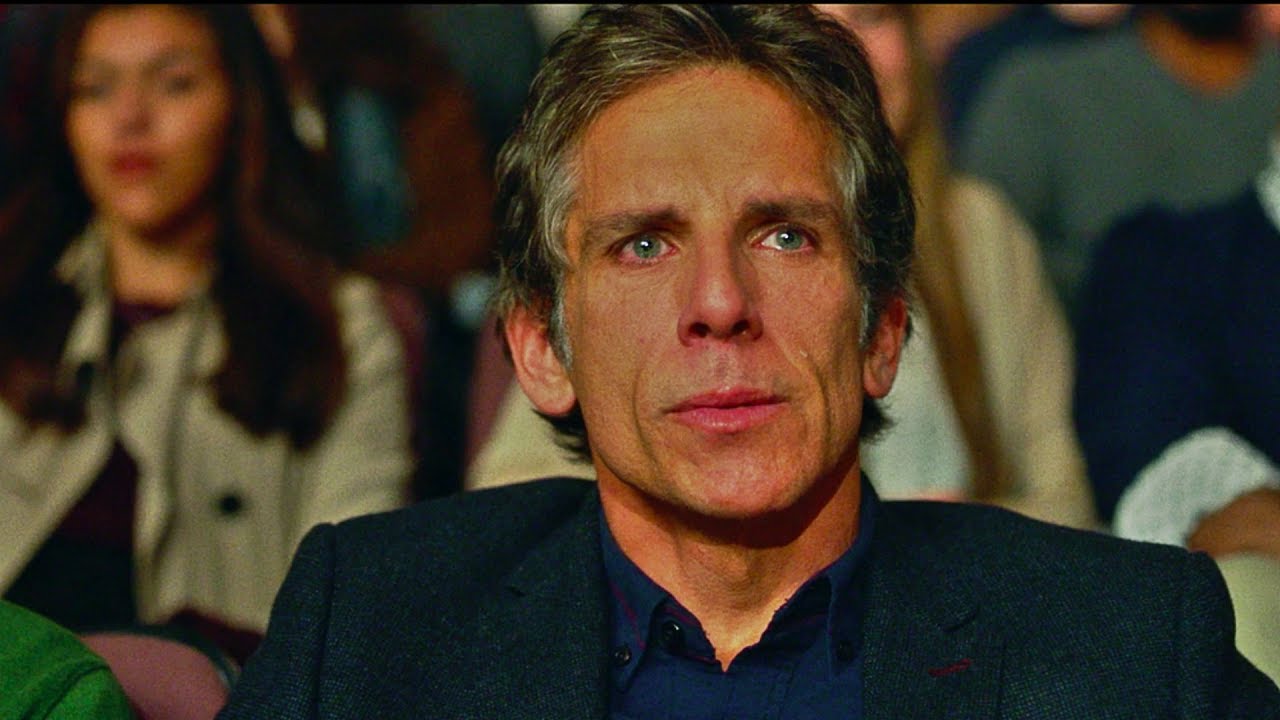

‘Everyone is just thinking about themselves; they’re wrapped up in their own stuff’, high schooler Troy Sloan tells his father, who is hunched over the edge of his hotel bed, haunted by deep, formless feelings of failure. The comment is meant to reassure Brad, who has spent their college-tour trip suffering through bouts of jealousy and insecurity, and it’s the sort of line routinely served up to sooth the self-conscious. Everyone’s caught up in their own stuff, no-one even really sees you, so stop worrying so much. But Brad’s problem is that he’s already too self-involved, Ben Stiller’s wounded, jittery eyes communicating a man tangled up in loops of anxiety.

Brad’s Status is screenwriter Mike White’s second directed feature, a decade after 2007’s Year of the Dog. Like his brilliant, under-seen HBO series Enlightened, which starred Laura Dern as a grating suburban hippy, the film is a narrow but carefully crafted window into the inner life of privileged neurotics.

By any metric, Brad lives a comfortable existence. He runs a charity consultancy (which he describes, tellingly, as a ‘start-up’ to his son’s friends), and lives in a nice Sacramento house with his schoolteacher wife (The Office’s Jenna Fischer) and son Troy, a talented, grounded musician who has Harvard in his sights. Middle-aged, settled and restless, he cannot shake feelings of inadequacy, torturing himself with envious daydreams about the glamorous lives of his old college buddies, who cut him out of the loop a long time ago. Craig (Michael Sheen) is a TV talking head who worked at the White House; Billy (Jemaine Clement) lives a life of leisure in surfer’s paradise; and Jason (Luke Wilson) is a hedge fund multi-millionaire. Brad is trying to be happy for his college-bound progeny, but his mind’s eye is stuck in comparison mode, a film loop of rich, beautiful one percenters with commercial-ready smiles.

Brad’s Status sounds unbearable, then, a sad sack story about a mopey middle class white man, but White knows how to build emotionally sophisticated drama out of obnoxious-sounding conceits. With his fixation on perceived indignities and much-cherished little victories, Brad experiences the father-son trip to East Coast campuses as a minor cringe comedy, betting his self-esteem on upgrades to business class or using contacts to snag an admissions interview. Troy (Austin Abrams) is a nice foil to his jittery father, quietly mortified and baffled by his dad’s on-edge attitude, with a genuine teenage indifference to the status symbols that make Brad’s eyes flicker.

Fantasy sequences and voiceover narration hem the viewer inside Brad’s head, a magic lantern show of imagined humiliations. He pictures Troy becoming an accomplished musician and the proxy glory of telling other parents; then he sees a snarky Troy on late night TV, joking with Jimmy Kimmel about his weirdo dad back home. He is, ludicrously, jealous about the success of his own son, before his son has even done anything.

Brad’s Status seems firmly etched within mid-life crisis territory, but it’s real subject is more universal and intractable: our habit of comparison, not simply with other people, but with the version of them we carry around in our heads. Out of Brad’s buddies, he only ends up meeting one face to face, the others getting short scenes of telephone conversations, existing primarily in his whirling internal wheels.

White’s screenplay skirts nimbly around cliches and cop-outs. There’s no revelation in which Brad realises he’s pegged them all wrong, and vows to change and ‘appreciate what he has’. The film keeps the accuracy of Brad’s internal images unclear, the point being not whether or not these people are successful, but why that information matters in the first place. The ending’s re-orientation towards the world provides some hope, tempered only with the real possibility that its protagonist’s inability to stay present is a problem without a solution. A pithily ambiguous final line leaves Brad’s final status unclear. Conor Smyth

Brad’s Status is showing at Movie House Dublin Road, City Side and Lisburn Omniplex.