The strobes hit with unforgiving regularity. Across the humid room you see a couple kissing vigorously, their hands dancing over one another. You’re dancing too, twisting and moving your body simultaneously with guttural thumps of bass. A flash reveals the glistening face of the man to your left, he beams over and moves his jaw up and down inaudibly, his words pummelled by the entrancing waves. A tear suddenly sprouts from the outer corner of his eye, but rather than wipe it away he allows it to slide jerkily down his face. You turn to see someone else whose mascara is running, beside them another glimmering face. Each flash reveals yet another profile glowing with the unmistakable sheen of emotional toil, and so, with a laugh, you begin to cry too.

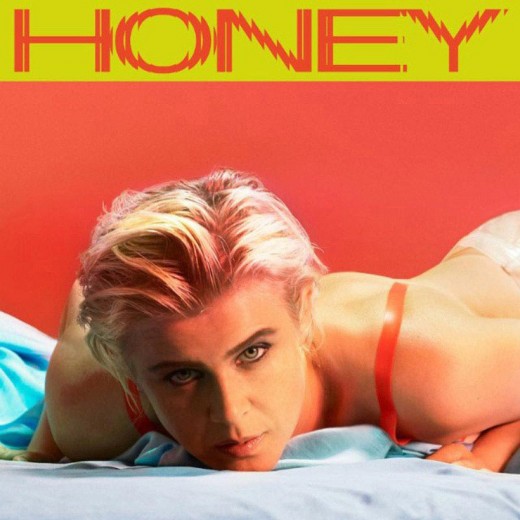

The typical ‘night out’ is often painted as a blissfully detached sense of joy, devoid not only of the worries that plague us during the nine-to-five, but also the ones that penetrate the minutes in between. A night out is, at its most basic, millennial core, meant to be focused on hours of joyous, narcotic dancing, ambiguous gossip and unknown potential – all means of forgetting about that boy who unmatched you on Tinder two hours before you were meant to meet for coffee, right? On Honey, Robyn dissolves this convoluted facade and takes us on a harrowingly accurate journey of exasperated catharsis. Rather than using the club to separate oneself from the emotional toil faced during the day, she acknowledges that we instead enter to feel these emotions with such force that we physically purge them; through blood, sweat, or tears.

It all begins with ‘Missing U’, a scintillating series of staccato synths guising the tear filled lyrics. Pulled together by an inclusive four four beat, we’re summoned to the dancefloor to spill out pain and confusion at the loss we have suffered. “There’s this empty space you left behind,” she sings. We often forget that people take up space, not in the physicality of our surroundings, but in the psychological world that we create for ourselves. We wrap ourselves with a security blanket of friends and family, but when someone leaves a draught can stir us into an intense cycle of discomfort and instability. This precariousness bleeds into ‘Human Being’, a sombre affair that moves away from the familiar club pop and instead lounges in metallic sheets.The shivering percussion makes less of an effort to mask the turmoil portrayed; repeating “I’m a human being” almost robotically, she communicates that, as we become more connected by technology, we also grow further away from each other, more easily being able to ignore or throw away people we otherwise would have interacted with.

You check the time and it’s nearing half past midnight. You leave the dancefloor and head to a bar illuminated by a blue strip of LED’s. The music slows a little for ‘Baby Forgive Me’, a mellowing grasp that circulates in a pleading desire for forgiveness, but as the sound melts into ‘Send To Robin Immediately’, a pulsating synth ruptures the need stricken absolution and you feel your body begin to surge with the power resembling ancient deities. You glide back to the dancefloor and as the domineering bass begins to roll in, the bodies join in thrashing elation. The time that follows is saturated with a sensation that can only exist following the expelling of agony. Burgeoning thumps on ‘Honey’ meld together with Robyn’s crystal like tones, the off key chords of ‘Between the lines’ send the entire club into a frenzy, and as the warm guitar plucks of ‘Ever Again’ ring through as the last song of the night, your hands join with strangers’, sweating bodies gleam off one another, and as a collective your soul rises and becomes galvanised with resilience and joy.

Standing forth as Robyn’s long awaited return, Honey brings with it an expectation that, for some listeners, will ultimately lead to their disappointment. While the album does contain the hard sought after electro-pop ballets that she has become known for, it’s also filled with experimentation that may lead to some tracks feeling incongruent, at least initially. Encapsulating the modern extension of what a ‘real’ night out is, from the tear studded faces of agonised strangers to the joining of hands with new brothers and sisters, Robyn manages to articulate the undertones of club culture better than many artists could ever hope to. For a growing percentage of people, she conveys an idea that alone we are formal, that we are liars to ourselves above anyone else. And so the club is truly the most intimate place to be. Mitchell Goudie