As Hawkwind’s first four years on record are collated on a new 11cd boxed set, This is Your Captain Speaking… Your Captain is Dead, Steven Rainey delves into the murky world of space rock, and discovers much more than simply a band responsible for unleashing Lemmy on the cosmos.

At the end of Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, astronaut Dr David Bowman is pulled into a vortex, going on a journey into the infinite, a kaleidoscopic assault on the senses that could mean everything or nothing. Both Kubrick and writer Arthur C. Clarke weren’t exactly in hurry to explain it, and for audiences, a lot of the meaning of that final part of the film comes from the music, a cacophony of voices arranged by Romanian composer Gyorgy Ligeti. The film remains a cultural milestone, and like all great cultural milestones, it has been plundered many times over by rock and roll.

Indeed, there’s long been a suspicion that Pink Floyd’s second album, A Saucerful of Secrets was originally envisaged as a soundtrack to Kubrick’s ‘Stargate’ sequence. Whether there’s any truth in that or not, it makes an intriguing proposition, Pink Floyd’s outer space musical explorations melding pleasingly with Kubrick’s voyage into the stars. But whilst Floyd missed their chance, and settled for scoring abstract French New Wave films, a band formed in London the year after the film’s release that would have been perfectly qualified to tap into Kurbick’s psychedelic mayhem. They were called Hawkwind, and over the next 40 years, they would voyage where few bands would dare. Frankly, not many would even want to.

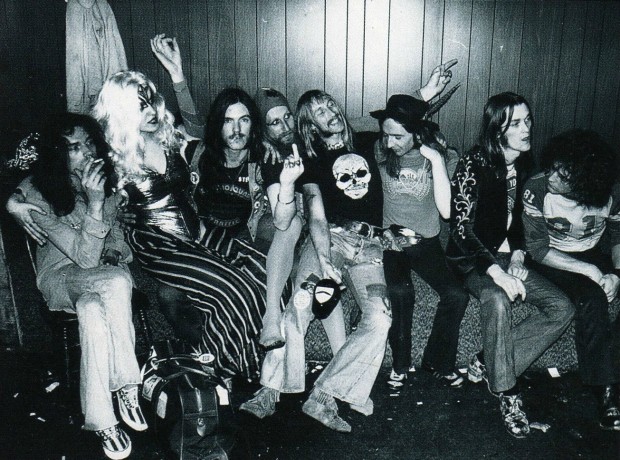

Despite being a roving gang of psychedelic warlords, Hawkwind are very much a product of the time they lived in, emerging at the tail end of the hippie dream, and initially finding favour with the tired stragglers still holding on to the dream. In the early days, the band would become a mainstay of free festivals, communes, and numerous benefit gigs. In a sense, Hawkwind was as much a way of life as it was a band, attracting a motley crew of burn-outs, artists, writers, free thinkers, and weirdos as they travelled.

By the time of their 1970 self-titled debut album, they were a six piece, centred around guitarist and vocalist Dave Brock, saxophponist and flautist Nik Turner, guitarist Huw Lloyd Langton, and Dik Mik on synthesiser. The record is a strange mixture of folky ambience, weird atmospherics, and psychedelic rock. That idea of the band as a travelling caravan of misfits resonates with the music, as the band deliver a competent, if ultimately uninspiring mish-mash of styles and ideas. However, one thing unites the songs and points forward to the next step in the band’s evolution: the howling, dissonant wail of Dik Mik’s electronic experiments.

‘Synthesiser’ is a strange word, conjuring up a myriad of meanings, depending on the time and context that one relates it to. The 80s? Of course, it’s all New Romantics and synth pop bands, plastic sounds and plastic clothes. The 21st century? Well, that could be pulsing sequencers, it could be washes of ambient sound, or it could be whatever you want really. Back in the 70s, it tended to mean a man (probably Rick Wakeman), wearing a cape (definitely Rick Wakeman), firing out solos and arpeggios as fast as his fingers would allow (It’s Rick Wakeman, dude. Believe me). But for Hawkwind’s Dik Mik, it meant an opportunity to conjure otherworldly sounds, swirling eruptions of sound that cut through the sound of the band, slashed apart the music, and threatened to overwhelm it. And once the gears locked in place, it sounded like absolutely nothing else on the planet. Or any other planet, for that matter.

1971’s In Search of Space finds Hawkwind taking the first step on a journey into the otherworld, a milestone that essentially coins the term ‘space rock’. Key personnel have been added to the crew: sound engineer Del Dettmar helps out on the synths, and poet Robert Calvert and graphic designer Barney Bubbles contribute ideas, writing, and art for the sleeve, helping build a concept around the album. No longer are Hawkwind a band, now they are voyagers, with In Search of Space itself becoming a ship containing two-dimensional intergalactic beings.

The music contained aboard the ship captures Hawkwind cementing their key sound, droning, repetitive, howling noise, thrillingly nailed to a propulsive rock beat. Songs like ‘Master of the Universe’ and ‘You Shouldn’t do That’ largely ignore conventional song structure, but don’t quite fit the mould of the American psychedelic improvisers either. German bands like Can and Amon Dull were forcing their music further outside the realms of possibilities at the same time, but they still sound like humans in a studio, or on a stage, playing music. Hawkwind were more like a bunch of druids conducting an arcane ritual, an idea that would take on even more resonance as the years went by.

But first, the inevitable hit single – enter Lemmy.

After a number of changes to the rhythm section, Ian ‘Lemmy’ Kilmister joined the band on bass, whilst Robert Calvert graduated to occasional vocalist and songwriter. One of their first real contributions to the band was a rock and roll boogie all about space travel (unsurprisingly) which Calvert sang. Deeming the original vocal to be too weak, and with Calvert temporarily sectioned as a result of his bi-polar disorder, Lemmy steps up to the mic, re-records it, and Hawkwind end up having a hugely unlikely hit single with ‘Silver Machine’.

The song has an ageless charm, still sounding like little else, largely due to the continued (over)use of Dettmar and Dik Mik’s synths. Lemmy’s vocal is classic Lemmy, and the whole thing sounds crazy in the context of 1972 pop music. Quite what Donny Osmond, David Cassidy, and the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards thought of the song at the time remains unrecorded, but it put Hawkwind on a mainstream footing, and now that they were there, they – if anything – upped the ante on their intergalactic voyage.

Doremi Fasol Latido is another quantum leap forward after In Search of Space, Lemmy and new drummer Simon King instantly making an impact, with tracks like ‘Brainstorm’ and ‘Space is Deep’ possessing a muscular girth that had previously been lacking, whilst Dave Brock’s guitar sounds grittier and nastier than ever. This is primal music, a dark, mysterious creation that sounds like it is being willed into existence, rather than being played. Like hurtling into the heart of a black hole, Hawkwind were hammering their music as hard as they could, and the results are thrilling.

The stage was set for Hawkwind’s magnum opus, the final position in the crew being filled by fantasy novelist Michael Moorcock. His ‘Elric’ novels are like a mixture of JRR Tolkein and Conan the Barbarian, and with Brock already drawing lyrical inspiration from his writing, it seemed natural that he should collaborate directly with the band. Despite the continuing evolution of the band’s studio albums, it is the live stage upon which they craft their dark arts, and suitably enough, their next project captures them in full flight, tying together every cosmic strand they have thus far created. The pulsing and howling electronics, the earth shattering bass, Nik Turner’s shimmering, ethereal woodwind, Calvert’s daemonic poetry, and booming intonation, Barney Bubbles’ increasingly elaborate and labyrinthine design work, and the carnival of dancers and performers that surrounded the band – they all meld together in the heart of the Space Ritual.

This double live album is simply one of the greatest documents of a band on stage, with Hawkwind positively tearing the fabric of reality apart in front of an audience in Liverpool and Brixton. Barney Bubbles, by now a crucial part of the band, rather than merely a graphic designer (he would later go on to provide classic sleeves for Elvis Costello, Ian Dury, and the Damned), had constructed an elaborate stage set, which not only involved a liquid light show and stage props, but involved intense discussion as to the ideas behind the designs, the significance, the history, the spirituality, and the metaphysics.

The show was largely drawn from the Doremi Fasol Latido material, but given a thorough overhall, confirming that the stage is where Hawkwind truly came to life. Calvert comes into his own, intoning Moorcock’s apocalyptic visions, whilst all manner of sonic cacophony erupts behind him. But beyond the atomospherics, and Turner’s spacey sax and flute, Hawkwind exert real muscle, proving what a formidable rock band they could be, Lemmy’s bass pummelling Brock’s guitar to create slabs of molten riff. Space Ritual is easily Hawkwind’s greatest triumph, and stands as one of the finest live albums ever made.

After such a definitive statement, there’s not really too much else to say, but Hawkwind continued saying it for another four decades. 1974’s Hall of the Mountain Grill is another strong album, but one can sense the engines of starship Hawkwind beginning to malfunction. Whereas previous albums all built upon the success of the last, and pointed the way towards the future, Hall of the Mountain Grill cleans up the sound, sounding like a conventional prog-rock album, albeit a very, very good one. ‘The Psychedelic Warlords (Disappear in Smoke)’ is one of their best songs, a driving, hard riffing beast that snarls and growls more than they had done in the past, but ultimately the album feels like an afterthought when compared to Space Ritual.

In the years that followed, Lemmy would be ousted (for being caught with “the wrong kind of drugs”, according to him), Barney Bubbles would fall in with New Wave label Stiff, and create some of their most iconic imagery, Turner would get sacked for playing over the rest of the band, returning briefly in the 80s, and eventually only Dave Brock would remain, pushing out new product with a machinelike regularity. There’s still gems to be found in the post 1974 years, but the glory days were over.

In hindsight, it’s perhaps predictable that Lemmy would go on to have more success on his own than with the band. After all, he’d been the voice of their one bona-fide hit single (the follow up to ‘Silver Machine’, the Calvert sung ‘Urban Guerilla’, scraping into the top 40, but hampered by being released in the midst of an IRA bombing campaign, and featuring the chorus of “I’m an urban guerrilla, I make bombs in my cellar.”). After a few years in the wilderness, he returned with Motorhead, ditching all the spacey cosmic elements of Hawkwind, distilling it down to the pure guitar, bass, and drums attack of the Space Ritual era, and managing to successfully appeal to both metallers and punks.

But between 1970 and 1974, as This is Your Captain Speaking…Your Captain is Dead ably proves, Hawkwind journeyed further out than anyone had ever dared, and very few have ever managed to attempt this level of cosmic exploration since. If they once journeyed in search of space, their only real failing was that they actually managed to find it. Steven Rainey