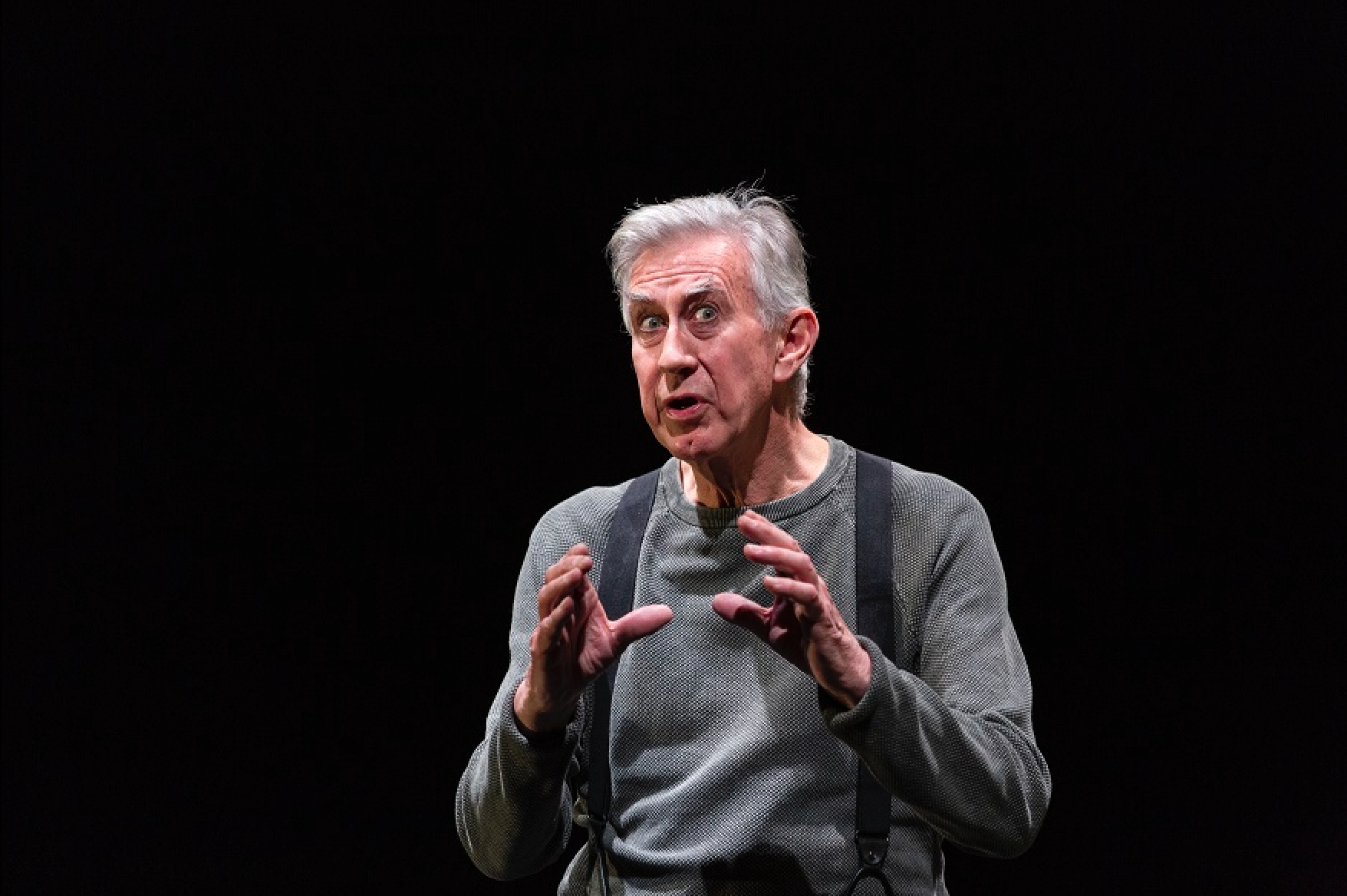

And in the hands of McGovern, this veteran interpreter of Beckett, Watt is damned good medicine. It’s a remarkable performance from McGovern, who channels the rhythms of Beckett’s language so fluently. A widening of the eyes or a raising of the eyebrows is enough to raise laughter, but it’s the flowing contours of the words that hypnotise so, and McGovern’s exquisite comic timing that delights. With Beckett, rhythm is everything and McGovern reads the music better than most.

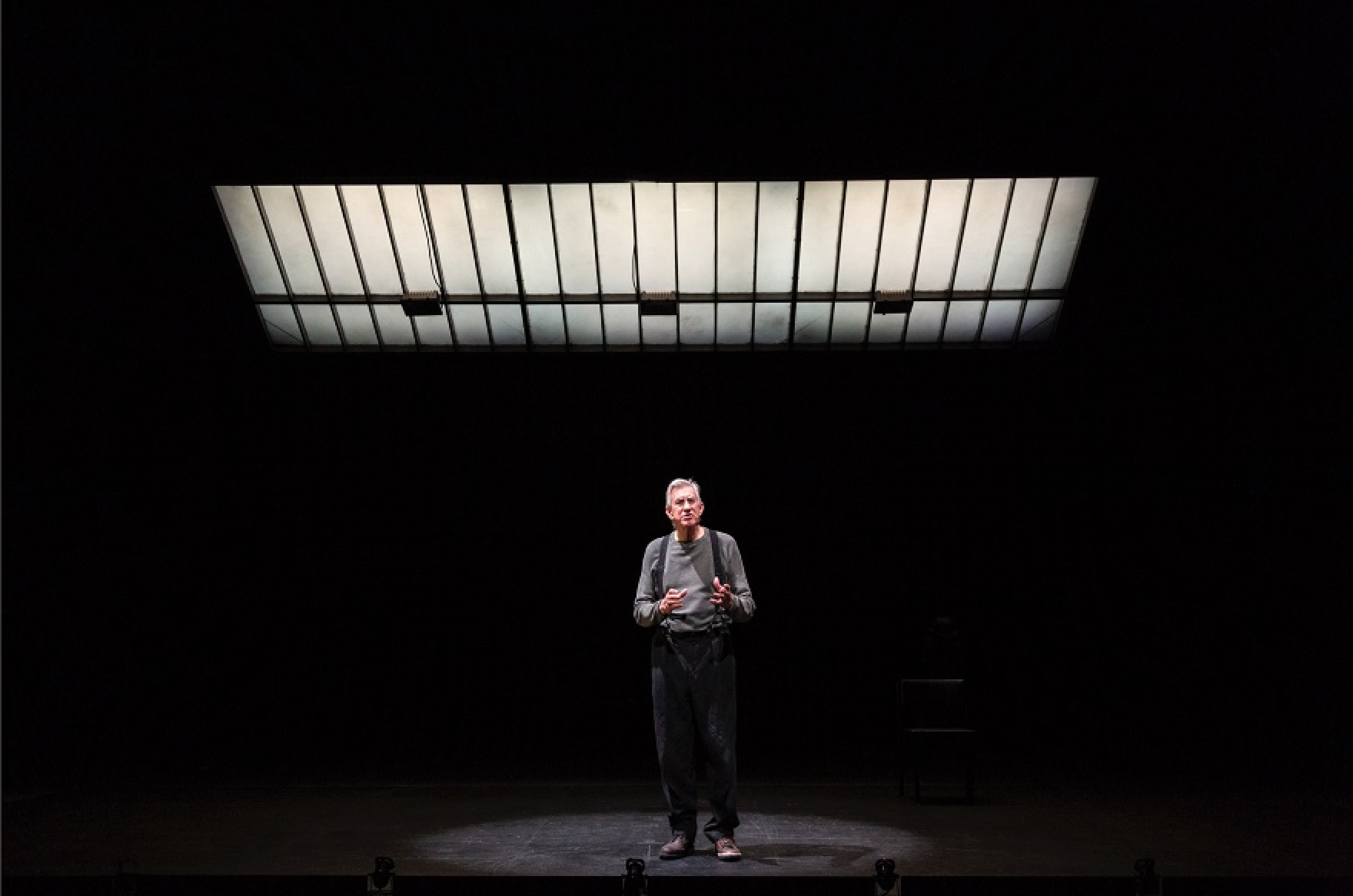

Directed by Tom Creed, though you suspect McGovern needed little directing, most of the novel’s Joycean complexity has been removed, making for a lean, well-paced piece of theatre. And with a minimalist set and lighting design by Sinéad McKenna, all the focus in on McGovern, who holds the audience rapt as he narrates the story of the eccentric, though harmless Watt and his time working for Mr. Knott.

In Mr. Knott’s house others have come before Watt, Walter, Erskine and Vincent, and others will come after. The days are a never-ending cycle of repetitious tasks. Mr. Knott is a reclusive figure. He sees no-one and hears from no-one. In fact, the visit of a father and son team to tune the piano was ‘the principal incident of Watt’s early days in Mr. Knott’s house.’

Mr. Knott’s left-over food is to be given to the dog, except there is no dog. A large, needy family with a famished dog, and in the event of its death, a succession of dogs, has to be found. The sprawling, ailment-afflicted Lynch family fits the bill, of whom the twin dwarves Art and Con lead the family dog to Mr. Knott’s door every day. For a quarter of a century. First, the oddly named bitch Kate, then, when she expires, Cis. Watt never knew how long he spent in Mr. Knott’s service, on the ground floor, then on the first floor. It seemed a long time.

Watt was Beckett’s last work written in English before he switched to French, and whilst the universality of his most famous works invited translation, it’s hard to imagine Watt in any other accent than an Irish one. The habit of Mr. Knott’s gardener, Graves, to pronounce third as turd and fourth as fart would be unhappily lost in translation. ‘Tis only me turd or fart’, he says of his moderate drinking.

The best day for Watt was Thursday, when Mrs. Gorman the fishwoman called. Watt would open a bottle of stout in the kitchen and he would sit on her or she would sit on him. Watt would rest his head on her right breast – ‘her left breast having been unhappily removed in the heat of a surgical operation’ – and forget his troubles for ten minutes.

In the end, however, it all amounts to nothing. Watt realizes that he knows nothing of Mr. Knott. He has learned nothing. Of Watt’s desire to improve, to understand, to get well, there remains nothing. The arrival of Micks one day signals the departure of Watt.

Watt, two small bags in hand, makes his way to the train station where has asks for a ticket to the end of the line. ‘Which end?’ asks the station master. Watt replies, ‘The further end.’ It’s a slight variation from the end of the novel, where Watt first requests a ticket to the nearer end before changing his mind and opting for the further end, in what was almost a foreshadowing of the famous line ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on’ from The Unnamable. McGovern’s truncated adaptation of this scene for the stage is perhaps the one odd editorial call of the show.

The illusion of time, repetition, comings and goings, nothing very much happening, small events magnified, the absurdity of existence, the futility of it all and yet the spirit to endure – all the themes that course through Watt would later surface in Waiting for Godot. In a sense, therefore, Watt is an important work in Beckett’s oeuvre, despite his declared dissatisfaction with it.

The main success of McGovern’s illuminating, and very funny adaptation of Watt, is that it surely invites either a first reading or a re-reading of Beckett’s novel. Then, as they say, the real fun begins. Ian Patterson

Photos by Pia Johnson