George Best: All By Himself begins in darkness, with the voices of commentators eulogising George Best’s remarkable footballing talent, before the dreamlike moment is shattered by a recollection of Best’s ex-wife Angie of seeing a homeless man walking along the road, only to realise it was George. In Daniel Gordon’s documentary, football is secondary to the tragedy of Best’s personal demons, as Gordon attempts to unravel the enigma and get to the root cause of the star’s dramatic decline into alcoholism.

Gordon’s film unfolds in a largely chronological structure, taking the audience from Best’s humble beginnings, through his meteoric rise to the greatest footballer in the world and then the long, ignominious fall from grace. Interestingly, there are no marquee names involved. Gordon instead adopts a much more small scale and personal approach, interviewing those who knew George the best, with an inner circle of friends, agents, teammates, girlfriends and wives contributing, as well as archival interviews with Best himself and his mother Anne.

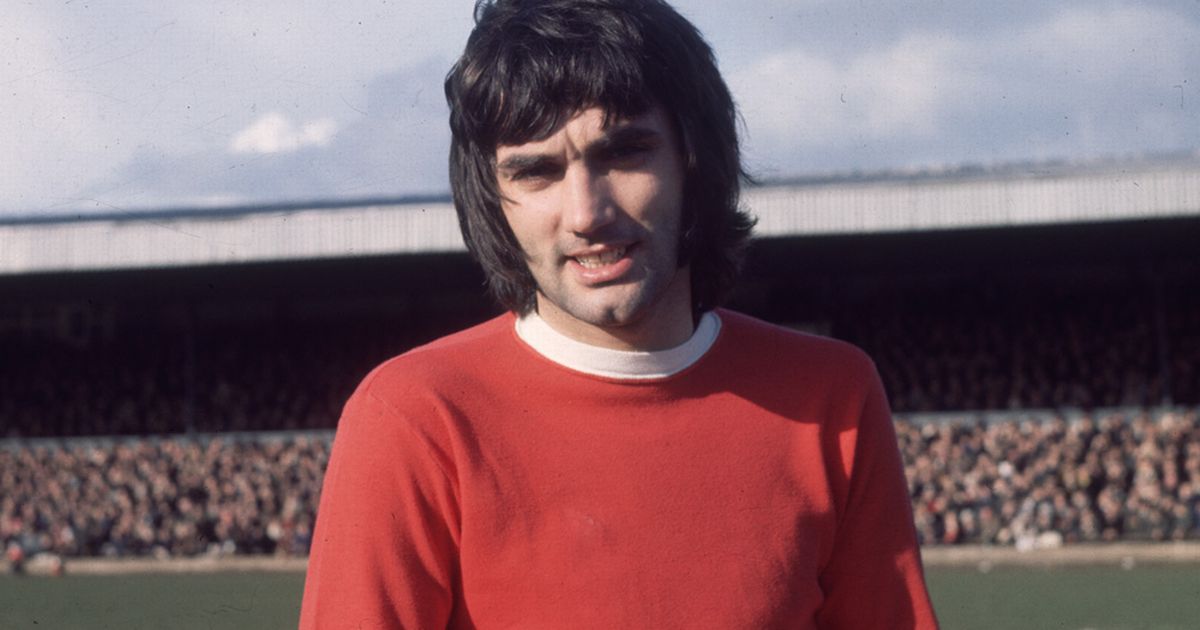

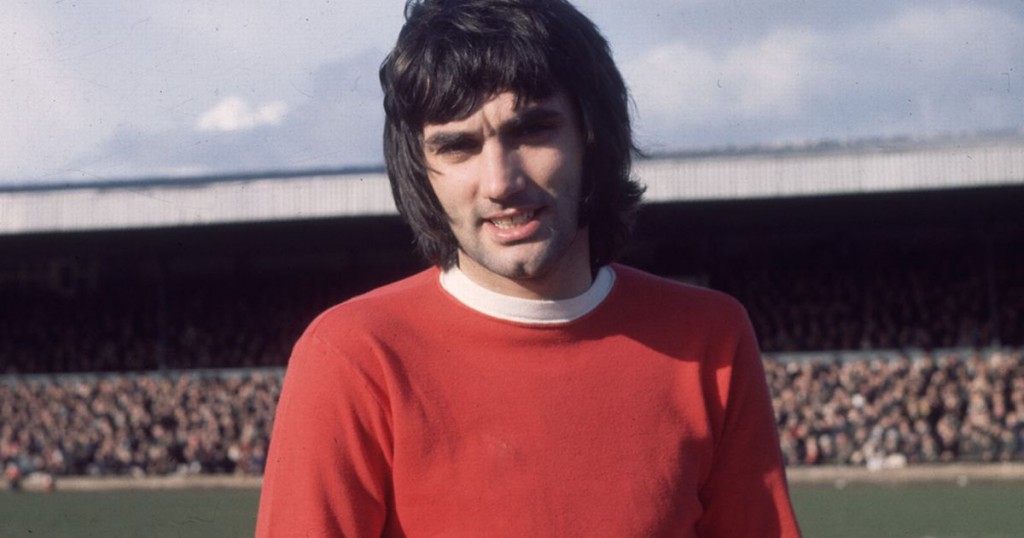

The film begins by establishing Best’s character before the fame and the drink: a shy, quiet boy who became homesick after one day of his initial trial with Manchester United in 1961. By 1966, however, Best had announced himself on the world stage after a stunning performance in a European Cup tie against Benfica. Returning home with a sombrero on his head, he was dubbed ‘El Beatle’ by a newspaper and that was the beginning of his life in the headlines. After this, George Best would never just be a footballer again, as the film chronicles with a deluge of advertisements, autograph signings and interviews from the time.

One sequence in the film that does occur out of chronology in the film is when Gordon takes time to recount the details of the Munich Air Disaster in 1958. One of the greatest tragedies in football’s history, which saw the loss of a promising generation of players on the cusp of greatness, it is crucial to understanding the context of Manchester United’s 1968 European Cup victory over Benfica, Best’s finest hour as a player and the lynchpin of his career. Winning the European Cup and lifting the long shadow of Munich was the greatest achievement possible for the club: it was the be all and end all, especially for survivors of the disaster such as captain, Bobby Charlton, and manager, Matt Busby. Thus, with this achieved by the age of 22, and the club’s rapid decline into mediocrity following Busby’s retirement, Best was left with football, which had previously meant everything to him, meaning less and less. Best’s love affair with the game was dying, soon to be replaced by two other passions: women and drink.

Best offers multiple narratives for George Best’s drinking and his inability to stop, from his natural shyness, to filling the void of the buzz of football, to a coping mechanism for the pressures of fame. The most compelling of all, however, is Best’s naturally good, but undisciplined, character being unable to cope with letting people down. Time and again in the film, interviewees comment upon Best being a terrific person. Shame and guilt, it seems, drove him much further down the garden path than most.

George Best’s story is a very familiar one to audiences, but where this film rises above others is in the incredible array of behind the scenes photos it features. A narrative of a man alone is constantly reinforced by vivid images such as Best juggling a football amidst the vastness of an empty Old Trafford stadium. Photographs of incredibly happy times in America, where Best found anonymity and love, only add to the sense of tragedy the audience feels. Saddest of all, however, is the inescapable sense in photograph after photograph that Best, behind the eyes, was a man haunted by his own actions.

For football purists, Best does not really come close to giving a sense of how brightly George Best shone on the pitch, instead concentrating on his life off it. Best feels slightly unbalanced as a result, with his much less-documented time in America dominating the second half of the film, and in spite of the depth of research that has clearly gone into the film, the newly commissioned interviews and the testimony of Best, himself, there is still a sense that the man remains as elusive now as he ever was on the football field. Richard Davis