“The way the word ‘empowered’ is used makes feminism more digestible … I wanted to make work that was maybe less digestible.” This was Kim Gordon in conversation with Sinéad Gleeson at Dublin’s Light House Cinema this past July, having launched an exhibition of her visual art at the IMMA entitled She bites her tender mind. Its title is derived from one of Sappho’s fragments, connecting the project to the ancient poet’s evocations of feminine beauty and desire – while also nodding to the broken-down language that has consistently graced Gordon’s own work, in both her coolly minimalist lyrics and the shredded phrases that decorate many of her canvases.

The exhibition summons a sense of dislocation that Gordon appears to find pervasive in American culture today, and in particular that of her home city Los Angeles. Treating the gallery space like the showhouse in an estate, or as a temporary lodging devoid of personal touches (one part of the exhibition is called “Airbnb”; Gordon had lived in one for a time while writing her memoir, 2015’s acclaimed Girl in a Band), she layers eccentricity atop conformity, the surreal atop the marketable. Irreverent critiques of consumerism are spiked with Gordon’s distrust of the version of feminism that has been co-opted by major-name brands in the 2010s, a distrust represented by the gallery’s alienated domesticity as well as her occasional use of women’s clothing as canvas. The prevailing anxiety is that the commodification of identity is complete in the twenty-first century; feminism is manufactured, packaged, and sold to insatiable, endlessly exploitable demographics – a hashtag, rather than a site of political dissent.

This anxiety has been present in Gordon’s music since the beginning of her career; her songs with Sonic Youth and Free Kitten regularly denounced the processes by which women are made to suffer humiliating, dehumanising exploitation. Think of ‘Tunic (Song for Karen)’ from 1990’s Goo, which finds Karen Carpenter singing to her family from beyond the grave after starving herself to death – her peace in the afterlife a wry comment on how sneering dismissals of her work were replaced posthumously by empathy and reverence. Or recall ‘Swimsuit Issue’ from Dirty, where Gordon rages against the ways in which misogynistic media permits men to think sexual harassment acceptable, and sex a commodity to be exchanged for professional prospects.

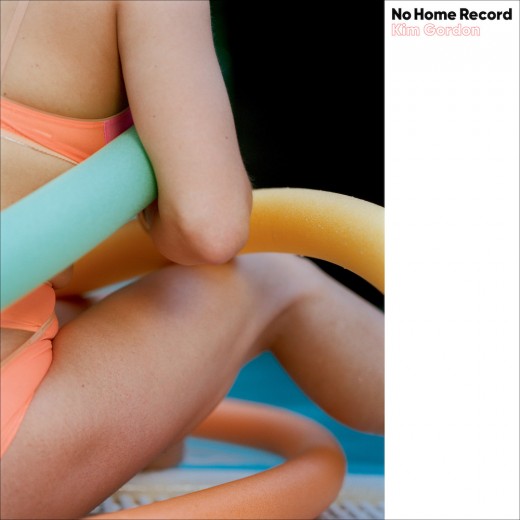

These concerns are very much present on No Home Record, Gordon’s first solo album following post-Sonic Youth collaborations with Bill Nace (as Body/Head) and Alex Knost (as Glitterbust). The record is named for filmmaker Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie (2015), a work that shares Gordon’s interest in scenes of domesticity, and which Gordon seems to have taken as a sort of talisman while creating her current projects. While there is certainly a sense of continuity with her past work, as noted above, fresh influences such as these indicate that Gordon is unafraid of exploring new ways of thinking about identity and consumerism, as well as exploring new idioms in order to express her ideas; nowhere is this clearer here than in her experimentation with new musical terrain.

When it appeared in 2016, the single ‘Murdered Out’ – present here and, as with most of the album, produced by Justin Raisen – marked a sharp departure from Gordon’s previous work, replacing guitar-led abrasion with synthesisers and the clipped, sterile beat of a drum machine. At the time it seemed like an interesting one-off, a droll observation regarding blacked-out cars in Los Angeles teamed with a musical setting that evokes distance, complementing the lyric’s emotional guardedness. On No Home Record this sonic texture is replicated on eight other tracks, and while at times slightly repetitive (Raisen’s bag of tricks doesn’t appear to be all that deep), it’s a fitting backdrop for Gordon’s musings in its marriage of noise and predominantly short-form, pop-adjacent structures.

Links between the record and Gordon’s recent visual work are evident throughout. Second track ‘Airbnb’, sharing its name with the aforementioned section of She bites her tender mind, draws influence from the sense of transience associated with such spaces. It’s an “American idea”, she sings, beckoning the listener to “come on down” for a Malibu getaway, as though she were Annette Funicello inviting us to a beach party – imagery that has captivated Gordon since her childhood in 1960s L.A., when the Beach Boys’ cheery visions of California took grip of the American public’s imagination. But the space’s artificial domesticity is rebuked by the singer with biting irony (“Licensed guest house / For us alternatives”) delivered with vexed gasps and hollers.

The commentary is for the most part humorous, incorporating slogans from advertising (‘Get Yr Life Back’, in which Gordon daydreams about “the end of capitalism” in a yoga class), and pop culture references (‘Don’t Play It’, which references Lesley Gore’s ‘You Don’t Own Me’ in a diatribe against constant self-documentation on smartphones and social media). But the discordant music and typically straining, often atonal, vocals centre her disconcertment regarding the saleability of identity. Her participation in, and benefitting from, said culture isn’t exempt from attack; there’s a ring of self-disgust to songs like ‘Cookie Butter’, with its mocking repetition of the first-person singular. But Gordon never appears sanctimonious, rather angered by how she has been ensnared.

“Digestible”, as Gordon said in Dublin, is what is opposed here; digestible art, digestible identities, digestible activism. With harsh noise, unmelodic vocals, and tattered lyrics, the record continues Gordon’s long project of critiquing corporate expropriation and saleable notions of selfhood. She’s rarely easily digested; she’s always essential listening. Seán Kennedy