For a long time, it looked entirely likely that David Bowie’s final musical statement would be a number entitled ‘Funny Little Fat Man’, performed in an episode of Ricky Gervais’ comedy series exploring the underbelly of celebrity, Extras. Gervais was a massive Bowie fan (as was his character, Andy Millman), and in the scene, he struggles to hide his obvious delight that his idol is in on the joke, acerbically skewering Andy Millman (and by extension, Gervais) as an unfunny, unloveable loser, with the entire world joining in on the chorus.

Bowie, in total contrast to Gervais, is imperial, every inch the elder statesman he’d become, playing to the crowd, but also lost in the moment of creativity with genuine relish. As far as farewells go, it’s pretty good.

But of course, that wasn’t the end, and after a long period of silence, Bowie reappeared with The Next Day, and now, finally, Blackstar. His death at the age of 69 gives Blackstar a poignancy that it will struggle under the weight of, becoming (and intended to be, evidently) ‘Bowie’s last statement’. But then again, all of Bowie’s albums, to some extent, offer some kind of personal narrative on the artist and his place in the grand scheme of things.

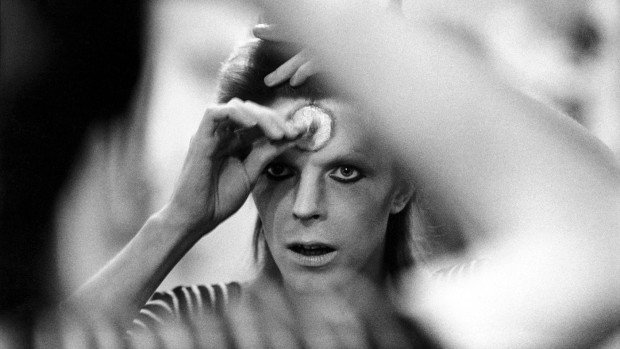

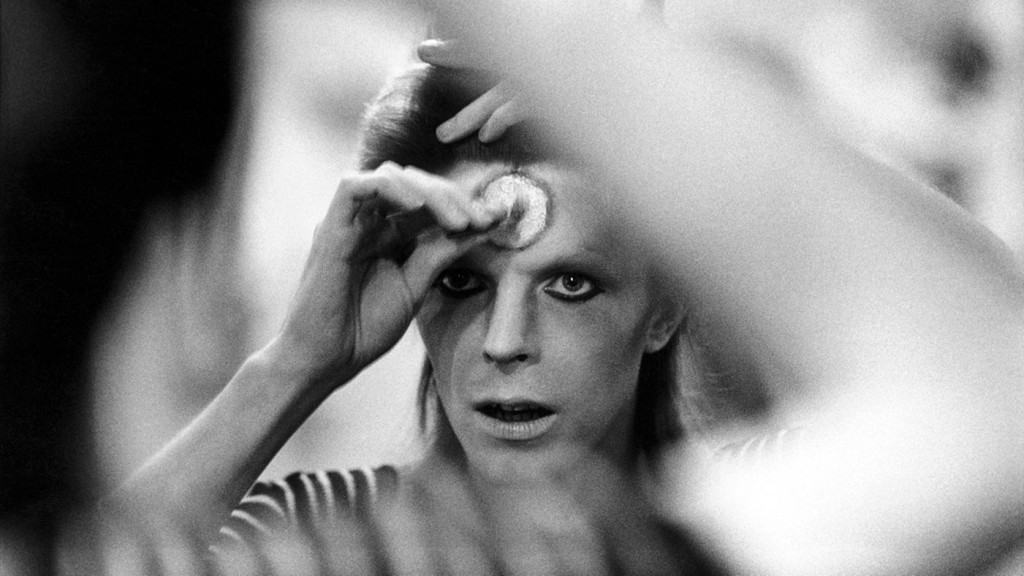

Right from the beginning, much of Bowie’s music has focussed on him, and his own space within popular culture. His oft-celebrated gift of reinvention allowed him to be both the focus and the subject of his pop-cultural lens, and as such when people say, “Are you a Bowie fan?” it might be more useful to ask, “What part of Bowie are you a fan of?” Perhaps more than any other artist in popular music, an interest in one of Bowie’s albums or songs does not necessarily ensure a love of anything else he’s put his name to.

The folk singer years meld into the glam rock operatics of the early 70s. 12 bar blues morph into plastic soul and funk, before funk gives way to chilly electronics and soundscapes. Pop music rears its ugly head in the 80s, and in 1984 with Let’s Dance, Bowie begins to stumble, a stumble from which he never truly recovered as an artist. The 90s were spent largely obsessing about ‘relevance’ and his own legacy, finding him struggling to get his head around drum & bass, whilst coming to terms with his work in the 70s, celebrating the incredible back catalogue he created in absence of adding to it. By the 21st century, Bowie retreated from view, and let his past do the talking.

The Next Day and Blackstar show an invigorated artist, pushing for something new. The self-preferentiality is still there (‘Where Are We Now?’, an emotional highpoint of The Next Day is almost entirely dependent on knowing Bowie’s own biography), but the desire to create is in full display. Particularly on Blackstar, Bowie is an artist, making art for its own sake.

And in a realistic sense, this is where Bowie’s real genius lies. Rather than breaking new ground, pushing boundaries, and reinventing the fabric of art itself (all of which it would be possible to claim he has done), Bowie is the ultimate cultural curator and interpreter. His finest and most celebrated moments find him as a connoisseur, casting his critical eye over other people’s work, and then repurposing it for his own needs.

Ziggy draws from writers like William Burroughs and JG Ballard to create his sci-fi narrative, whilst the celebrated ‘Berlin’ period in the late 70s finds Bowie absorbing the music of bands like Neu!, Harmonia, and Brian Eno, but refining it and making it work for a mainstream audience. Even by the late 80s, when Bowie’s impact was waning, he still had the Midas touch, namechecking the likes of The Pixies, or Nine Inch Nails, with his cultural compass still on point.

Looking back through all of Bowie’s best music, it’s frequently easy to find the point of origin, and work your way back. In the best possible way, David Bowie is an almanac of popular culture in the 20th century, a fascinating history all filtered through his own refined tastes. Never quite a progressive revolutionary in his own right, Bowie had that rare gift of being able to know what is ‘good’, and giving it back to an audience who’d never been exposed to it.

So, when the New Romantics thank him for the glam years, and the post-punkers thank him for the Berlin period, what’s really happening is an entire era acknowledging that the seeds were sown by this one man with his finger on the pulse. Is the influence that German electronic music has upon contemporary music significant? Of course. Would it be the case if Bowie hadn’t championed it and incorporated it within his own music? Perhaps not.

The Next Day and Blackstar round things out, with Bowie running out of things to share with the world. The Next Day found him reminding the public of just how good David Bowie was, even re-appropriating his own cover art, whilst Blackstar shows us the kind of thing that a David Bowie should be up to, without necessarily ever hitting the heights of the late 70s (not that anyone could). With 21st century culture so utterly dominated by Bowie’s beloved internet, we can all be Bowie now, something that was presumably not lost on him. The need for someone to go on cultural safari and incorporate a host of esoteric influences into their own art, with the express purposes of sharing it with us (and by proxy, appearing at the forefront of a new scene) is kind of over, and cultural tastemakers are a dime a dozen now. All that we can hope for is that they have the same good taste as Bowie.

Looking back to his appearances on Extras, it’s the one side of Bowie that we rarely got to see. He’s playing for the crowd, encouraging them to sing his chorus of, “See his pug-nosed face,” whilst pointing and laughing at Ricky Gervais, but he’s mainly playing to himself. He has nothing left to prove, not sure if he ever will again. Alone in a crowd of people, conjuring music from the ether, he can finally discard all the changes and be himself.

And he is content. Steven Rainey