Outlining an ethics of documentary making in The Image You Missed, the late, acclaimed film-maker Arthur MacCaig (via Ernest Larsen’s crisp, twangy voiceover) describes the subject of the lens’ gaze as one who is forced to ‘account for themselves’ — their choices and responsibilities and lived experience. Who are you? And why are you doing what you’re doing?

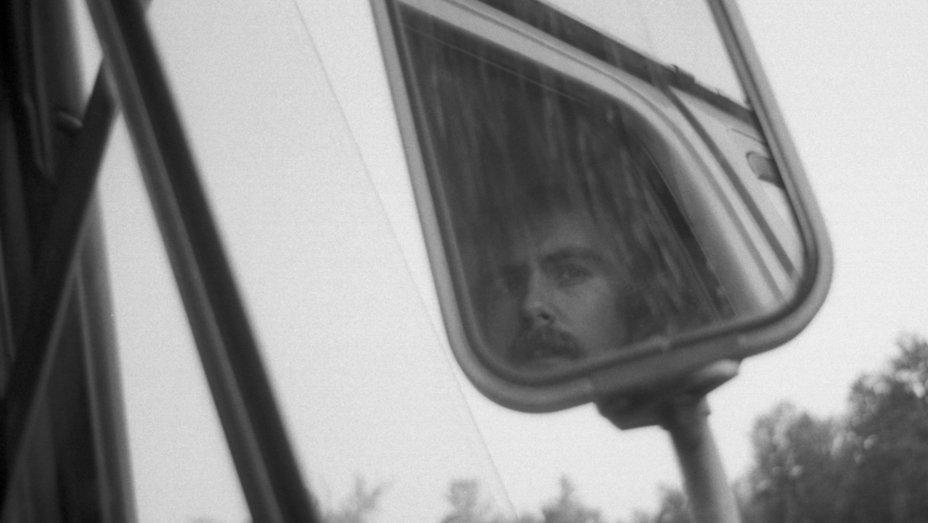

McCauley’s son Donal Foreman, Image’s director and editor, uses his own film to turn the camera’s scrutiny back on his absent father, producing an engaging, clever consideration and critique of MacCaig’s legacy, of political docs more generally, and of the subtle differences between looking at and looking for.

MacCaig, an Irish-American whose ancestors fled Ireland during the Famine, visited Belfast as a tourist in the late ’60s, just as the city was sliding into the Troubles, and fell for the place. Eventually he lived and worked in Paris, but visited Belfast periodically to make visceral, difficult films about the Catholic community and their struggle against the forces of the Crown.

For MacCaig, whose political and ethical positions are outlined in narrated transcripts, the film-maker’s role was to provide counter-imagery to the official narratives of the British media, which framed the Northern Irish conflict as one of law and order (terrorism versus the state). Embedded in the working class communities of Belfast and Derry, MacCaig viewed the conflict as one of anti-colonial resistance, a project of class solidarity. After his death in Belfast in 2008, his son Donal went to Paris to clear out the vacant flat, and began sifting through the archive of footage he found there, much of it unseen. The Image is the product of this project of retrieval, acting both as a therapy and a reckoning.

Father and son come with different kinds of personalities, and with them different formal and political perspectives. MacCaig pursued his artistic commitment with iron certainty. Foreman is more sensitive and considered, drawn towards the impressionistic film-making of his uncle, Sean Brennan, who shoots for colours, light and natural beauty.

MacCaig was on a mission to expose the blindspots of orthodox thinking, but he had blindspots of his own. And his son was one of them. Letters from Arthur to Donal’s mother Maeve, flesh out his distance from the family; Arthur is always in Paris, always tied up in something, always too broke to make it to Dublin to see them. When Mom and the 8 year-old Donal finally visit him in France, Arthur absconds from all obligations towards the boy. Absolutism re-contextualised as evasion.

The Image is a study in time, in the absent and the unseen, in the ghosts trapped in photographs and film reels. Images survive but become distorted: the world goes on, and bends around them. Moments of political rebellion enter a chain of replication and commodification: murals, poster graphics and, finally, Instagram backdrops for New Belfast’s cruise ship gawkers. After all this sacrifice and rage and grief, the war and the peace has delivered a city that looks like every other shoppified urban centre of the developed world, far from the socialist, democratic Republic of Donal’s father’s imagination.

Foreman’s film is a lament for the loss of faith in the power of conventional politics, and in the power of conventional images too. Foreman attends Occupy Wall Street, and there is some subtextual connection between Zuccotti Park and the class resistance his father coveted, but the son is unsure about Occupy, which seems over-photographed, over-stylised at birth.

At a Q&A afterwards, Foreman noted how a culture of ceaseless image-making makes the documentarian’s job both less and more necessary. Here, the philosophies of Foreman and MacCaig, so different, converge: the lens as a tool of accountability, both political and personal. As a Troubles meta-doc, The Image is layered and fragmented, but also fundamentally honest and curious in its search for connection and understanding.

Conor Smyth