Mark Hollis sits alone in his front room. He is tall, shaggy haired and slightly stooped. Frameless glasses are perched on the tip of his long nose as he flicks through a library hardback on the workings of the inner ear. In the corner of the room is a piano draped in grey oil cloth. It resembles a stunted pygmy elephant with unnaturally dainty feet. The piano is covered with books and the books are covered with dust. Hollis hasn’t played it in years, in decades. Not since he perfected music, in fact. Not since he finished it.

Mark Hollis was once the singer for a pop band named Talk Talk. He appeared on Top of the Pops wearing make-up and white pleated trousers, while wallies in moon-boots and mullets kicked balloons about and stealthy sex offenders grappled with teenage girls and be-afroed microphones. Talk Talk were not cute and acutely self-conscious. They were pretty bad pop stars but they wrote pretty good pop tunes so on the whole things evened out for a while. They sold a few records and had a few hits before chart success petered out in the mid eighties. This is not the Talk Talk we are looking for.

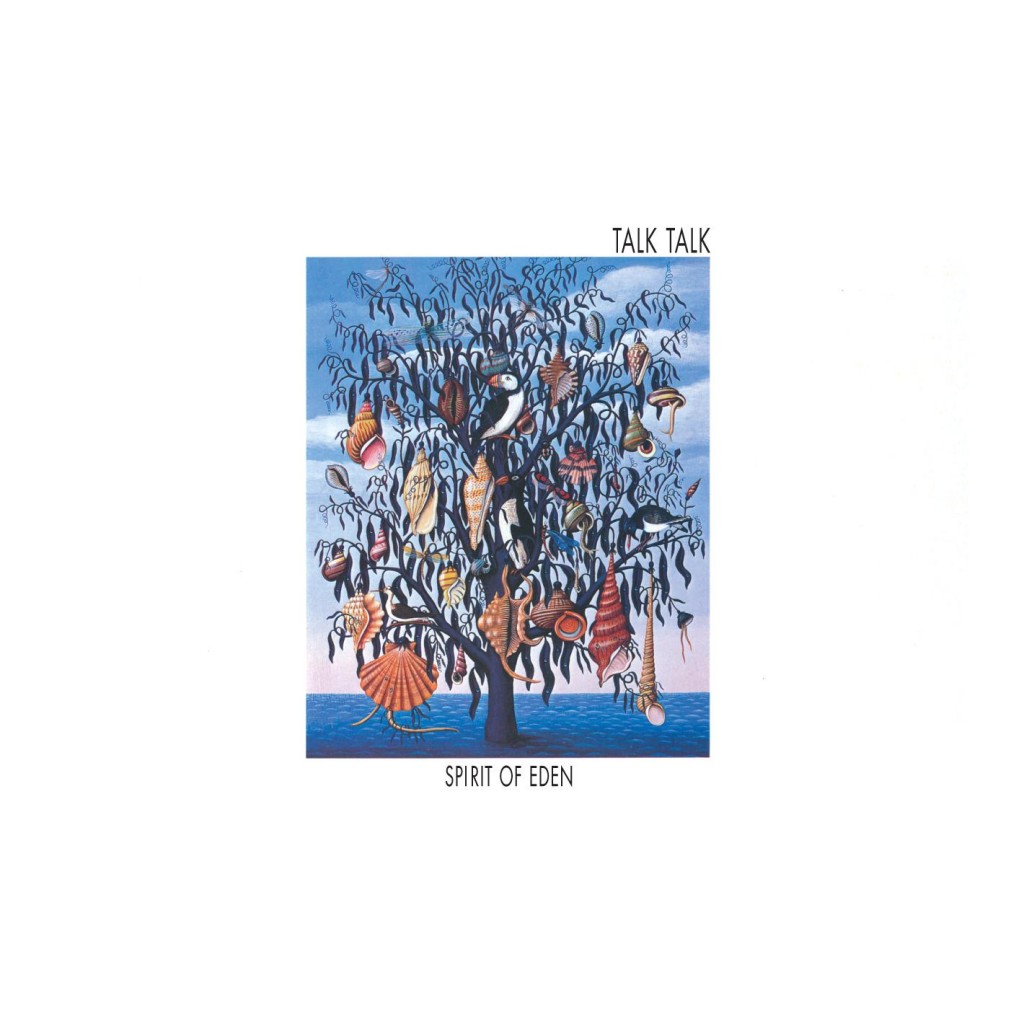

Mark Hollis was also the singer in a very serious musical project called Talk Talk. He sang unintelligible words in an anguished falsetto and was photographed hiding behind his hair in high contrast black and white, usually in the Melody Maker. Rumours abounded about peculiar recording techniques: session musicians trooping through a blacked out, bomb proofed studio, endlessly improvising on nothing, only to have the tapes wiped at the end of the recording and being paid off, while Hollis sat behind soundproofed glass in a haze of dope smoke and patchouli oil. And, of course, all of these rumours were entirely true. These were the circumstances leading to the creation of rock/pop/what?’s high watermark album, Spirit of Eden.

Talk Talk’s story is the inverse of every pop story you’ve ever read. Pop bands start out with the thing that makes you love them. They blurt it all out in an exciting, rough and ready tumult. The first album is the album they’ve been waiting their entire lives to make. They consolidate that sound on a slicker, more expensive sounding second album, which necessarily feature songs about the anonymity of hotel rooms and the misery of endless empty sexual encounters. Then they begin a slow, sorry decline into self parody, complacency and intellectual middle age spread (bands age in dog years).

Talk Talk bucked the trend, evolving instead of devolving, becoming so much more than the sum of their parts by the expedient of gradually jettisoning those parts until only Hollis remained, abetted by Johnny come lately co-pilot Tim Freiss-Green, whose grandfather didn’t invent cinema. The pair of them set adrift in space, grabbing at nuggets of musical notation, snippets of sound, weaving a new musical universe strand by strand. They called it Spirit of Eden. This isn’t what it sounds like.

There is a rasp of harmonica, the portentous swelling of an orchestra, a cetacean cello, moving under the waters. The first two minutes of Talk Talk’s defining album are lurching blur, the sound of a rolling behemoth nudging the surface tension. Everything is, to coin a phrase, flux and mutability. It takes the certainty of a guitar clang and the return of that abrasive harmonica to summon the drums into existence, but there they are: wooden, intimate, human as an untroubled heartbeat, gathering all behind them, bringing order to chaos. And then there is singing. Such singing. “Oh yeah, when the world’s turned inside out.”

It’s not hard to think of these songs as devotional, especially with titles like ‘Eden’ and ‘I Believe In You’ and especially especially after nearly two decades of journalistic reverence. Hollis, like God, remains stubbornly silent about his creation. But perhaps that’s as it should be considering how much silence, how much absence, informs this record. Its emptiness describes these songs as much as the noise does. There are dynamics at play here: single, sustained piano notes echoing into silence or lurching violently into distortion, before retreating again, leaving murmuring ghosts and footsteps. A church organ’s pedals are depressed, vibrating through the gloom.

‘The Rainbow’ bleeds into track two ‘Eden’ at about the ten minute mark, though there little to describe the difference between the two pieces, the palette of instrumentation remains much the same, the loping drums a constant (though the line “Summer bled of Eden” might be considered something of a giveaway). Then, suddenly, we are rising to a climax beaten out on detuned guitar and swelling Hammond organ and Hollis’ passionate exhortation that “Everybody needs some one to live by”, a goose-bump raising sentiment that could have stirred Lazarus had Jesus been off sick that day. It all falls away again, hissing like shingle on the beach, only to return and rise up as persistent as the sea, as untiring as the sea.

‘Desire’ is built around two plucked guitar notes and another spiritualist essay from Hollis, here doing his best impression of Steve Winwood’s “Spanish Dancer”, an obvious antecedent. But that song’s blue-eyed computer soul politeness is left devastated by the tsunami of noise witnessed on the chorus. Hollis would, I’m certain, be horrified to think that he had anything in common with the Pixies, but there’s no denying the “quiet verse/loud chorus” as Hollis bellows, like a hung over choirboy, “That ain’t me babe(!)”. The ensuing percussion and distortion breakdown is ferocious as it pushes finally into one last gasp of a chorus before ending, as it must, with a whisper.

‘Inheritance’ is notable for some beautifully fluid bass and treated organ that twitters off into the ether like Wattoo Wattoo. The wood-wind is like Vernon Elliott’s incidental music to ‘Pogle’s Wood’ or ‘Ivor the Engine’. There’s always been a venerable, children’s television element to the music of Talk Talk, though I will admit it takes a tedious aging hipster like me to point it out.

‘I Believe In You’ was the single. It is not single material. It performs none of the functions of a single, as was (I’m not sure singles serve any function any more). It isn’t catchy in any real sense, although after a few years of listening to it you will come to crave individual sounds, following them with a compulsive linearity; you will want the next noise with a physical greed. But it is not, it has to be said, an ear-worm. It is not the sort of thing you could pair with an eye-catching video, as they had down previously to remarkable effect with Tim Pope’s ‘Life’s What You Make It’. And, while it makes sense as an individual piece of music it makes infinitely more sense in situ. This album is of a piece, relying on call-backs and foreshadowing, it echoes through itself. But ‘I Believe In You’ was the single. And it is the most beautiful and satisfying piece of music here.

It taps into existence. The “chorus” (a redundant term here) is ethereal, a sensation of music, the memory of it. Everything is in flux or flight, there is no substance, the song seems written in smoke, and there is just that spinal column of percussion to cling to. Only that heartbeat drum convinces us that the patient hasn’t been lost, that they are drifting back from the white light. It grounds us when our every instinct is to float away, to disappear like steam off a mirror. As a celestial choir intercedes and Hollis continues his refrain of “spirit” the drumming ceases. It doesn’t start again.

‘Wealth’ is spectral, a drifting away. Hollis imploring somebody to “take his freedom” as the rest of the instrumentation fades away leaving him with his ghostly Hammond, the last words are a choked whisper “take my freedom for giving me a sacred love”. The music drifts off reverentially into silence and it’s hard not to imagine the coffin trundling on its rollers and nudging the furnace doors. I know what I’m having played at my funeral. There won’t be a dry eye in the house no matter how big a bastard I’ve been.

Mark Hollis puts his book down. He rubs the pinched bridge of his nose, red where his glasses have rested. He glances at the piano in the corner of the room. It squats, expectant as Grey Friars Bobby. Then, knees cracking, he rises from his armchair and goes into the kitchen, turning off the living room light. Let there be darkness. John Higgins