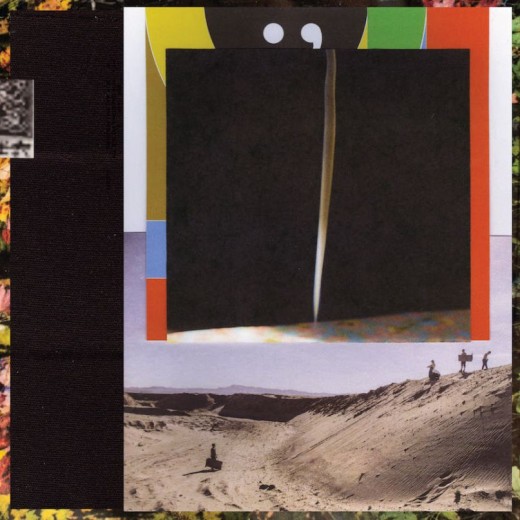

Justin Vernon has written his most personal work in isolation, secluded in a cabin in Northern Wisconsin. In the span of 13 years, the Bon Iver project has empowered him to map his personal growth, archive periods of stress, and mediate addiction and trauma. The fourth iteration of this journey, i,i, reflects on the duality of the self as it navigates a turbulent political landscape. The inner and outer worlds communicate here, and seek to find peace.

The band embraced a dramatic move towards experimentation on 2016’s 22 A Million, producing some of their most urgent and effective work. Here, the urgency remains, but is subdued somewhat by a stronger clarity of purpose in the artist’s inner life. The lyrical world of the album is more accessible than before, and the urgency of the wider political world undercuts the journey at crucial moments.

‘Hey Ma’ evokes the For Emma, Forever Ago era, with Vernon’s falsetto serving as the centrepiece, supported by rich nostalgia-soaked instrumentation. Balanced within this sound are periodic moments of glitched vocals and electronic beeps – the 22, A Million learnings somewhat more subtle now – harmonising Vernon’s personal domain with the outer, now more troubled world. Addressing both the climate crisis and the immoral exploitation of natural resources for profit while evoking the mother-child relationship is something that Vernon can only get right following the experimentation of his previous work.

The same goes for ‘U (Man Like)’, with its cutting portrayal of opioid addiction and wealth disparity in modern America underscored by rich, soulful piano and sonorous vocal harmonisations. ‘Sh’Diah’, too, works as a mood piece, sombrely recounting the day following the 2016 presidential election. Lyrically it’s abstract, but there is pain pouring from the soulful, mourning brass. What can be said about this, ‘the shittiest day in American history’ that hasn’t been said already? What remains is a feeling, tenderly explored through the expressive, lamenting sax reaching for harmonic resolution but never truly finding it.

There is real growth here — signs of an artist not only reflecting on the world around him, but the learnings of the self that have guided him towards understanding it, or at least coming to terms with his place within it. i,i suggests a newfound clarity of purpose for Vernon. Where despair and fear reigned on 22, A Million, hope springs eternal here. There is comfort in withdrawing, from time to time, from the news cycle. We know this already, but it is powerful to witness Vernon give himself permission to hope. We “run and hide for a verified little peace” but “sunlight feels good now, don’t it?”.