In April of 1994, Kurt Cobain died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. He left behind a wife, an infant daughter and a legacy as one of the last true rock gods. In the intervening 21 years, a messianic persona has been grafted onto this young man from Aberdeen, Washington. His face is plastered on t-shirts and posters the world over to the point where he has become an apolitical Che Guevara for angry misunderstood adolescents to identify with. There is a plethora of retrospective articles, unauthorized biographies and crackpot theories relating to the man, his music and his death that has created this kind of hero with a thousand faces; a deeply troubled genius carrying the weight of a generation’s disappointment on his shoulders in one interpretation or a drugged up semi-talented punk with paternal issues in another. When all these little cultural artifacts are amalgamated, his humanity is removed in exchange for iconography. He becomes Cobain of Nirvana, Gen-X’s personal Jesus who opted for the needle prick over a Judas kiss and a shotgun over the nails. He is an idol that most feel should be worshiped, but documentarian Brett Morgan seems to reject this idea and with his latest documentary, Cobain: Montage of Heck, he seems intent on performing a reverse transubstantiation.

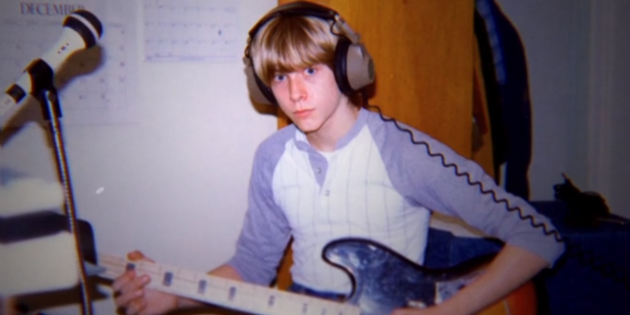

The documentary is, at its core, about Kurt Cobain. It touches on Nirvana, but that side of the story is mostly lip service. Besides, that story has been told time and time again. What Morgan is really interested in is the part of Cobain’s life that is often only touched upon: his childhood. It’s common knowledge that Cobain’s parent’s divorce shaped his life and music indelibly, but Morgan delves much deeper into this territory and is rewarded for it. Featuring talking head interviews with the key family members as well as a huge amount of Super 8 footage from his youth, the film presents the boy that would become the man. The home movie footage in particular imbues the film with this deeper sense of tragedy; watching a 6 year old boy in an Adam West Batman gear ride around in the throes of youth only makes his eventual journey all the more distressing. During the talking head interviews we’re presented with much of Cobain’s flaws: his sensitivity to criticism, abandonment issues and crippling fear of humiliation of any kind. It is in these moments that the film really comes alive and begins humanizing the man. As the film progresses, it hits the major beats in his life: his first hits of heroin, the release of Nevermind and his marriage to Courtney Love, whose interviews are as enlightening as they are terrifying.

Morgan uses his frenzied editing to offer an insight into what many close to Cobain believed his mind to be like. He punctuates these sequences with clippings from Cobain’s publically available personal diaries as well as animated sequences created from Cobain’s own drawings. These drawings are arguably some of the funniest and most disturbing sequences of the film. In using the diary exerts, the film paints Cobain’s mental decline as a much more insidious process. This man was troubled for a very long time and, while the heroin didn’t help matters, the outcome would have always been the same. This presentation of his mental illness and his mental state at the time of his death is expanded on in the home movie footage shot by Cobain and Love. Most of it shot during their six month drug binge and it makes for a thoroughly uncomfortable watch. After a point, you begin to notice Cobain’s weight dropping significantly and his skin quality declining. It’s here that the fact that you’re watching a man slowly disintegrate creeps upon you. Even after the duo have a baby, their habits don’t change and in one genuinely heartbreaking sequence the strung out Cobain struggles to retain consciousness while holding his newborn during his first haircut.

With all this said, the film also reveals another side of Cobain that doesn’t get discussed: his humour. The man was a cheeky bugger and a very funny one at that. In spite of the fact that he is nearly catatonically stoned, Kurt kicks out killer gag after killer gag without missing a beat. When presented with the images of unrelenting misery typically associated with the man, you’d wonder why anyone would spend time with such an unbearable sadsack. But in these moments, you see the person his friends knew. He was the guy who made jokes about Guns ‘n’ Roses, quoted Wayne’s World, came up with and acted out characters with silly voices and names and was wheeled out onstage at Reading in a wheelchair as a joke about his mental decline. He was a person who you’d actually want to spend 8 months in a cramped tour van with. With this side of the man, the documentary has already surpassed about 90% of it’s contemporaries with more portentous presentations.

Where the film really falls down is in its ending. It opts to conclude with Kurt’s suicide attempt in Rome rather than with his successful act a month later. It can be assumed that this was a deliberate choice in order to avoid focusing on the same contentious issue that documentaries like Kurt and Courtney have dealt with before. Additionally, that story has been told time and time again, there is nothing new to be gleaned from telling it again. While the film does choose to end on an absolutely beautiful final musical performance, it’s refusal to offer anything more than a simple text scrawl describing the man’s death, feels at best like a bum note and at worst, like a complete anti-climax. Fundamentally though, the film is very good and is a veritable treasure trove for Nirvana completists and casuals alike. Centrally, the film follows Arnie’s advice from Predator and attempts to make this God bleed so we can see the human underneath, and in this regard it is very successful. This is a film is about Kurt Cobain and every bit of baggage that comes with him, but chiefly it is about the man and not the myth. Will Murphy

Cobain: Montage of Heck runs from April 10-April 15 at Belfast’s Queen’s Film Theatre.