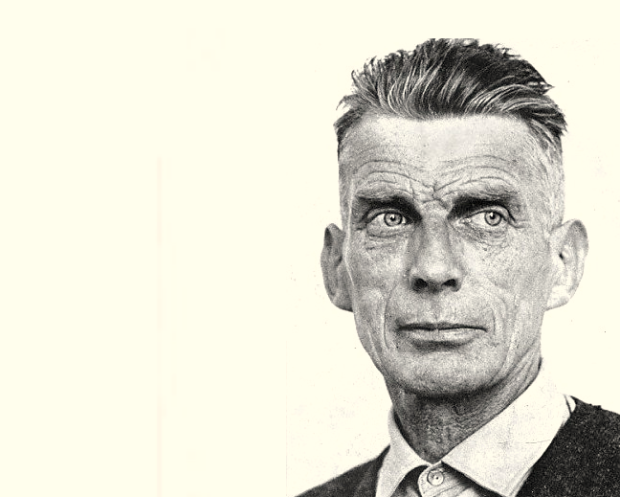

How do you stage Samuel Beckett’s radio play All That Fall in a festival setting when Beckett was, for the most part, dead against theatrical interpretations of it?

Though there had been stage translations authorized by Beckett, notably by Deryk Mendel in Berlin in 1966 and by Christopher Hampton in Calgary in 1967, the writer seemed to regret such translations and would later say no both to Ingmar Bergman and Laurence Olivier’s requests.

When Director Max Stafford-Clark – former Director of the Royal Court Theatre, London – approached the Beckett estate about realizing All That Fall he was asked what his vision for the radio play was. “My vision is that there is no vision”, he answered. Hence the radio play in St. Michael’s School is recited live before a blindfolded audience, thus preserving the essence of the original medium.

The hall of St. Michael’s School features a triangle of seats in the middle of the room and seating around the edges. A dozen or more speakers sit angled upwards on the floor or hang from the walls, encircling the audience.

The cast of this joint production between the Happy Days Enniskillen International Beckett Festival and the London-based Out of Joint theatre company briefly present themselves before masks are dawned and the performance begins.

The sound of birds, sheep, cocks crowing and a lowing cow set the scene but the faintly psychedelic echoes that resonate in the hall suggests an unreality in contrast to the earthy characters and seemingly straightforward linear tale.

All That Fall, unlike most of Beckett’s location-neutral oeuvre, is set in a specifically Irish setting of bygone days. The bucolic soundtrack and rustic characters with their colorful colloquialisms and bawdy humor conjure small-town Ireland in the early twentieth century.

Mrs. Rooney – brilliantly portrayed by Rosaleen Lineham – a moaning septuagenarian, is trudging painfully down the road to meet her blind husband off the train to surprise him on his birthday. She first meets Christy (Sean Duggan), the dung seller, with his cart and hinny. After some chit-chat punctuated by hinny flatulence Christy whips the animal on the rump to gee it up:

“Well, if someone were to do that for me I should not dally,” intones Mrs. Rooney coyly.

It’s about as close as Beckett gets to an Irish take on Last of the Summer Wine, though the series of meetings on the road between Mrs. Rooney and various characters weave darker threads that gather like storm clouds through the narrative.

Mrs Rooney’s humming along to Franz Schubert’s Death and the Maiden coming from a nearby house, is another portent of unease. Her soft cries of “Minnie, my little Minnie” refer to her daughter, who seems to have died as a child.

Still, the often jaunty language is peppered with sexual innuendo, no more so than in Mrs. Rooney’s encounter with Mr. Slocum (Ciaran McIntyre) in his limousine. The fat Mrs. Rooney has to be pushed into the vehicle, while her exit is veritably birth-like. This carry on, truth be told, is a bit Carry On. In between, Mr. Slocum runs over a hen, and Mrs. Rooney seems both to pity and envy the suddenness of its demise.

Mrs. Rooney meets her husband Dan Rooney (Garrett Keogh) off the delayed train and on the walk home asks him about the delay. His determined efforts to avoid answering hint at something untoward. When some children taunt them on the way Mr. Rooney asks his wife: “Did you ever wish to kill a child?”

At home, as the wind and rain pick up, Jerry, a boy from the train station, arrives with something Mr. Rooney had dropped. It is a ball. At first, he denies ownership then angrily declares “It’s a thing I carry about with me.”

Mrs. Rooney asks Jerry what had held up the train but Mr. Rooney tries to stop her questioning. “Leave the boy alone. He knows nothing,” he barks.

Mrs Rooney presses the boy, who states: “It was a little child fell out of the carriage, mam; onto the line, mam; under the wheels, mam.”

The roar of a train and of a ball bouncing back and forth off floor and wall are the final sounds.

Did Mr. Rooney, in a fit of anger, push the child from the train? The audience can only speculate, after all, Beckett himself didn’t have the answer. In Jim Knowlson’s biography Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett (Bloomsbury, 1996) Beckett is quoted thus: “I know creatures are supposed to have no secrets for their authors, but I’m afraid mine for me have little else.”

All That Fall – a kind of whodunit played backward and without real resolution – is as much a play about sounds as it is about words. The musical rhythms of Beckett’s language, the Irish humor and – universal – suffering are brilliantly conveyed by this cast, who move through the audience in a visceral, surround-sound experience designed by Dyfan Jones.

The Out of Joint/Enniskillen Beckett Festival production of All That Fall surely ranks as one of the most original and entertaining diversions from Beckett’s intended genre. Ian Patterson