At the beginning of Palme d’Or-winning The Square, another cold, almost hypothermic portrait of male insincerity from Force Majeure’s Ruben Östlund, a successful Stockholm art curator is interviewed by a nervous journalist (Elizabeth Moss). With his fey scarf, bright but not unfashionable socks and red designer spectacles, tactically removed to communicate casualness, Christian, played by Claes Bang, is every inch the dreamy modern intellectual.

When Moss’ interviewer asks him to unpack the dense description of one of the museum’s events, an investigation of the ‘topos’ of the exhibition space, he struggles, offering a glib line about the validity of normal objects becoming ‘art’ when placed in the gallery, the sort of meta-theory familiar to any first-year student art theory. It’s the start of the film’s pricking of arty loftiness, flagging academic jargon as a way to obscure and impress, but the idea of the museum as a malleable, undefined space is also a clue to The Square’s disparate targets.

In this version of the Swedish capital, the gallery aesthetic has infected everywhere, its anemic greys and hard lines swallowing streets, shopping centres and even interior decoration. Billed as a satire of the modern art world, Östlund’s film is actually less niche than that, taking on a certain kind of enlightened urban sensibility, Scandinavian restraint and the self-satisfaction of the European project more generally.

This is a world where nothing real really happens. Until it does. While Christian is walking to work, an off-screen girl’s cry for help interrupts the smooth, pedestrian commute. She runs to a stranger, manic, who looks to Christian and gets a ‘nothing to do with me’ half-shrug, the automatic reflex for non-committal guilt, and one that recurs in the film. It’s a set-up; the girl’s pursuer crashes into them, and Christian’s wallet and phone are swipped. But before he realises the trick he’s elated, him and the other man bonded over the random craziness. And even after, he covets the encounter, eager to tell the story at work, the robbery the twist at the end.

Christian’s plan to retrieve his stolen property, conceived in a burst of excited machismo, produces unforeseen consequences and awkwardness. Meanwhile, the gallery is gearing up for the promotion of a new installation, ‘The Square’, a space where people are obliged to help others who need it, designed to test the social contract between patrons.

Östlund cuts away regularly to the beggars and rough sleepers of the city, and stages multiple scenes of ignored requests for help to underline his not-so-subtle point about the hypocrisies of abstract ‘issues’ and the dangers of automatic behaviour. With their unsophistication and neediness, they stick out like eye-catching exhibits on blank walls. Cogs of art market cynicism come under scrutiny, like a PR agency whose obsession with going viral produces a spit-take promo video, but the film is more atmospheric and abstract than specific. It is perhaps too long, but there is a stifling, creeping, anti-social mood, an evasiveness and distance evident, for example, in the way that Christian talks to other people.

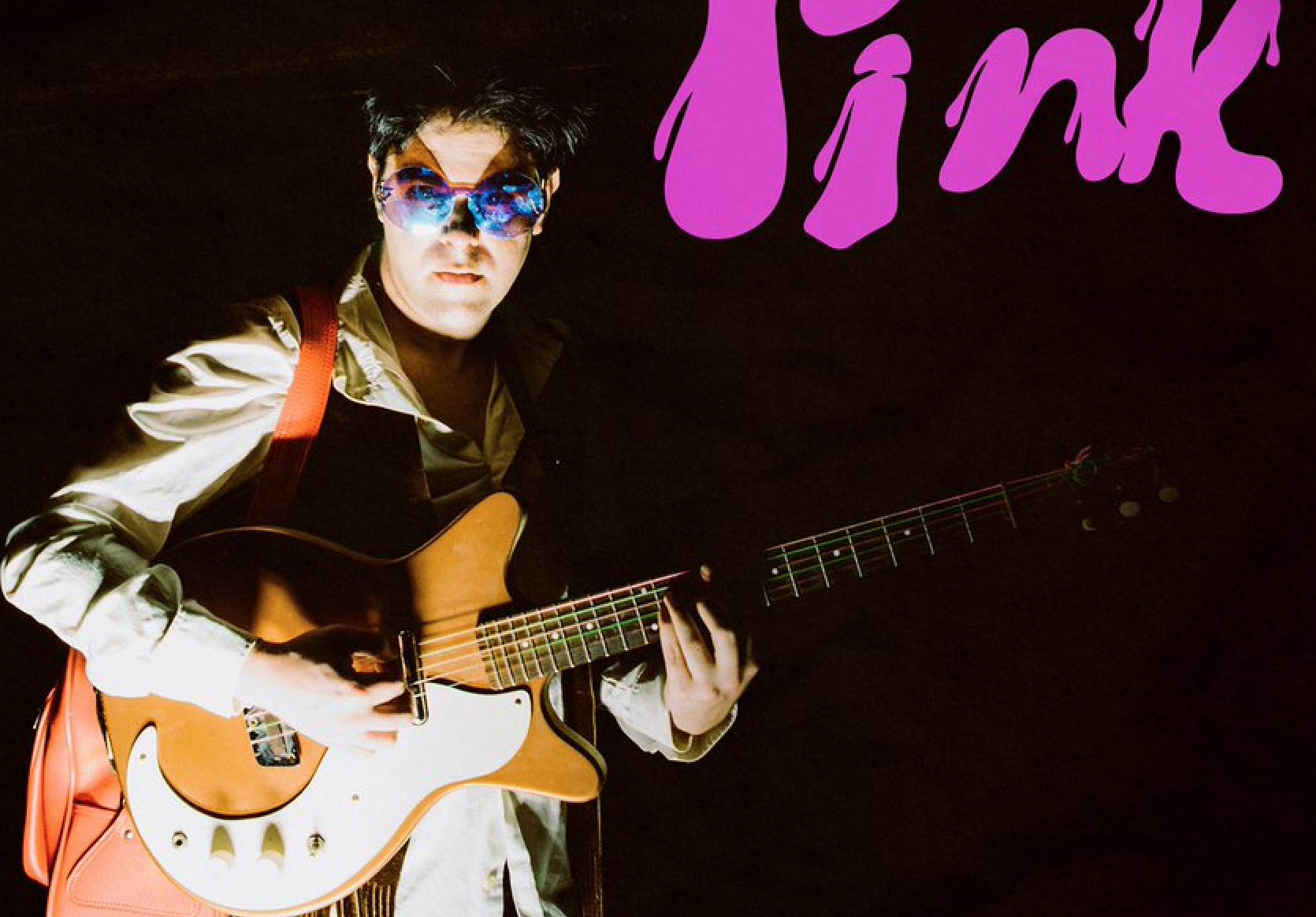

The Square likes its interruptions, the nervous, anxious moments when standard protocol is suspended, like profane Tourette’s chatter at a visiting artist Q&A (Dominic West in bell-end sunglasses). The film’s standout scene, which has nothing really to do with the main plot, is a fantastic banquet hall set-piece built on opposites and escalating tension. The entertainment provided for the donor class is a wild performance piece in which a topless beefcake artist (a savage performance from Terry Notary) gives a physically committed simian impersonation, breaking through the initial silliness with gasp-grabbing boundary violations.

The scene is the most direct expression of subtextual warnings about the cowardice we call politeness, and the weakness of the comfortable class when faced with genuine threat. Set against the conflict-avoidant personalities that dominate chilly Stockholm, it’s jammed in the middle of the film like dynamite in granite. Conor Smyth

The Square is showing at Queen’s Film Theatre, Belfast and the Light House Cinema, Dublin.