Nas prefers a raucous homecoming to the sanctum of a rustic ski-resort in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, it appears. Beneath a constellation of NYC lights, in the imperialistic surrounds of Queensboro Bridge — a staple of hip-hop iconography made famous by MC Shan in 1987 — lay double-decker speakers blasting amid a sense of godly reincarnation. It’s the first-listen party for Nas’s latest full-length record, Nasir. One time wunderkid, Nasir Jones, chose his city, his borough, to celebrate this album’s release; where he spoke, for the first time, his tightly-wound, unadulterated, street-scholarly truth. Where he first etched his name into hip-hop folklore, with careful, clear-eyed precision and calculation.

Truthfully, though, Nasir — Nas’s 12th studio album, executively produced by Kanye West — is not the self-titled, self-referential album which lends itself unto a personal statement of the man, Nasir. A proud byproduct of the sprawling, multi-dimensional metropolis that is New York City: his name is New York City, his name is Queensbridge, hence the album title.

Timing is everything in hip-hop, and a reference to the recent Starbucks racism controversy provides Nasir with an air of immediacy. However, given the timing, the complete absence of self-examination or addressing of his ex-wife Kelis’ allegations of mental and physical abuse, when positioned alongside his nemesis-turned-collaborator’s 4:44 — Jay-Z’s repentant, grown-man, confessional 2017 record — highlights a glaring blind-spot. On the cover of 2012’s Life Is Good, Nas sat ruefully with Kelis’ wedding dress draped over his knee, a cover and album that, in light of the recent shadowy revelations, beg for a reexamination of the album’s purported fleshing out of marital shortcomings: Nas’s fragile victimhood now reeks. The spectre of the grotesque allegations, tucked away for years, hang like asbestos between Nasir’s cracks and crevices.

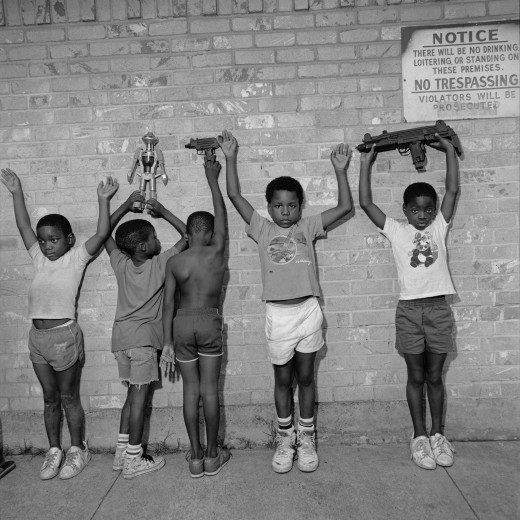

There is, too, a cognitive dissonance between much of the album’s subject matter and the man who helms the production. After publicly cosying up with right-wing conservatism, almost overnight becoming a Breitbart-reader posterboy online after exoticising MAGA (and later stating slavery was a willful choice for slaves) — it seems at odds for Kanye to spit in a verse unrestrained about institutional racism and police brutality on ‘Cops Shot The Kid’.

Kanye’s production on Nasir is less kaleidoscopic and maximalist than on his psychedelic Kids See Ghost collaborative project with Kid Cudi — instead sharing much of its DNA with Pusha-T’s excellent DAYTONA album. The production is, however, as invitingly neurotic as its maker: There’s artisanal, soulful, RZA-inspired beats (‘White Label’, ‘Adam and Eve’), a trippy, face-melting loop of Slick Rick on ‘Cops Shot The Kid’ and fine-tuned, orchestral grandness on ‘Not For Radio’. At times, the beats crumble in their own cerebral Pete Rock folly, yet they should provide enough pockets of space for even the most basic of rappers to shine.

Ultimately, Nas’s performances are meagre; starved of focus, wit and rigour. Like on most Nas projects, there are also some questionable lyrical moments: On the cinematic album opener, ‘Not For Radio’, during a shotgun blast of confused, faux-deep knowledge-bombs, he claims Fox News was started by a black man. In light of Kelis’ now-public stories of patterned, drunken, violent abuse, the lyrics — “Neck choker/In her mouth spitter/Blouse ripper /Ass gripper” — seem at best to be highly inappropriate and, at worst, jarringly pointed machismo. There’s also protracted anti-vaxxer sympathising on the lowkey, ‘everything’, a perplexing continuation of something he first revealed on Stillmatic.

Nasir does, in all of its failings, paint a picture of an artist faithful to tradition, to penmanship, to imparting soaked up wisdom: This is where the album falls as much as it succeeds. If you stencilled Nas’s flow patterns from ‘94, imprinted them on nostalgic Kanye West production, packed the bars with blurry narratives and surreal flashes of Nas’s esoteric brilliance — you get Nasir. On the queasy, Tony Williams-featuring ‘Bonjour’, Nas flexes, griping at one juncture that some crackheads still owe him from ‘89. This is the Nas that enraptured a new generation of rap stylists. In the catacombs of ‘Adam and Eve’, over a jittery, melancholic, piano-loop of the Iranian singer-songwriter, Kourosh Yaghmaei, Nas brandishes his pen with greater recoil than on much of the skimpy, seven-track album; the noirish imagery blood-stained, his cadence venom-laced. (“The ghosts of gangsters dance/Chinchillas shake on the hanger, the force of this banger”). A few short bars later, he continues to rumble wrathfully: (“The clouds scurry, your spirit rumble, a boyish smile”).

Nas always seemed like someone who was sedated by the diamond-dancing lifestyle that his revelatory raps birthed: All too aware of his unimpeachable mythology, painfully unaware of the mostly substandard, formulaic and sonically scant albums he released post-It Was Written. Here, on Nasir, he sounds sloppy, deflated and uninspired. For the most part, Nas’s flows meander and sound achingly tired. ‘Bonjour’, in particular, suffers from an innate tediousness, courtesy of a stuffy Nas delivery and mediocre Bandcamp-backend hip-hop beat. The failed self-empowerment experiment, ‘everything’, sees Nas at his most nondescript, going through the motions, limping at times, as Kanye’s cartoonish vocals undermine any sense of true emotion on the hook: The poignancy, like on many Nas album tracks down the years, feels conventional rather than heartfelt.

Throughout his career, Nas has often toyed with abstract concepts: whether absurd or within the realms of possibility; whether social or political; whether physical or metaphysical. But, disappointingly, on Nasir he struggles to nail down any particular idea with effect. On God’s Son, he grappled with the passing of his mother. Hip Hop Is Dead, is, well, self-explanatory. When Nas sounds most lucid and believable, limited as this may be on Nasir, he’s unspooling his own insecurities and fears about family trauma (“Pray my sins don’t get passed to my children”). But Nas rarely, if at all, deals with the autobiographical here.

Unlike past albums in Nas’s discography — good, bad, classic, off-colour — Nasir fails to narrow a conceptual focus, and, what begets this forcefulness, is arguably his most inconsequential album yet. Forgettable lyricism and production, gilded with vintage sheen, do little to save Nas’s grace. The prodigious architect of one of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time has, through his own alleged actions and inconsistent releases, left himself with a tangled legacy: Who exactly is Nasir Jones? Nasir’s scattered themes leave little to be unpacked, instead posing a variety of newer, more pressing questions. Unknowns that, one hopes, are answered in time. Colin Gannon