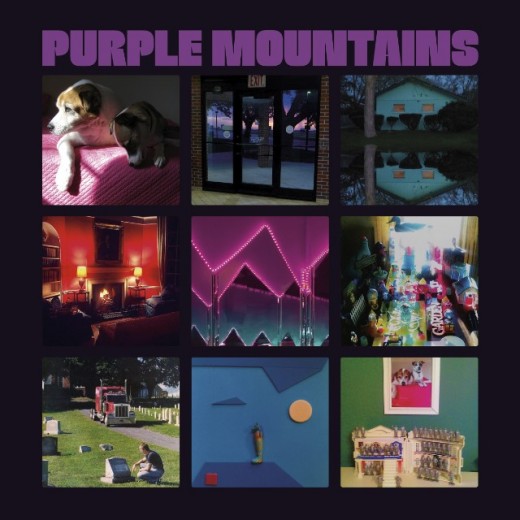

David Berman quit music in 2009. The reasons for retiring his two-decade spanning cult indie-country-rock project as Silver Jews were characteristically bleak. The disbandment, Berman revealed, was because he felt “the SJs were too small of a force to ever come close to undoing a millionth of all the harm” wrought by his Washington lobbyist father, known to many as Dr Evil. He also, relatable, just wanted more time to read and work on his poetry. Surprisingly then, this year came the announcement of Berman’s first album in ten years, the unexpected eponymous Purple Mountains – and it’s a tentative gem of a record, with as much glorious misanthropy as ever.

Straddling heartbreak, grief, and bitterness with his distinctive sardonic wit, his pairing of self-deprecating black humour with alarmingly catchy country melodies will be unsurprising for any veterans of the Berman universe – but even for a man who’s built his career around bleakly unabashed self-exposition, his first album as Purple Mountains is disarmingly vulnerable. His lyrics have always been candid depictions of a life consistently plagued by depression, failure, and addiction, but the way he weaves his personal life into frank portrayals of pain becomes universal. The fruit of a life devoted to words, a classic David Berman song contains what all good songs should; they are sad, funny and clever all at once, and he’s responsible for a back-catalogue of infinitely quotable one-liners, including possibly the finest opening line of any album ever; American Water’s “in 1984, I was hospitalised for approaching perfection”. His evocations of absurdity, melancholy and the heartbreakingly mundane are a masterclass in simplicity. His songs have always carried a strange and subtle weight, and this has been carried seamlessly into the songs of Purple Mountains.

The first track, ‘That’s Just the Way that I Feel’ is one of the most bluntly despairing songs on the album, opening with “well, I don’t like talking to myself / but someone’s got to say it, hell /I mean, things have not been going well / I think it’s time I finally fucked myself.” Later Berman attests to having “been humbled by the void” and refrains; “the end of all wanting is all I’ve been wanting”. Similarly heartbreaking is ‘I Loved Being My Mother’s Son’ in which Berman drops his wry approach and keens “when I couldn’t count my friends on a single thumb, I loved her to the maximum”.

It’s not an easy album, and at times listening feels almost indecent, as though, voyeuristically we are overhearing something we shouldn’t – similarly to the wrenching heartbreak of Mount Eerie’s devastating tribute to the death of his wife, A Crow Looked at Me, listening to Purple Mountains at times feels more like an anxious eavesdropping. However, despite its invitations into slightly unsettling voyeurism (and after all, that’s often been Berman’s charm) there are moments on the album that are just as rewarding as any jewel of the Silver Jews catalogue. Lead single ‘All My Happiness is Gone’ is one such song, and is quite simply a complete banger. It’s a scuffling country-tinged pop wonder awash with keys and the shimmer of latter-day-Jews-esque female harmonies, and enough pleasingly rhyming nostalgia and wallowing to make Morrissey blush. Over a jaunty tambourine Berman croons “ten thousand afternoons ago, all my happiness just overflowed […] nothing’s wrong and no one’s asking/ but the fear’s so strong it leaves you gasping”. Unlike The Smiths’ frontman’s cantankerous self-aggrandisement, however, one of Berman’s most endearing qualities is his ability to laugh at himself, and to laugh at the absurdity of a world so intent on delivering misery, he sings unapologetically about failure, pain and humiliation, but he always does so with a knowing wink.

Demonstrably, ‘Margaritas at the Mall’ is a testament to everything that makes Berman the brilliant writer that he is. It’s almost inappropriately catchy, opening with the plainly devastating admission to feeling stranded in “a place I wake up blushing like I’m ashamed to be alive,” before asking “how long can the world go on under such a subtle god? How long can the world go on under no new word from god?’ in a typical Berman swerve, the song unfolds, sardonic, into the best chorus on the record: “we’re just drinking margaritas at the mall, that’s what this stuff adds up to after all.”

As well as his hallmark dalliance with all things grim and uncomfortable, there are aphoristic moments of a hopeful brighter outlook; “friends are warmer than gold, when you’re old” and ‘Snow is Falling in Manhattan’ is a poetic depiction of gratitude in the continuation of the everyday, how the world rolls on in spite of our personal pain; “the good caretaker springs to action / salts the stoop and scoops the cat in.” Another highlight is the brilliant ‘Darkness in Cold’ which showcases Berman’s wit at its most unapologetically mordant.

Berman is a writer all too familiar with darkness, he confronts loss, inadequacy, failure and grief time and time again but in spite of this, his artistic output – whether in the form of his songs or his equally brilliant poetry, is ultimately optimistic. By the very act of configuring pain into song, Berman demonstrates as candidly as anyone, the true transformative power of music. It might be, as he puts it the “plod of the flawed individual looking for a nod from god” but despite the overwhelming lack of meaning he constantly attests to, Berman’s songs are bolstered by a unique warmth, an outstretched hand, a kind of daring to keep going. Purple Mountains might be an album hewn from sadness, but the result is a moving, important and evocative testament to resilience. Maija Makela