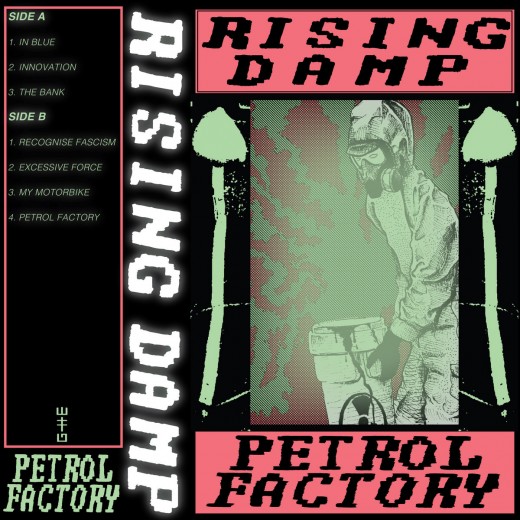

So what exactly is punk? It’s a question that probably goes back at least as far as when The Damned released ‘New Rose’, and tends to get easily muddied in issues of purity and pretension. It was addressed again recently through a tongue-in-cheek, classroom-style approach on Declan Synnott’s Ain’t You on Dublin Digital Radio. While following along with specially prepared Powerpoint slides and track selections from artists as diverse as Special Interest, Rites of Spring, and Dustin the Turkey (!), Mr.Synnott and his class mused on the punk credentials of various topics. And while there were occasional unambiguous declarations (cats: punk, Malcolm McClaren: not punk), the question again proved quite slippy: not being punk is punk, calling something punk that acts punk but doesn’t know what punk is isn’t pun. “It’s complicated”, Synnott points out. Given that putting labels on things isn’t really punk, perhaps it’s best to just let the music do the talking: the oft-vaunted “3 chords and the truth” –though even those 3 chords aren’t strictly necessary. In this spirit, Synnott’s producer on the show, and fellow Bodycam noise merchant, Michelle Doyle puts forward her own thesis in the form of Petrol Factory, her debut album as Rising Damp.

Opener ‘In Blue’ sets the tone for the album. Written around the Belfast rugby trials of 2018, and the sense of injustice at a society where “the right kind of Euro/Buys the right ‘Free to Go’”, Doyle uses her opening shot to take square aim at a neoliberal island that has failed its women. ‘In Blue’ never feels nihilistic, however: with Doyle’s diamond-hard vocals, and the rolling bounce of its bassline and pounding drums bringing to mind an alternate timeline where New Order and PiL took cues from the Melvins. This is not the sound of a person who has given up on change. Petrol Factory is far from being a throwback, but the sounds of the ’80s are one of the more overt sonic frames of reference throughout: jagged basslines, huge sounding snare drums, the weaving of synths throughout traditional rock forms. Given that Ireland has (supposedly) just recovered from the economic fallout of 2008 and with another recession almost certainly around the corner, sounds evoking the time of a populace accused of “living way beyond [their] means” is highly appropriate. Anti-upskilling anthem ‘Innovation’ and its ending refrain of “Fire Everyone” takes on an extra resonance in a post-Coronavirus world. But to focus on the influences of the past would be to do the album a disservice, as that would ignore just how uniquely vital and now it sounds. Take lead track ‘Excessive Force’ for example: the urgency of Doyle’s vocals are driven by EBM pulses and the forcefulness of power electronics but without sounding anything like it, reminiscent of Pharmakon sans the electrical discharge smear.

The sound of the shorter songs on the album are driven by the choice of live instruments, but album centrepieces ‘The Bank’ and ‘Petrol Factory’ flip the script entirely. Between them there is over 40 minutes of electronic exploration. ‘The Bank’ is less a tribute to the former emo hangout, and more a scathing attack on a building and institution so representative of the ever-increasing erosion of dignity in Irish people’s lives: with Doyle’s descriptions of anti-loitering architecture and light and sound specifically designed to repel the young, it’s hard not to see it as a synecdoche for our present moment – a No Wave Reeling in the Years from an uncomfortable current reality that eventually descends into a resonant squall. The album’s closing title track takes a more minimalist approach, updating the abstract dread of Puce Mary with the echoing zeal of fellow Irish experimental outfit Salac at their most atmospheric.

In his exhaustive retrospective Rip It Up And Start Again, Simon Reynolds argues that the real musical revolution could be found in the sense of innovation and forward thinking that crystallised around post-punk developments like John Lydon throwing himself more into his Public Image: “The very prefix ‘post-’ implied faith in a future that punk had said didn’t exist”. Petrol Factory evokes this forward-facing, fiercely innovative spirit and updates it with a specifically modern, specifically Irish context: it is a klaxon-call from a terrifyingly, thrillingly open future. After all, in order to build a new world, some old things will have to get destroyed. In the words of Vicky Langan: Rising Damp for anarcho-Taoiseach!.Will Abbott