‘Earth receive an honoured guest..’ The opening of Auden’s famous tribute to Yeats, with its distinctive rhythm which Heaney dubbed ‘Wystan Auden’s metric feet’ seems appropriate as the poet makes his final journey back into the landscape that inspired so much of his best work. For Heaney was a poet formed out of the claggy clay of his home, not just an Irish poet, or a Belfast poet, but a mid-Ulster poet. In his work I recognise the expressions and above all the accent that I grew up with, its mix of the clumsy and the lyrical, ‘demesnes stalked out in consonants’, flooded by the locals’ ‘vowelling embrace’.

The poem ‘New Morning’, from which these lines come, first appeared in Heaney’s third book ‘Wintering Out’, an underrated collection which appeared in 1972 and contained Heaney’s initial reaction to the outbreak of ‘the Troubles’. It is important because within it he lays down a manifesto possible only through an embrace of the possibilities of the poetic imagination. At the height of the Troubles, Heaney the visionary was already anticipating our slippery peace. The link between landscape and language is even more explicit in ‘Anahorish’ from the same collection ( ‘soft gradient of consonant/Vowel meadow’ ). It’s as if the poet was rolling the words around his mouth like a fine wine.

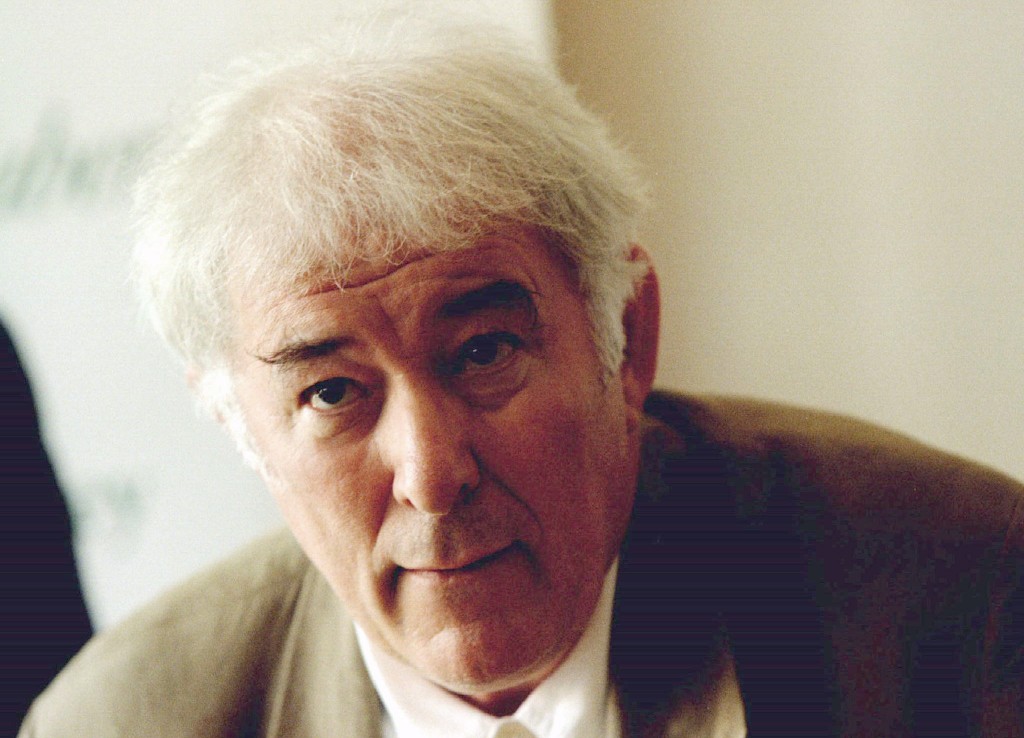

But the sense of a new and distinctive voice emerging to bring the world such local cadences was intoxicating. And especially to readers like me for whom their musicality was lost by virtue of their sheer everydayness. So as Seamus Heaney’s international reputation grew, for us he was still the town poet. Stories of his accessibility are legion, and mine is no exception. After doing a reading in the Arches bar in Magherafelt, and on learning I was doing a Heaney based project at university he sidled over and listened patiently as myself and my brother regaled him with abstruse theories comparing him to Van Morrison. The half filled glass of Smithwicks remained unsipped out of, I suppose, an unwillingness to seem uninterested.

One of the things he read that night was an extract from his forthcoming ‘Station Island’ collection, a pointed in memoriam about a neighbour killed by gunmen impersonating police officers. The poem from which it emerged, his long Dantean pilgimage to Lough Derg, filled with characters both from his past and his reading, is arguably his greatest use of that distinctive ‘South Derry timbre. It’s filled with local expressions and a wry, understated humour. He notes ”Of course, some came here on the hunt for women’ but the closing exchange with the spectre of James Joyce implies a definitive break with the past (‘Let go, let fly, forget).

Seamus Heaney’s modesty was no act but he had a proper awareness of his stature. So when, in his Collection ‘Spirit Level’ he made public his run-in with a republican who demanded ‘when are you going to write…something for us’ it was a clear declaration of artistic independence. The burden of expectation might have lessened with the winding down of the Troubles, but the times still required a different kind of spokesman. Heaney was now the perfect example of someone who was the ideal unifying figure. Northern, but based in Wicklow, popular both in Britain (where a poet laureateship was briefly mooted) and worldwide. ‘The forgiving tone in poems like ‘Mint’ with the line ‘Yet let all things go free that have survived’ spoke of a burgeoning optimism fostered by the ceasefires. Within that context a Nobel prize in 1995 was as inevitable as it was deserved.

I would argue that Heaney’s international reputation lies not just in his ability as a poet but in the unique way he carried his landscape within and translated it to the world. Latterly he had been returning to it, as evidenced by his wonderful collaboration with Denis O’Driscoll in ‘Stepping Stones’ , proving he was also no slouch when it came to prose. In his acclaimed, now apparently final collection, ‘Human Chain,’ one of the poems (Route 110) follows the the old bus route from Belfast to Hillhead and Castledawson. Like ‘Station Island’ it has a mythical link, this time to Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’. If a journey can describe a lifetime, this one surely does with its evocation both of Heaney’s father and its final triumphant welcome of his grandchildren whose ‘long wait on the shaded bank has ended’. It acts as a kind of reverse epitaph and has become all the more moving now.

Heaney was scheduled to give the opening talk at the forthcoming ‘On Home Ground’ poetry festival in Magherafelt. The yawning gap now left there echoes the chasm his leaving has left in our own culture. For those who took up a pen to write in his shadow, he was and remains the boss of us all. Michael Conaghan