Few events in Belfast are likely to be as emotionally charged as this evening’s tribute to Sparklehorse. Anyone familiar with the band’s output -and it immediately transpires that not one soul in tonight’s intimate gathering does not hold every beat, note and lyric in their hearts – will already know that frontman Mark Linkous took his own life seven years ago. That fact, tragically, is unavoidable, and there is certainly no avoiding the spectral shadow that such an unnecessary and painful loss casts over the entirety of Linkous’ back catalogue. It is impossible to listen to his music without feeling the sharp pangs of bereavement, more so because the singer always treated his own voice with something approaching disdain, masking his vocals with distortion, interference and distortion. However, to hear an artistically disembodied voice is one thing; to hear one that has left the owner’s body for real is another thing entirely. When any of Linkous’ songs – and he wrote such pretty and fragile songs – are played this evening, the room swells with collective heaving chests, bristled napes and, it is no surprise, dampened eyes.

But it is also an evening marked by sheer joy and nostalgia. Before the event begins in earnest, several of the conversations focus on when folk first saw or heard Sparklehorse. For many, it was a seminal gig in The Empire, 1999, and the haunted ballroom was the perfect venue for the otherworldly sound of the music. For others, it was receiving a promotional copy of ‘It’s A Wonderful Life’, which is for many the creative apex of the band’s oeuvre. The juxtaposition of sadness and joy is fitting. Linkous, it is often said, was a man caught in two worlds, riding his motorcycle – one of his precious gasoline horseys – between a cabin in the forgotten woods to the claustrophobic city which he grew to resent. Or trapped between different channels: like Alice, on the other side of the glass, or poor Barb, in the upside down. Or, more accurately, like Elliott Smith, slipping between the bars. Linkous’ music was appropriately polarised. He was a master at combining dreamlike, poetic ballads with cathartic noise – occasionally, in the same song.

Of course, such a stark division suggested that Linkous was a troubled and often tortured individual, and this schism is confirmed by the chosen title for the documentary The Sad & Beautiful World Of Sparklehorse. To its credit, the film does not shy away from the sad experiences that shaped Linkous’ time on earth. This is very much the story of two deaths, not only the obvious one that curtailed his life but also a formative experience in a London hotel room in 1996 when an overdose nearly left him paralysed from the waist down. Linkous collapsed with his legs trapped beneath his body, leading to a harrowing story of heart attacks, surgery, touring in a wheelchair and wearing leg braces for the rest of his life. The resulting depression would both fuel and hamper Linkous’ songwriting in subsequent years. The obstacles that plagued him made Linkous more emotionally attuned – “It’s a hard world,” as he put it, channelling the film Night Of The Hunter, “for small things.” At the same time, the cycle of writing, recording, promoting and touring took enormous toll on Linkous’ mental and physical health. This might explain why he spent five years living in a cabin on the side of a mountain two hours from the nearest settlement.

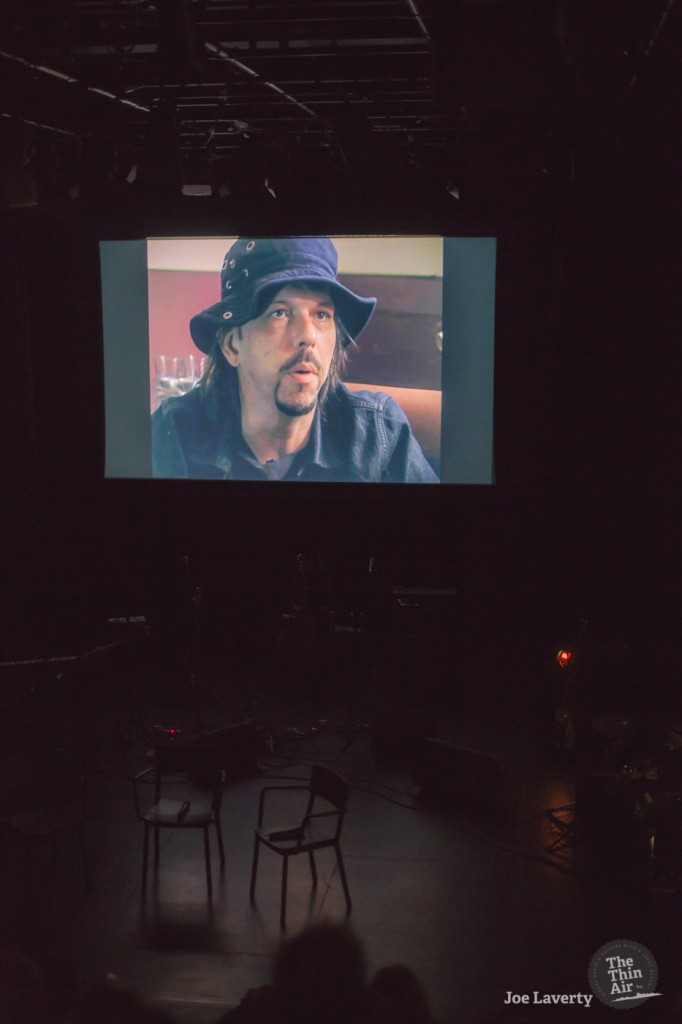

In the film, many of Linkous’ friends and collaborators, including Jonathan Donahue, Jason Lytle and David Lowery, comment again and again how Linkous struggled with the minutiae of the humdrum: the daily slog of paying bills and repeatedly pushing that infernal boulder up a hill. It is abundantly clear, particularly in Donahue’s eloquent monologues, just how profoundly the loss of Linkous has changed them. Some of the most affecting moments are when these contributors, who rise far above the regular standard of token talking heads, recall anecdotes of their colleague’s warmth, generosity and humour. One of the documentary’s most surprising elements is that it is at times very funny: early footage of Linkous playing with his first band The Dancing Hoods is complemented by an old-school news anchor getting to grips with “indie rock” in the sweetest way imaginable. Linkous himself was clearly an endearing figure: given his reticence towards doing promo, there are few interviews, yet in any of the existing material, most of which was filmed by the documentary’s directors Alex Crowton and Bobby Dass, who elaborate further upon this quality in the Q and A that follows the screening, Linkous is portrayed as genuine, down to earth and, in a very real sense, childlike. This is in no way an insult. Rather, as with Nick Drake or the aforementioned Elliott Smith, Linkous is communicated as an individual unequipped to deal with the harshness and frustrations of day-to-day life. In fact, at times the film becomes an impassioned clarion call against the American medical care system – or lack of it. Time and time again, we are told that Linkous, particularly when he was at his lowest ebb, did not have access to, or could not afford, appropriate mental health provision. Naturally, it would be too easy to turn these sections into embittered propaganda against an ineffective American government yet the focus is very much on the individuals who suffer as a consequence of defective politics. What ifs are utterly futile yet it is all too tempting to wonder how Linkous might have been helped had he been cared for by a more altruistic system. Or indeed, how it could have helped his friend and collaborator Vic Chestnutt, a quadriplegic who also took his own life, and whose death had a determining effect on Linkous himself.

Again, all of this discussion might suggest that Crowton and Dass’s film is maudlin and self-indulgent, yet this is far from the case. Any rough edges are smoothed down by narration by musician Angela Faye Martin, who directly addresses Linkous, almost as a mother would speak to their child, and whose voice is rich with pathos and fondness. Martin’s screenplay sews together the disparate elements of Linkous’ life and career, and adds a very real human element to what, in less careful hands, could have become just another tedious hagiography.

In The Sad & Beautiful World Of Sparklehorse, Crowton and Dass have made a documentary that is as loving as it is detailed, one that, in spite of the dark subject matter, is notably optimistic. It is a wonderful life, after all.

This affection continues after the screening, where an ensemble of some of Northern Ireland’s foremost musicians play no less than fifteen versions of songs culled from the entire Sparklehorse back catalogue. Tom McShane, Pixie Saytar, The Mad Dalton (who was instrumental in organising this whole event) along with members of Heliopause and Junk Drawer, do their damnedest to recreate Linkous’ signature sound: the joyous squall of ‘Happy Man’, the lamenting ‘Eyepennies’, the eerily crepuscular ‘Spirit Ditch’… you can feel the audience willing the band to succeed, and in turn the band handles the source material with remarkable aplomb. What is abundantly clear is the love that each of the artists involved have for Linkous, and the care with which they want to treat his legacy. They do so accordingly: there is no posturing in this performance, and no glory-hunting, even though any praise would be justly deserved. The focus is very much on a band called Sparklehorse and the incredible records left in its absence. Ross Thompson

Photos by Joe Laverty