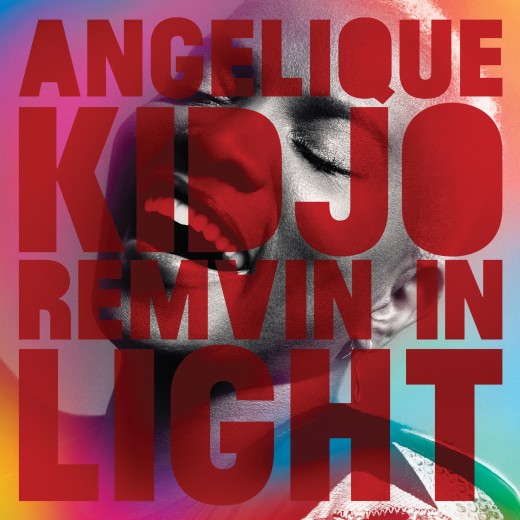

To describe Talking Heads’ Remain In Light as one of rock music’s sacred cows would not be unfair. It’s a seminal album for a good reason. Over its eight songs, it manages to capture the best of Brian Eno’s kitchen sink experimentalism, David Byrne’s existential mania, and improbably groovy rhythms. It manages to do all of this while successfully fusing the group’s post-punk roots with a wide array of Afro-Carribean influences to create profound and stridently individual, one of the 1980s greatest idiosyncrasies. So when the Benin-born artist Angélique Kidjo announced her intention to reimagine the album and reclaim it for Africa by expanding on its African influences, reactions were mixed. On the one hand, Kidjo is a musician of such an incredible stature and talent that it would hard to imagine her doing a disservice to the music. On the other, the songs hold such importance that any deviation from the original at first can feel intrinsically wrong. Fortunately, the former camp was correct here. While Kidjo’s interpretation doesn’t reinvent the wheel or discover too many new layers to these pieces, it gives them a fresh lease of life and us a new way to appreciate their vitality.

One of the great pleasure’s of the album is hearing just how far Kidjo is willing to push these tracks to the limits of recognisability. Songs like ‘Once In a Lifetime’, ‘Houses In Motion’ and ‘Born Under Punches’ are pioneering slices of rock music. But Kidjo has no interest in protecting or shielding them. She wants to tear them asunder and expose the beating heart at its core; a feat she effortlessly achieves.

‘Born Under Punches’ opens with s smooth vocal section that wrong-foots you pretty heavily. For those first few bars, it’s hard to know exactly what she’s doing. It’s only when a thick, distorted synthesizer delivers the song’s unforgettable hook that can you reorientate yourself. What becomes apparent very quickly is how earthy and natural everything sounds. Where the original gets swept up in the trappings of electronics and the coldest of modernity, this has a much warmer sound and more soul.

The horns of ‘Seen and Not Seen’ manage to take the album’s most upsetting cut and make it into something more tragic and human. The same can be said of the flutes and gentle guitar work of ‘The Overload’, a song which was intended as Joy Division pastiche. She even succeeds in add an extra layer of groove to the impossibly funky to ‘Houses In Motion’. The emphasis on the natural, roots-based instrumentation gives these versions a deeper sense of personality and purpose. It’s this character which justifies the whole endeavour.

While the songs are pretty much fundamentally flawless, Kidjo’s renditions don’t really add enough to make them stand out. They mostly amount to interesting, joyful curiosities. The only exception to this would be ‘Once In A Lifetime’ which, as with its parent record, is the absolute standout. It was this track which inspired this whole experiment. As such, this is the most manicured and realised piece on display. Gone is the anxiety attack which defined the original. In its place is this slice of passion and joy. Where Byrne’s version has that sense of someone losing grips with reality and spiralling into themselves, Kidjo’s has a communal soul at its centre. The conflict is still the same but, in this form, rather than slipping into solipsism, we fall into a vortex of community and collective spirit. We may be alone in our minds, but outside we’re surrounded by love, care, and the natural world. This cut is an absolute delight from start to finish and is a shining example of what this artist intended, and largely succeeded, in doing. Will Murphy