Beethoven branded Don Giovanni as frivolous, but as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote in a letter to his father in 1781: ‘For do you really suppose that I should write an opera-comique the same way as an opera-seria?’

For Mozart, Don Giovanni was an opera-buffa, though the much darker tones that underlie the comedic shenanigans make this an oddly complex psychological opera. This Northern Ireland Opera production wholeheartedly embraces the playfulness of Lorenzo da Ponte’s libretto.

And, with a Titanic-esque luxury liner providing the setting for the unfolding action, complete with icebergs in the distance, it’s hard not to imagine that this is Director Oliver Mears’ way of saluting Belfast before his move to The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden next year.

For a full six minutes the Ulster Orchestra, under Nicholas Chalmers’s baton, fill the Grand Opera House with the strains of Mozart’s stunning overture. The score is a portent of Don Giovani’s stormy adventures to come, and laden with the galloping drama, jocularity and sweeping lyricism that are the hallmarks of this ever-popular opera.

Mozart apparently wrote the overture after midnight on the eve of the Prague premier in October, 1787. The composer was renowned for leaving the overtures to his latter operas until the eleventh hour, probably out of a theatrical sense of showmanship, but it’s more believable that he already held the score in his head.

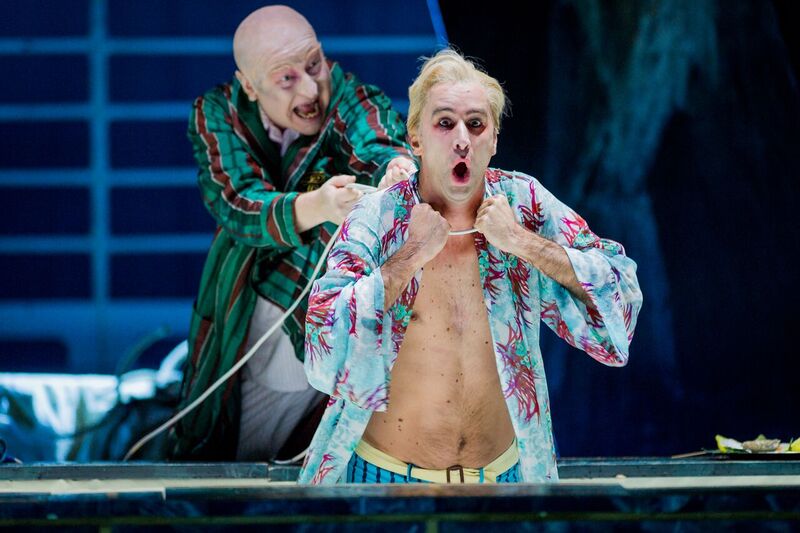

Henk Neven is superb as the rakish, womanising Don Giovanni. From the attempted rape of Donna Anna (Hye-Youn Lee) and subsequent murder of her father, the Commendatore (Clive Bayley) at the beginning of Act 1, to his attempted seduction of anything in a skirt, Neven incarnates the lustful, amoral yet charismatic Don Giovanni with equal measures of élan and nonchalant swagger.

Donna Anna and her betrothed Don Ottavio (Sam Furness) swear revenge, and the plot, simple as it is, is henceforth in full swing.

John Molloy as Leporello, Don Giovanni’s long-suffering yet opportunistic servant, is equally persuasive. Led a merry dance by his boss’s sexual predatory instincts, Leporello seems as captivated by Don Giovanni’s magnetism as the women his boss ensnares, though not without internal reservations.

On hearing a crying woman Don Giovanni remarks: ‘Poor girl! Let us try and console her grief.’ To which Leporello remarks in an aside, ‘Thus he has consoled eighteen hundred.’

Producing a hefty black ledger – no little black book for the Don – Leporello lists to Donna Elvira (Rachel Kelly), another spurned lover, Don Giovanni’s conquests: in Italy, six hundred and forty; in Germany, two hundred and thirty one; a hundred in France; in Turkey, ninety one; in Spain, already one thousand and three.

The last number Leporello repeats several times, with only lightly disguised relish.

Don Giovanni, we learn, has seduced maidservants and princesses, peasant girls and baronesses – women ‘of every age, every class, every shape and every size.’ It’s a slight change from the original libretto, which mentions also ‘of every age’ – a concession perhaps to these politically correct times?

Surely not, for Northern Ireland Opera has been anything but prudish under Mears direction and a procession of women from diverse social backgrounds – a coke-sniffing hooker, a schoolgirl {‘still intact’) and a woman with a walking cane, so long in the tooth that she’s bent double – file into one of the ship’s cabins – a likely metaphor for Don Giovani’s ledger.

Other small liberties are taken with the libretto, with some of the recitative from Act II cut altogether. This is a good move, as the sung-spoken text, to the constant punctuation-like accompaniment of harpsichord, is lengthy enough.

Then again, the wonderful arias are framed by the recitatives, the contrast between relatively mundane commentary and sparkling solo, duet and ensemble performances – buoyed by the Ulster Orchestra – being marked.

Applause from a packed Grand Opera House greets one penetrating solo spot after another.

The narrative unfolds against the backdrop of Annemarie Woods’ imaginative set designs – bustling quayside, ship-deck, ballroom, cocktail bar, swimming bath and those private, ship cabins, ever full of intrigues, which provide a feast for the eyes.

The bonhomie of the pre-wedding party of chef Masetto (Christopher Cull) and chambermaid Zerlina (Aoife Miskelly) – whom Don Giovanni does his level best to seduce – contrasts with the decadent feast thrown by Don Giovanni and Leporello, where wild, spear-carrying men and scantily-clad women in Carmen Miranda fruit-hats cavort while Don Giovanni snorts a line of powder off a woman’s back.

Opiates and cocaine were popular drugs in Victorian Britain, and were considered as recreational habits and not addictions, a view certainly shared today by a certain segment of Northern Ireland’s weekend-partying youth.

Carnival-esque debauchery dovetails with the steely wings of revenge as the various vengeance-seeking circles close around Don Giovanni. Masetto enters the cocktail bar with a posse of the kitchen hands bearing a gruesome array of weapons with which to peel, scrub, roll, cube and dice Don Giovanni to death.

Don Giovani, however, beats seven shades of tiramisu out of Masetto and lives to philander once more.

A fantastical, supernatural ending sees the ghost of the Commandatore return – preceded by a statue crashing through the wall – to strangle Don Giovanni with a hairdryer cable and then electrocute him to death in the swimming pool.

The liberally interpreted tragi-comic end that Mears’ directorial hand metes out to Don Giovanni strays from the original libretto – where Don Giovanni is consumed in the flames of hell – but not from the overarching spirit of Mozart and da Ponte’s work – humorous yet slightly disturbing.

The gravitas of such rough justice, nevertheless, is captured dramatically enough in the powerful musical finale.

The cast throughout is uniformly impressive and individual musical highlights – at least a dozen wonderful arias – are simply too numerous to mention. No less impressive are the layered exchanges, the duets and trios, where lines interweave in exhilarating sonic tapestries, or the potent ensemble choruses. Not for nothing does Mozart’s Don Giovanni remain one of the most widely performed and popular of all operas, nearly two hundred and thirty years on.

The audience is generous in its applause as the cast takes its bows. There are cheers too for Mears and his outstanding creative team, who take several well-earned bows.

In little more than half a dozen years Mears has put Northern Ireland Opera on the international operatic map. Equally, the company has established opera as a core part of the local cultural calendar, which is no small feat. This, NI Opera has achieved not by playing it safe, but by taking risks.

Whoever follows in Mears’ footsteps as Artistic Director of Northern Ireland Opera will inherit a progressive, modern opera company of bold artistic vision – one that dares to challenge convention. This perhaps, is Mears’ greatest legacy. Ian Patterson

Photos by Robert Workman