Queen’s music is like the air. So if you’re going to give them the biopic treatment, you need to peel back the gloss and the familiarity a little, and give us a peek at the complications, the darkness and the extravagance of an icon like Freddie Mercury. Their tracks have been drilled into the DNA of modern background noise: for Bohemian Rhapsody to feel in any way fresh, it needed risk. It has none.

The product of a difficult gestation, Rhapsody arrives after cycling through leads, screenwriters and directors. Bryan Singer gets the sole director credit, but he was fired mid-production for unprofessionalism, leading to Dexter Fletcher being drafted in to finish up. The early departure of Sasha Baron Cohen, originally cast as Mercury, over creative differences, and the presence of Brian May and Roger Taylor as creative consultants, and former Queen manager Jim Beach (played by Tom Hollander here) as producer, flagged up the strong possibility of a film geared towards legacy preservation over emotionally truthful storytelling.

Bohemian Rhapsody meets these expectations squarely: it’s an outrageously cliched hop, skip and jump through the Greatest Hits, a bland product of committee, lacking the essential spices of danger, camp and innovation that made Mercury, May, Taylor and Deacon interesting in the first place.

1985’s Live Aid concert is the opening coda, and eventually forms the film’s crescendo, closing with that slowed-down, memorial haze walk-off that is music biopic 101 (“Dewey died three minutes after his final performance”). We start with a twenty-something Freddie Bulsara (“Mercury” came later), living with his Farsi family in Middlesex, slinging baggage at Heathrow and haunting local nightspots, stumbling one night upon May and Taylor, student musicians desperate for a new main vocal. One of the film’s few bright spots is its flagging of the exotic otherness of the Zanzibar-born Farrokh, often discounted in the collective memory of Mercury, even if it’s treated with a slightness and awkwardness that characterises the film as a whole.

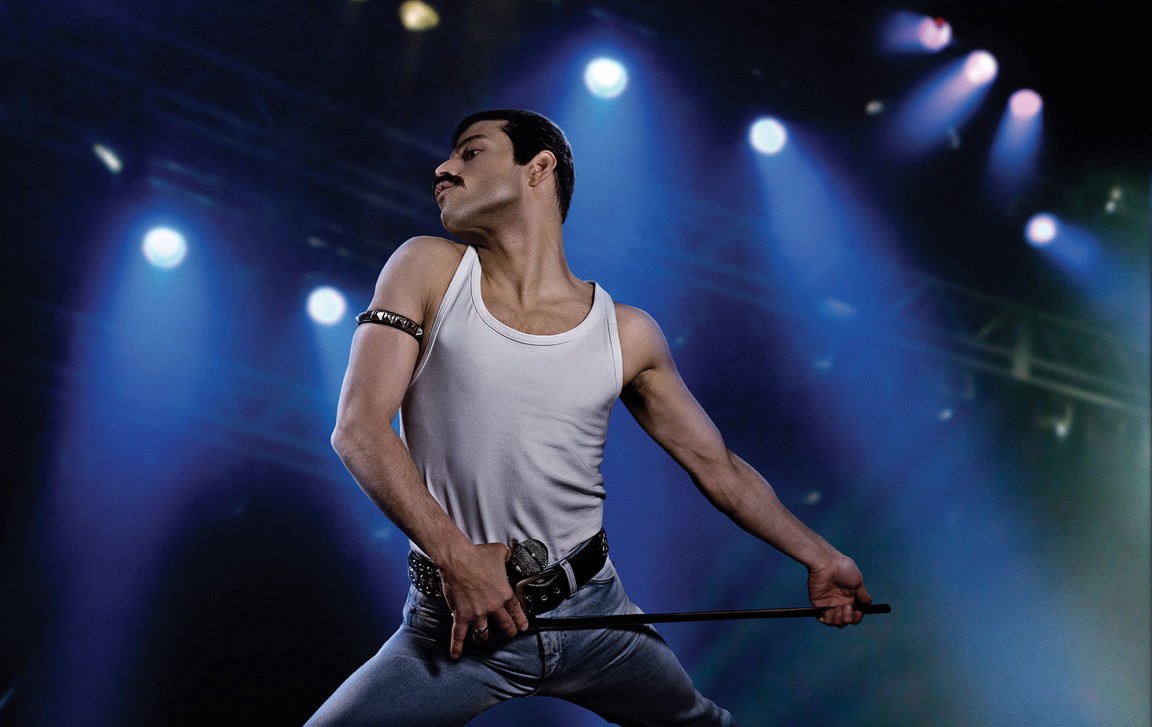

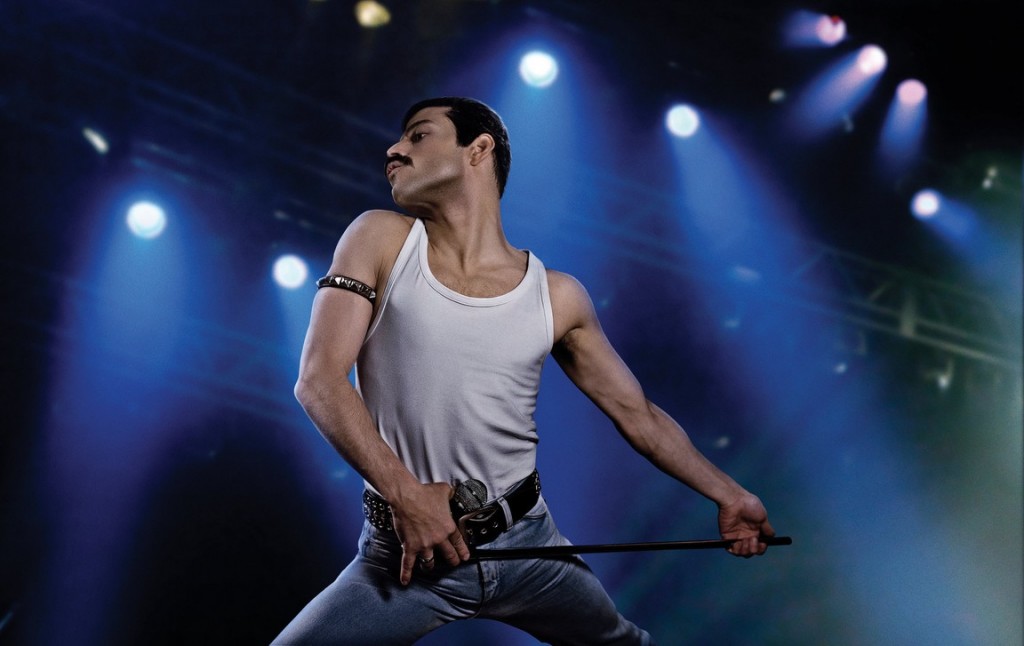

Rami Malek brings taut energy and an alien kind of quality to his Mercury, trying to overcome slightness of frame with a strutting, flouncing stage presence, but even when he nails the moves it never really feels like more than a game of dress-up; through Halloween front teeth he spits catty one-liners in record company meetings and calls everyone “darling”. Much of the time watching Malek’s Mercury is like being at a house party with an art institute extrovert who drinks too much and thinks talking like a drag queen makes him well gas.

The disconnection of Rami’s performance from what’s going on around him is heightened by screenwriter Anthony McCarten’s thin treatment of supporting characters: the rest of the band, Mercury’s girlfriend and great love Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton) and the various hangers-on. The most substantial other personality is Mercury’s infamous personal manager and enabler Paul Prenter (Allen Leech, living up to his name), here a cartoon villain with a Norn Iron accent, the Blofield-style author of all Mercury’s pain.

Without the stomach for uncomfortable, 12A-breaking takes on its central figure, or anything approaching a personality for the band members as whole, who come across as self-satisfied bores next to the mercurial Mercury, Rhapsody passes by with no impact or insight.

Cramming in the whole arc of Mercury’s career, anything interesting or decadent is only half-glimpsed at. So spotted blood on a handkerchief and a conversation at a doctor’s office stand in for the degrading AIDS experience; a wink at a truck stop stands in for aggressive sexual indulgence; a cheesy montage of red-lit dudes in BDSM collars stands in for the underground queer experience. Montages are a problem more generally, the screenplay barrelling through tours and landmarks without any context to place them in.

The dramatic irony is unsubtle and almost embarrassing, like Mike Myers’ mutton-chopped EMI exec screaming that “no-one’s going to know who Queen are”, or a band member doing that hack biopic trope where out of the blue they’ll play an iconic chord or arrangement and everyone turns round like “what is that?”.

Mercury’s rise, fall and rise again is built on a structure of cliches. He finds fame and money buuuut that doesn’t make him happy. So he goes off by himself to make solo records in Munich and ends up overworked and depressed, missing his bandmates. (“You’re burning the candle at both ends” is a line actually said out loud.) At Live Aid he finds redemption: the phone lines are dead until Mercury takes the stage and brings the fire, and suddenly they light up, single-handedly saving Bob Geldof and all those African kids!

Suffocated by shortcuts, Bohemian Rhapsody feels small. And that’s hardly a word that applies to Mercury.

Bohemian Rhapsody is out on wide release.