Like John Goodman’s black ops adventurer whose mania for fantastic beasts and where to find them drives the film, Warner Bros are chasing something big with Kong: Skull Island. Coming with an Avengers Initiative-style post-credit coda and forming a “Monsterverse” (sigh) with Gareth Edwards’ 2014 Godzilla, this new Kong rendition is a reach for a big, stonking franchise to compete with other studios’ similar endeavours.

Peter Jackson’s 2005 King Kong leant into the tragic, emotionally grand tradition of old-timey, New York skyline iconography. Whatever you make of Jackson’s film – and reception was mixed – an eager artistic vision shone through. Skull Island has a less encouraging creative pedrigree: directing is Jordan Vogt-Roberts, whose only previous feature is 2013 adolesecent comedy-drama The Kings of Summer, with story credit to Real Steel‘s John Gatis and a screenplay from the writers of Jurassic World and Edwards’ Godzilla, whose narrative struggled to match the majestic of its terrorizing mega-lizard (improbably, Nightcrawler‘s Dan Gilroy also contributes). This is a producer’s project through and through, and it shows.

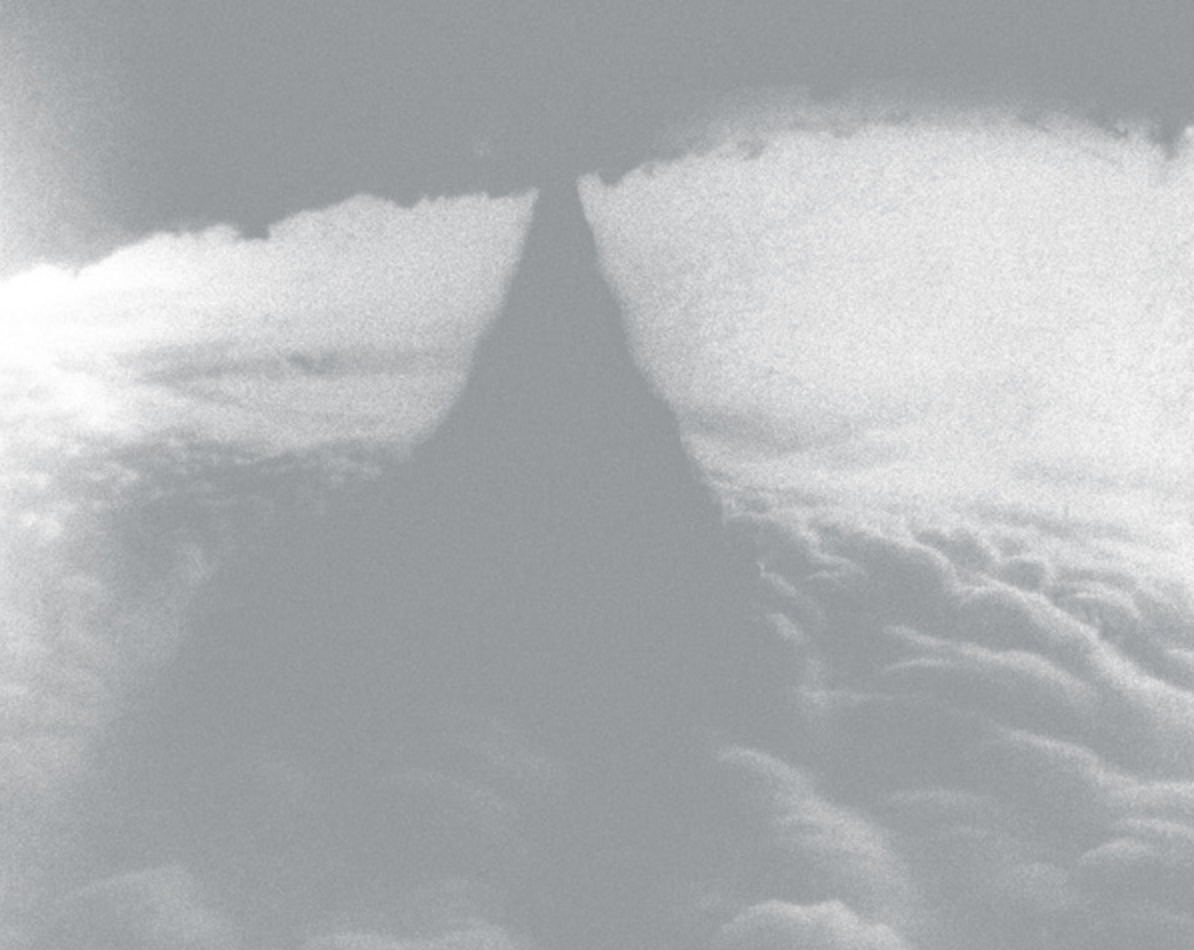

Credit to the film: it doesn’t just recycle the familiar Kong beats. Trouble is, it just recycles just about everything else! Skull Island is a pulpy monster island adventure mixed with post-Vietnam war-is-hell cynicism. It’s 1973 and the President is on television announcing the cessation of conflict in the Vietnam jungle. Bill Randa (Goodman), who runs secret government operation named MONARCH, dedicated to the weird and wonderful monsters of the world, heads to an untouched, remote island in the South Pacific. They are joined by guide and ex-SAS Captain James Conrad (Tom Hiddleston in full Adventure Man mode), photographer and pacifist Mason Weaver (Brie Larson) and a bunch of American squaddies led by Samuel L. Jackson’s Lieutenant Colonel. When Kong doesn’t take kindly to their intrusion, the survivors must deal with an island full of deadly critters, conflicting agendas and the matter of Kong himself.

The cribbings from other movies are obvious. Jacksons reprises his “hold onto your butts!” line from Jurassic Park and the napalm-drenched imagery of Apocalypse Now, Platoon and other sweaty, humid war films is evident, accompanied by unresolved anxieties over America’s military catastrophe. For Jackson’s Lieutenant Colonel, powered by vengeance for his fallen men, the scalp of the great ape promises a kind of redemptive victory. Bending monster island tropes through this lens is a smart spin, but it’s hard to take seriously when expressed in the most generic of terms. Almost none of the dialogue feels natural, and the characters don’t move much beyond adventure archtype status, so back-and-forths over matters of war and peace are hard to take seriously. When the film frames a bloodthirsty Jackson in the same tablaux as Kong, it’s a little on the nose (guys, maybe man is the monster). It’s also a little strange that the ape analogy is applied to the cast’s single black member, though that has more to do with Jackson’s cornering of the “tough motherf-er” casting market.

Skull Island‘s central problem is that like the titular beast, it’s big and woolly and never light on its feet. There are some nicely staged sequences, but too many slow-mo helicopter shots, too many montages to period rock songs and too much time spent on bland soldier types who are going to end up monster meat anyway. Thank God, then, for John C. Reilly as a grizzled, katana-slicing castaway, who has been marooned on the island since WW2, injecting some much-needed flippancy. In comparison, even Kong himself feels small and low on personality, an incidental presence in his own film. Conor Smyth