A northern voice cuts through the chatter; “this train is for the following categories of passenger only—recipients of universal credit or minimum wage, the lonely, the disenfranchised, the disillusioned, the lost, the grieving”. You pull your jacket closer to fend off the chill air that fills the carriage, wiping at the window with your free hand. It’s foggy outside, you make out nothing but a few barren trees and distant hills. With a heave the train begins to move, and before the conductor has even announced the destination you know where you’re going.

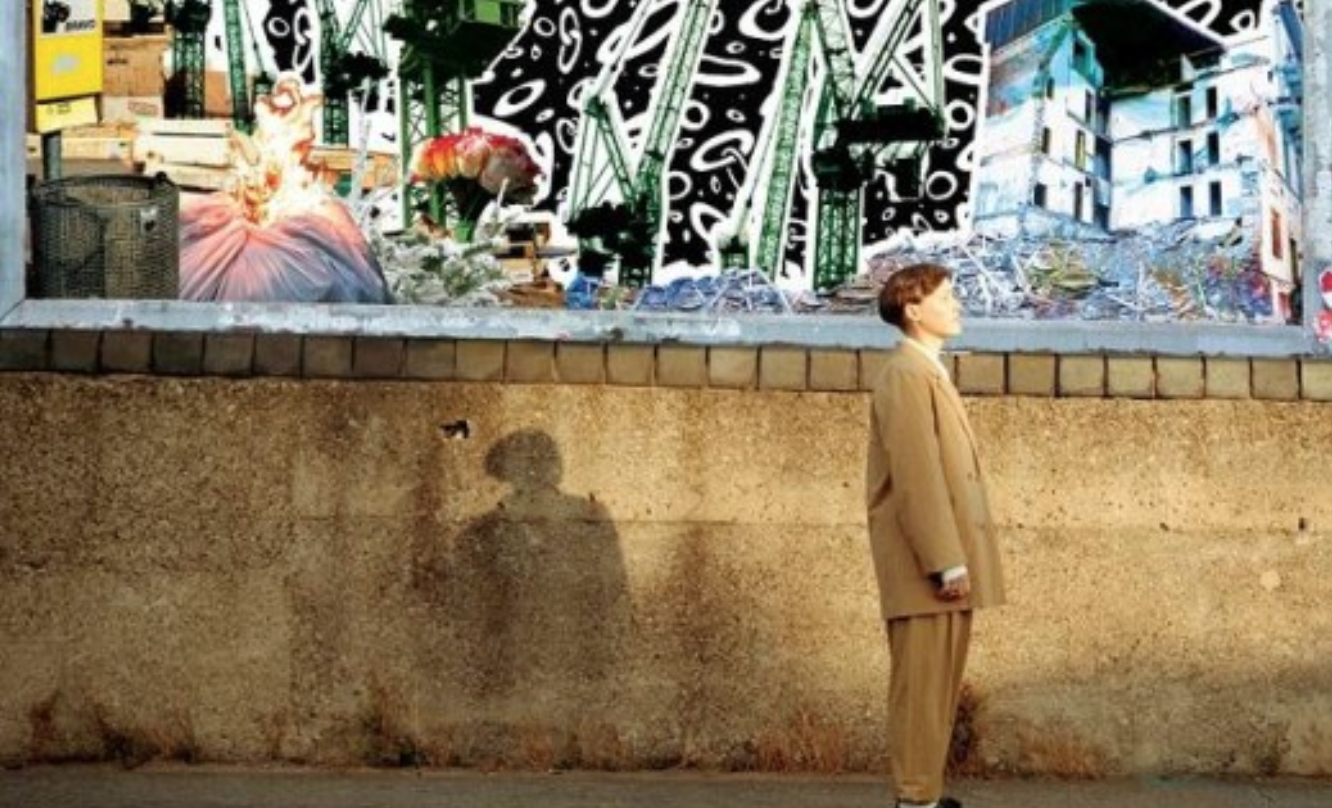

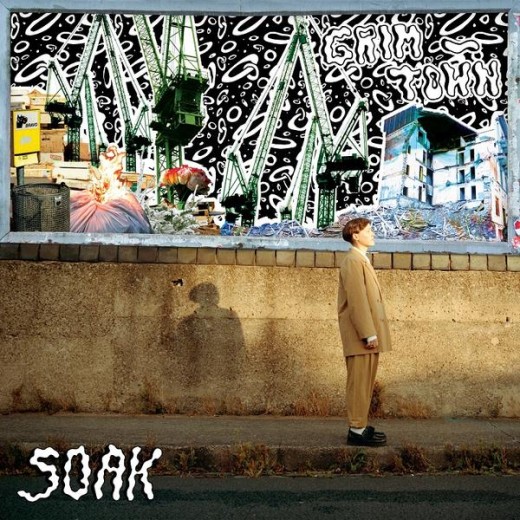

Bridie Monds-Watson’s (aka SOAK) sophomore album Grim Town comes after almost four years since her debut Before We Forgot How To Dream caused quite the stir, winning her the Choice music prize and getting her nominated for the Mercury Prize. Going on tour shortly afterwards, she continued to build a name for herself playing at festivals across the globe. But while accumulating that deserved reputation and adoration, she began to neglect her personal issues and thoughts. These fears and feelings distilled and hardened over the years so that when it came time to write again, she felt as though she didn’t know how. Crippled with pressure from the very success she had earned.

Suddenly the meagre opinions of anonymous listeners transfigured into insurmountable expectations of supporters and admirers, all with names and opinions and crucially, voices. In coping with these thoughts, Grim Town was born, a metaphysical location derived from her hometown of Derry. Peppered with rusted percussion and echoing vocals, it acts as a nostalgia infused residence filled with cathartic explorations as well as contrasting beats of resentment and appreciation for an unbearably monotonous humdrum that somehow became a sign of home.

‘Knock Me Off My Feet’ echoes this sentiment, using sunny guitar strums and lively percussion to pull along the anecdotal lyrics. “I’ve always done the best I can / To get out of my neighbourhood / But you’re still my home” she sings, acknowledging the push and pull of growing up in a small town where the unknown is a scarcity that needs to be rationed.

The streets are empty bar for a few sporadic vehicles, one of whose backseats is occupied with the tears of divorce. “Double Christmas, make up for the year just passed”; a sense of pleading trailing the raspy notes and rhythmic chorus horns. The subtle additional instrumentation here recurs throughout the album demonstrating a wider sense of music control, which is perhaps most noticeable on the breakup ballad ‘Crying Your Eyes Out’. Commencing with a traditional focus on vocals with piano backdrop, the song thrusts itself into a conflicting march of determination and doubt after Monds-Watson asks “Will I ever be enough”.

These experiences of emotional toil however are often met with internal skepticism, begging for justification against the internal betrayal of feeling vulnerable and immature in your ’20s. The phrase “coming of age” has become inherently convoluted and problematic. Insinuations perpetuated by modern culture paint it as a one time event, stretched over a number of formative teenage years with a beginning and an end, commencing the moment you lock eyes with the person you fancy before hastily returning them to your withered copy of The Great Gatsby, and ending once you’ve spent several years figuring out exactly who you think you are while some distant melancholic song plays that somehow acutely reaffirms everything that you’ve been processing. This damaging notion hinders emotional intelligence and growth, and so when you’ve officially become ‘of age’ you can be faced with an experience or an emotion that your gut tells you should have happened already. It holds a knife to your throat and taunts you with ridiculous convictions of experiences being inherently linked to age. Monds-Watson refutes this completely.

While sonically distanced from BWFHTD, Grim Town falls into a formula of comfortable tempo and instrumental landscapes that make some of the tracks feel all too familiar. ‘Scrapyard’ and ‘Maybe’ give way to this, falling back as tracks that don’t immediately discern themselves as particularly noteworthy when placed next to the sentimental ‘Valentine Shmalentine’. It is something we hear throughout the album, and as such it’s difficult to ignore the idea of these tracks replicating the homesick/sick-of-home feelings that she so poignantly portrays.

On Grim Town, Monds-Watson conveys a compressed journey of growth that society insists should have already happened. We are always arriving, and she knows that now. “Nothing looks the same / Now I’ve changed the frame” she closes out, not because we are leaving the grey, but rather because we have absolved ourselves of guilt, allowing our perspectives to become multi-faceted and erudite. And though at times you may revisit the ramshackle antiquities that you forged with unexpected fury and insistent tears, they will dilapidate, crumble, and inevitably fall as sprawling memories of chipped teeth and trembling rage across weed ridden gardens. You will reach for them to rebuild, to experience again that with which you are so familiar, but as your hand meets the cold glass of the moving carriage and the cinder blocks turn into bricks turn into matchboxes, the conductor announces the next stop; Grim Town. Mitchell Goudie