In Diamond Dogs, with a twisted and sophisticated take on his sound, David Bowie predicted a dark, post-apocalyptic future world. 40 years on, how does the prophecy and the music stand up?

In 1974 David Bowie needed to deliver. The Ziggy Stardust album (1972) and accompanying stage show was a whirlwind success and saw Bowie become a significant rising star in America and the most important pop artist in the UK. The follow up, Aladdin Sane (1973), was swallowed up as a straight sequel by a public so Ziggy hungry, they barely noticed the (subtle but not insignificant) musical developments. In time for the Christmas market of the same year, came a covers album. Pin Ups now seems (and can’t have seemed much differently at the time) like a cash in and a stop-gap to allow Bowie to plan his next move. That next move would come under more comprehensive scrutiny than anything he’d released before, hence the need to deliver.

As Pin Ups hit the shelves, whatever careerist thoughts people might have had about him, Bowie’s concerns were of firmly of an artistic bent rather than fiscal. Renowned (and often reviled) for his magpie-like borrowing from a broad palette of influences, in late ’73 his latest obsession was the “cut-up” style of the beat poets and of William Burroughs in particular. The technique (taking a finished piece of text, cutting it to pieces and rearranging it to form a new text) formed a notable lyrical tool in the writing of Diamond Dogs. Musically, having perfected (if not exclusively invented) glam rock, Bowie was keen to move on before it became stale which of course it soon would. While he managed to thoroughly update his sound in parts of the album, elsewhere it linked directly back to Ziggy setting up a strange duality. Conceptually though, Diamond Dogs is solid, which cleverly pulled the diverse elements together. The concept, as we’ll see, may have been second hand (and on closer inspection feels slightly less than watertight) but nevertheless, it works.

The concept is derived from another of Bowie’s literary favourites – Nineteen Eighty-Four. Diamond Dogs actually began life as prep work towards a stage musical of the George Orwell dystopian classic. This planned theatre version was abandoned for a number of reasons (not least because the rights were denied) but Bowie took the material he’d written and applied it to his own nightmarish vision. Set in Hunger City where “Fleas the size of rats sucked on rats the size of cats” Bowie conjures sinister images of a land not for the faint hearted.

‘Future Legend’ gets the fun started coming across like a movie trailer that begins “In a world…” He introduces us to, and skillfully engrosses us in this frightening landscape in a brief tableau. With just a few monstrous lines of cut-up narrative backed by appropriately spooky tunage, the scene is well and truly set. It’s grim and yet it’s grotesque camp too. Then, just as we’re ready to be sucked into this decaying universe, the ghost of Ziggy appears and blasts us with the title track. “This ain’t Rock ‘n’ Roll – This is Genocide” he warns with a sound-bite proclamation. It makes the intro feel like a trick, yet the familiar glam rhythm is still gratifying and the sound – The Stones fronted by Iggy (or Lou, or both) is even more so. The cut-ups continue and map out the story successfully. Although it sounds like Ziggy, he does introduce us to new persona Halloween Jack, who inhabits this realm and despite it’s hazards, apparently thrives there.

At this point the album can go either way. Apart from that weird intro it’s Bowie business as usual (Ziggy was dark too remember). It’s here that Diamond Dogs begins, in earnest, to nail it’s colours to the mast. An almost nine minute suite ‘Sweet Thing/Candidate’ lays it on thick and challenges us to get on board or run. It’s an immense psycho-ballad affair that introduces Bowie’s throaty baritone. It’s the vocal style that was to galvanise so many goth rock singers over the following decade but through the song it progresses gradually upwards reaching falsetto and somewhere beyond. It’s an heroic singing performance rarely matched (though he would come close – appropriately on ‘”Heroes”‘). The music shifts throughout from a sluggish fuzz (that Zappa would soon add to his canon) via a late Beatles guitar solo and on through to a kind of art musical that Queen would have come up with if they’d tried.

It’s a lot to take on board which is probably why we’re thrown straight back into familiar territory with the irresistibly glistening riff of ‘Rebel Rebel’. Then or now, anyone who struggled through the enormity of the preceding nine minutes can relax again with light relief. Released as the lead single prior to the album, every listener was and is familiar with ‘Rebel Rebel’. It’s slithering lead guitar figure is heaven sent and Bowie flaunts his Jagger knock-off even more than on ‘Diamond Dogs’. But that previous nine minutes changed everything and ‘Rebel Rebel’, hardly prone to criticism as a pop song, already feels lightweight and throwaway. So as side one closes we’re at another crossroads. This album can still go either way.

Turning over, unexpectedly it’s the backwards looking Bowie that seems determined to lay claim to Diamond Dogs. ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll with Me’ is an over-the-top uber-ballad that out-glams and out-Ziggys practically everthing from the Stardust era. The vocal delivery, the subject matter, the chord progressions. Every note, every inflection, they’re all straight from the glam anthem text book. To this end, it is close to faultless yet it seems a step backwards, from even Aladdin Sane. However, it becomes apparent that it is at once a hint of things to come (the following year’s soul soaked Young Americans album) as well as a fitting farewell to glam. For from this point on, it is truly Diamond Dogs all the way.

While the suite on side one is an obvious centrepiece of the album, it’s ‘We Are the Dead’ that represents it’s essence most succinctly. An eerie verse manages to maintain an air of semi-positivity, but soon deteriorates into an ever-spiralling nightmare of the most frightful cut-ups yet. The music isn’t completely without precedent (he came close on 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World album) but more than ever before, a haunted house atmosphere prevails. Unidentified ooze drips from every instrument and Bowie sneers through gritted teeth. Hunger City, in all its grime, urban decay and scavenging is brought to life, if you allow the jumbled lyrics to dictate their own meaning.

Should you find Bowie’s borrowing of ideas bothersome, you might want to step out for ‘1984’. It’s a careful reproduction (barely concealed theft) of Isaac Hayes’ iconic ‘Theme from Shaft’. However, once the overfamiliarity of the wah-wah guitar and swooping strings fades, the reshuffled stylistic ingredients do result in a fantastic end product. It is outlandish, theatrical drama, furthers the dark tale, maintains a continuing sense of dread and still features the art-musical feel of the newer sounding material.

And then, much more suddenly than the first, side two approaches it’s finale. ‘Big Brother’ paired with it’s garbled, anti-loop coda ‘Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family’ provide another suite-like section to draw this gruesome tale to a close. The two together only total 5+ minutes, but the unconventional patchwork structure of ‘Big Brother’ and the mis-stepping, yet edgily hypnotic swirl of ‘Chant’, create the illusion of an eternity enduring Bowie’s dark vision. ‘Big Brother’ musically manages to summarise Bowie’s career to date, yet perhaps pushes forward more than anything else here. ‘Chant’ meanwhile is a repetitive experiment in unusual time signatures that oddly compliments the intro, bookending a challenging and rewarding experience.

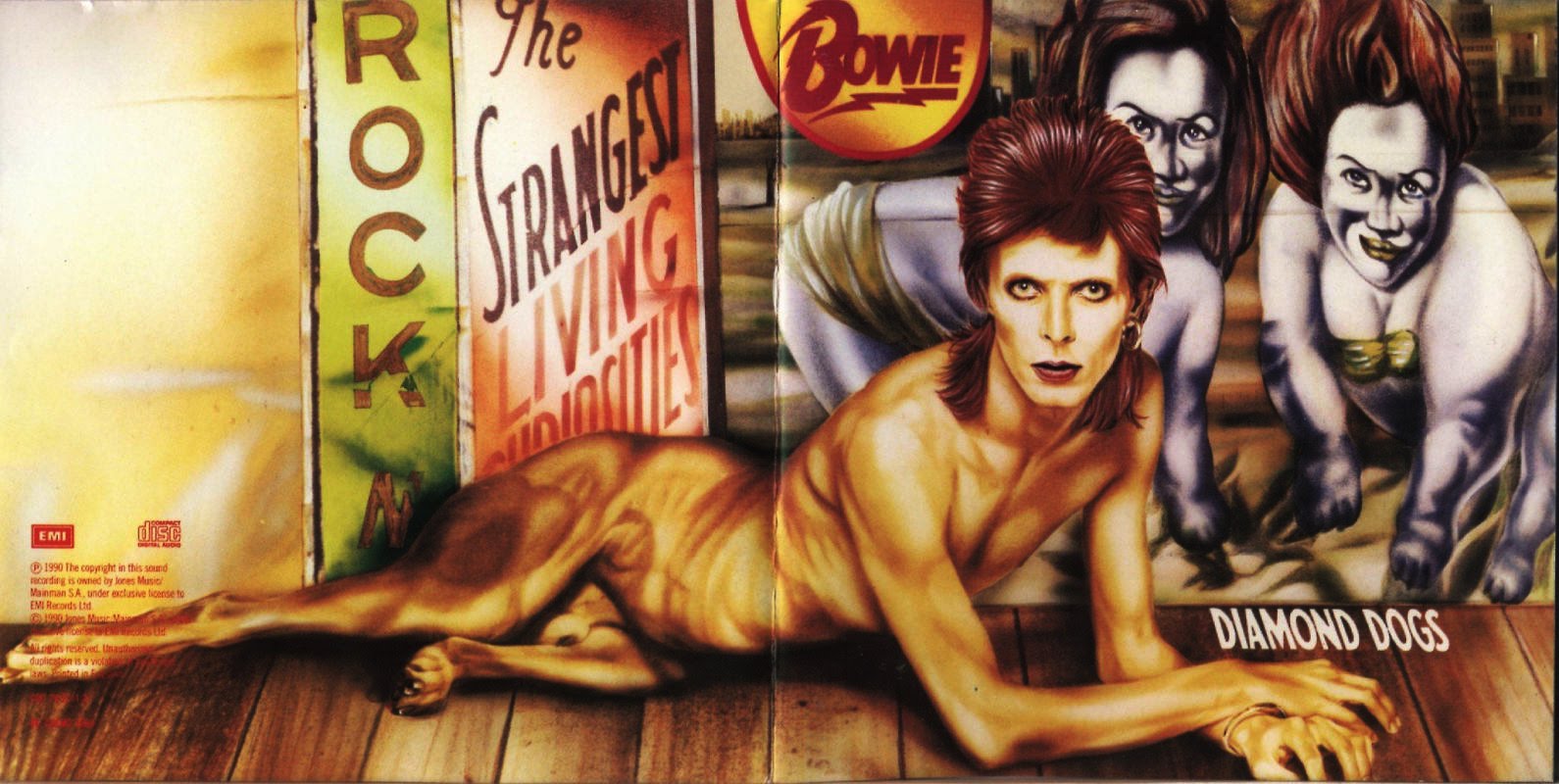

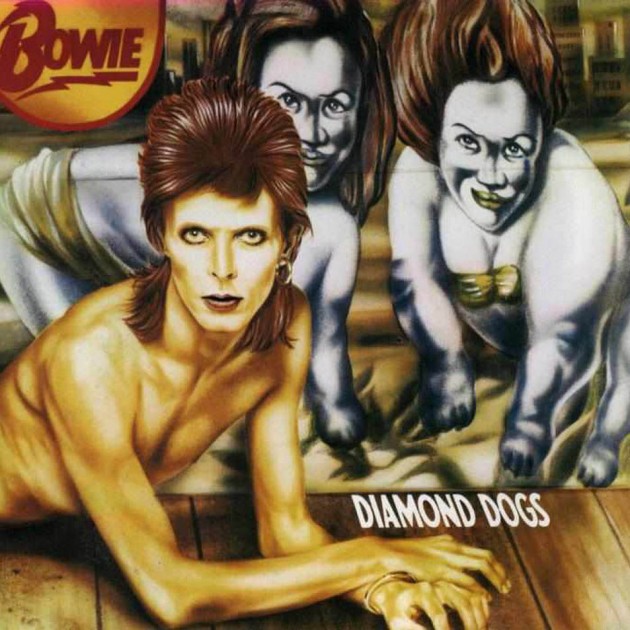

Diamond Dogs was another triumph in a decade of albums few can rival. It’s not perfect. The success as a conceptual whole, illustrated perfectly by the freakish cover art, harshly exposes the more pop moments of the album. The need to include “hits” dilutes the bigger picture. Also the song programming is a touch confused and delays the impact of what this thing is really all about. Ultimately though, these flaws do little to damage the achievement. Artistically, Bowie was moving too quickly for the public, the music industry and even for himself. Jonathan Wallace