In a way, the sheer ordinariness of it all seems like a crime. The death of a person is always a difficult thing, but the death of an artist can sometimes imbue a life with near mythic qualities. So when HR Giger fell down the stairs in his home in Zurich and subsequently died from his injuries, it feels as though the man was cheated of the gruesome, yet appropriate demise many of his admirers may have imagined he’d have preferred.

Giger was always a strange fit for our world. A fine artist who scored his greatest success with a sci-fi movie monster, his art feels consistently devalued, as if it is regarded as the niche interest of obsessive movie fans, hungry to consume more product. He operated in an area that was all his own, using his airbrush to bring the grotesques from his nightmares into reality, and as such, he doesn’t fit in easily to any accepted view of 20th century art history.

But when he contributed design work to Ridley Scott’s 1979 film Alien, he tapped into some primal fear, and his work will long outlive him, or any of us. Perhaps it’s not the legacy he would have wanted, but as far as these things go, it’s certainly very impressive.

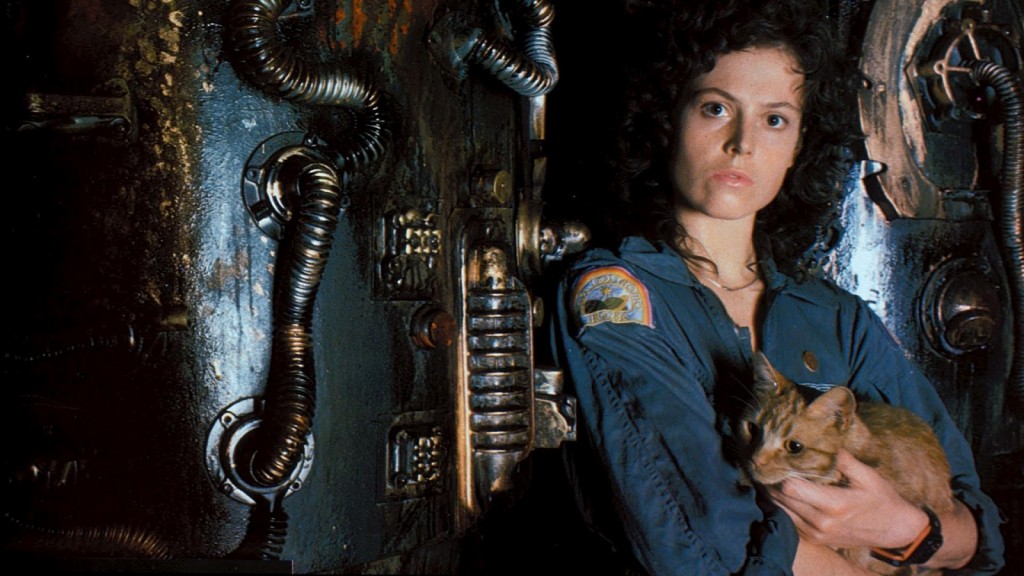

Alien is one of those artworks that is so easy to misinterpret. A blockbuster movie that spawned a successful franchise that has weathered peaks and troughs of critical acclaim, it often seems difficult to separate this opening chapter from all that followed it. But when taken on its own, the movie stands as a real landmark, a visionary work of cinematic perfection that both set new standards in what was possible, and redefined the notion of the impossible. Nothing had been like this before, and nothing would ever be the same again.

Central to this was Giger’s monster, a truly nightmarish vision fusing the organic and the technological. Based on a 1976 painting entitled Necronom IV, the xenomorph was a chillingly unique creation, from the early stages of its life-cycle in a pulsating egg, to its final manifestation as a sleek, deadly, killing machine. Audiences were stunned by the beast, unaccustomed to such beautiful terror, and understandably it took on a life outside of the film itself. But a huge part of the creature, and the film’s impact must come from the accompanying soundtrack by Jerry Goldsmith, a veteran composer with one of the most impressive resumes in Hollywood. Without the soundtrack, the creature is chilling. With it, legendary.

In keeping with a film whose key theme is painful birth, the score had a tortured genesis, one which continues to prove problematic to this day. Goldsmith was a master at creating a fusion of thematic and emotional resonance, unafraid to venture to the extreme end of tonality to make his impact. His score for Planet of the Apes is a marvellously successful synthesis of avant-garde noise and more traditional orchestration, adding a crucial layer to the dystopian setting of the film. For Alien, Goldsmith elected to avoid the obvious, creating a lush, romantic score which would endeavour to capture some of the majesty of space (in contrast to the grungy “space truckers” who populate the film), before delicately becoming enveloped by a sense of fear and horror. Rather than supplying obvious thrills, Goldsmith was prepared to match the nuanced pacing of the film, and let it overcome the audience.

Upon submitting his score, director Ridley Scott disagreed. Wanting the music to have a different impact, Goldsmith was ordered to re-write the score, instead supplying exactly the kind of ‘obvious’ opening he’d wanted to avoid. Despite his consternations, the director loved the re-worked music, and that’s what made the film.

But that’s not the only thing that made the film.

When Goldsmith saw the finished print, he was horrified to discover that editor Terry Rawlings had replaced parts of his original score with work from an earlier film, Freud (1962). Utilising an ominous descending motif Goldsmith had composed for the earlier film, some of Alien’skey scenes were now soundtracked with this piece of music which Goldsmith felt was wholly unsuited to the feel of Alien.

But perhaps the biggest shock came when, in the films climactic scenes, Goldsmith’s work was completely abandoned in favour of the American Romantic composer Howard Hanson, sections of his 1930 symphony ‘Romantic No2’ bringing the film to a close. Ironically, whilst Goldsmith’s original score had attempted to establish a sense of romantic lyricism, it had been replaced by one of the all-time-great Romantic compositions. Goldsmith, predictably, was unimpressed, and decried the compromised score as a failure.

However, when one watches the film with this bastardised version of Goldsmith’s work, it’s almost impossible not to be struck by the perfection of the music used in the film. Goldsmith’s Freud score is deployed to masterful effect, the creature’s acidic blood eating through the decks of the ship, whilst the music spirals further and further into a tense menace. The opening shots of the planet central to the story are rendered unforgettable, thanks to Goldsmith’s re-written opening, full of howling noise, disorientating atonality, and creeping melodic motifs.

And then there’s the ending. As the final battle between humanity and alien plays out, Hanson’s symphony emerges from the darkness, creating a palpable relief to the tension, his melancholic, yet uplifting melody reminding us of just what we’ve lost, as well as the beauty of the deadly ballet that has played out before us. As the credits role, Hanson’s music swells into an almost unbearable crescendo, cementing the movie’s position as a Great Work of Art.

The soundtrack – in any form – isn’t exactly easy to get a hold of, these days, and as such, it’s remained inextricably linked to the film it was such an integral part of. With Giger’s passing compelling so many of us to revisit his work, it’s easy to be stuck by the resonances of Goldsmith’s score, in whatever version you can find it, and Giger’s imagination. Hellish, beautiful, threatening, organic, important; it’s all here. If the alien was the perfect symbiotic creature, then surely the music of Jerry Goldsmith and the art of HR Giger form a suitably impressive partnership themselves. Both men are gone now, but like the beast they are both responsible for creating, their work will prove very hard to kill. Steven Rainey