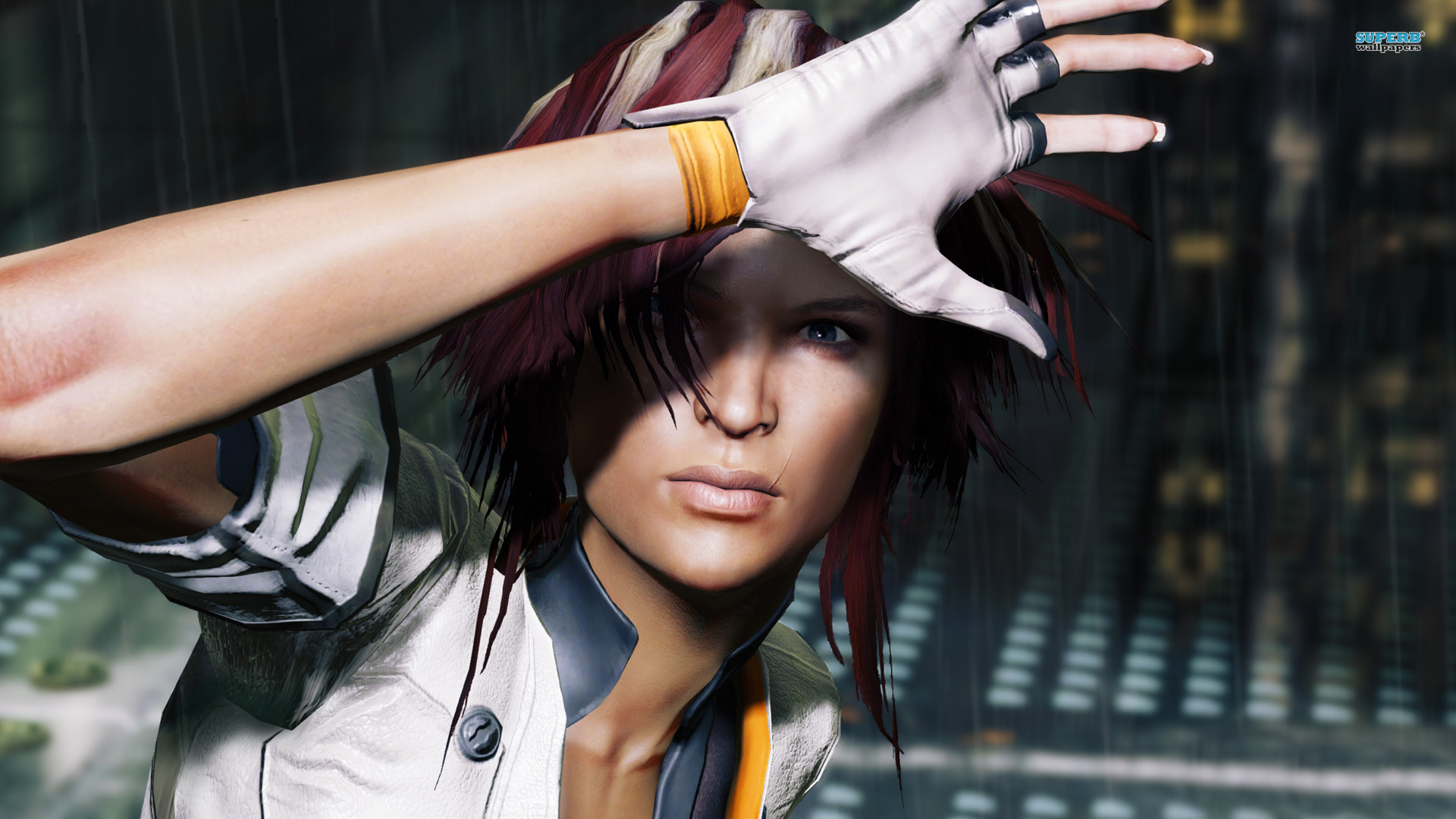

Put simply, God Of War is not only one of the best games on the current generation of consoles… it is also one of the best games ever released for any console. Yes, this may sound like embellishment, a factually questionable statement similar to those made by overexcited teenage boys just out of their first live concert: “Dude, that was the greatest thing ever, I mean, like forever!” But it’s true: God Of War is out and out excellent, so much so that at times it can be overwhelming. There are so many things happening at once onscreen, so many skill trees to complete and master, so much dialogue to soak up, so many branching quests and hidden areas to discover… unlike other flagship titles, it is both a mile wide and a mile deep. It is does not take long for the player to realise why God Of War took the development team five years to put together. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Knowing that the final verdict is that the game is great is helpful but let’s take some time to look at exactly why it is quite so great.

Firstly, and chiefly, the magic ingredient is storytelling. We have said it before and we will no doubt say it again: the best videogames tell engaging, involving and rewarding stories. Yes, there is a time and place for shooting zombies in the decaying kisser or for rescuing a princess from a giant, maniacal turtle but the games that truly resonate, the ones that stick with you for days afterwards, are the ones that invite the player on an emotional journey. Such releases are few and far between but when they arrive, they tend to do so with a wallop. God Of War is very much a character study – it is the eighth instalment in the franchise, despite what the singular title might suggest – not only of Kratos, the mythological giant killer and Titan slayer now living a secluded existence in a forest cabin, but also of his young son, Atreus, who longs to be as adept as merciless brutality as his father. This odd bedfellows are thrown together in the aftermath of the death of the mother, a trauma that occurs before the main narrative but that has significant repercussions for the direction and tone of what happens thereafter. As has already been well documented, its touchstone is The Last Of Us, in which a surrogate parent / child relationship is juxtaposed alongside a world that is sickening in its viciousness. Kratos’ attitude to Atreus – at first irascible, later more affectionate and respectful – and their interaction provides the beating, pained heart of the story. Atreus’ constant chatting not only is the perfect foil to Kratos’ taciturnity but also supplies a lot of the game’s rich lore – the stories in part pilfered from various sources of Greek and Norse mythology and which flesh out a game world that is epic in all senses of the word. The combination of Atreus recounting tales passed on by his late mother with the details of environmental storytelling – fallen statues, abandoned castles, rotting waterwheels – is a masterclass in world-building. Further, it adds an element of mystery that is key to the plot and which will not be divulged here: why Kratos, the immortal Spartan warrior, has abandoned his mission to destroy all of the deities that ruined his life, and why the purgatory in which he now hides is decaying and falling apart.

These elements are a marked departure from previous God Of War games, which prioritised button-mashing and quick time events at the detriment of everything else. This episode dares to be different: the pace is much slower and the conversations longer, with more emphasis placed on exploration. Another key comparison is the recent Tomb Raider reboot, which was built around the “Metroidvania” template of withholding certain areas until the player has gained certain skills. God Of War takes this mechanic to an exciting new level: the map, a convoluted and at times confusing expanse of furcated routes, conceals dungeons, caverns and valleys that can be missed entirely if the player does not take the time to explore every nook and cranny. A long section of God Of War takes place on a huge lake, around which are dotted multiple jetties leading to side quests and “favours”, missions that are optional but upon completion will bring rewards such as new weapons, armour, magical powers and so on. The map is visually breathtaking (a witch’s sylvan lair and a sequence set inside a kind of beehive brimming with evil elves are particularly memorable) yet it also offers the incentive to go further, to delve deeper, to search for secret entrances.

When the fighting starts, as it surely will do, the action is absolutely brutal. Kratos did not earn the nickname “God Of War” by being skilled at decoupage. While he is good at duffing up baddies with his fists, his weapon of choice is his “Leviathan Axe”, which he uses to pummel, slice and cleave with wild abandon. Like Thor’s hammer Mjölnir, this blade can be chucked at enemies and then recalled with the twitch of his fingers (or a push of a controller button), and this action never grows tired. The solid thunk of the handle slamming into Kratos’ palm is always pleasing. Combat is a complex juggling act of throwing, hitting, parrying, magic casting and instructing Atreus to fire stun arrows at an increasingly inventive phalanx of enemies that grow outward and upward in size – an RPG staple is having assistants to help out in battle. Some of the beasts you meet, particularly the irritatingly mobile witches or enormous trolls who spew beams of lava out of their chest, are tricky to beat but the sensation of vindication once you have done so is deeply satisfying, more so when it is accompanied by a bone-crunching animation of Kratos pounding them into the ground or ripping them in half with his bare hands.

One of the reasons that the player feels fully involved in the action is thanks to a clever game camera that never cuts or pans away, like an even more aesthetically elaborate version of Birdman or that opening shot from Goodfellas. The lens is always trained on Kratos, giving the gameplay a real sense of intimacy and complicity with his quest to take his wife’s ashes, as per her last wish, to the highest point in the kingdom. The camera sticks close to Kratos even in the thick of a frenetic battle, which is impressive if you take the time to stop and think about exactly how the developers pulled it off. However, there is also the issue of what it is at stake: both Kratos and Atreus are hugely sympathetic creations, which increases the sense of peril exponentially, even when the game tips into potentially silly territory such as engaging in conversation with a severed head whose memory is not quite what it used to be.

There are plenty more superlatives that we could lavish upon God Of War but to say too much would spoil the many surprises unveiled during Kratos’ big day out with Junior. The game is a marvel on so many levels, not least of which the way in which all of its moving parts interlock and work together. Like the best pieces of art – and again we should reiterate that the video game medium is by nature artistic – it has fluidity and flair that feel at once entirely natural and genuinely surprising. Ross Thompson