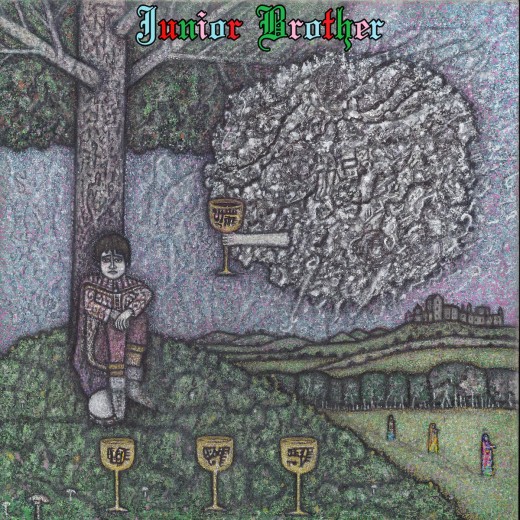

Imagine Joanna Newsom had gorged on grainy VHS tapes of Richie Kavanagh instead of the modernist compositions of Ruth Crawford Seeger, weaving guitar stabs and tambourine whacks to soundtrack drunken treks through rural Ireland. This verdant picture, brought forward by Kerry bard Junior Brother, glistens to life on his enchanting debut album, Pull the Right Rope, released through Galway’s Strange Brew label.

Born and raised just outside of Killarney, the origin story of Junior Brother, the performance name Ronan Kealy nabbed from an early 17th century play he studied in college, is equally as pristine and adventurous as his music. As a bug-eyed nine-year-old boy, he penned his very first song, having taught himself guitar on a “banged-up nylon acoustic”. He once said that, when was 10, he was given “free rein to indulge” in his imagination. At one point, he stayed in a cardboard box in his back garden for a week, decorating and scrawling pictures all over his temporary abode. A full decade and six years later, this playfulness dovetails with his unpriestly writing style and strangle songcraft— a singular voice in a sea of musicians more than happy to rehash folk and singer-songwriter tropes.

Junior Brother’s last full release, the 2016 Fuck Off I Love You EP, bewitched as much as anything on his debut. But with the exception of songs like ‘Witches Willow’ and ‘Hungover at Mass’, his meandering, tempestuous style was still in its infancy, mere sketches of the magic to come. Pull The Right Rope is noticeably three-dimensional, driven by careful, airy layers of birdsong, whistles, string and flutes, with guitar as percussion and as texture. Its arcane roots, with references to wine, nature, and rural life, drags and swirls you around until all that is visible is green and brown and yellow. The songs that appear here, written fitfully over a five year period while he was between the ages of 20 and 25, naturally represent his most epic and musically inquisitive set yet: a church bell opens ‘Girth and Plain’ before disintegrating into guitar lines worthy of a post-punk band. It is, like the best Junior Brother songs, informed with a towering sense of wonder; fantastical 19th century folk in a time where technology pervades every second of every day. “Where sky and water meet / And the trench of its reflection / Locked into a farmer’s stream,” he sings, revealing a warped sense of what’s real and what’s not in the wilderness when you’re in awe to the point of inebriation. Such unforgettably striking and naturalistic detail saturates the album and give it oxygen.

Everything here is lovingly performed; the touch of a true musician’s musician. Junior Brother’s trusty tambourine—an extension of his body—creeps into every crevice. And while his pin-pricked guitar playing on his debut can be mesmeric—sharp and implacable, terse and unbound—it’s his singing that gives his music agency. The noodling, trad-recalling guitars, as sharp as machetes, come together in perfect union with his delightful, period-inappropriate squall of a voice — even if it is an acquired taste, severe and dyspeptic. Throughout the album, his Kerry drawl lilts elastically, autonomously, mirroring the quivering guitars. At times, he emulates the the near-histrionics of Richard Dawson. On the boisterous, rebellious lead single, ‘Full of Wine’, he crows whimsically one moment, his voice rising up and down as fast as throttling heads in a barnstorming trad session, then, shunning the former style just a few lines later, he settles into a smoother Damien Rice vamp. In truth, he vocalises like he’s allergic to rhythm and structure itself, and his lyrics are infinitely too original to reduce to a meaningless label like singer-songwriter.

Tender and at times inscrutable, his lyrical realism and his musical whimsy can be difficult to trace back to a source. Telling is the fact that he didn’t grow up in a musical family like many folk traditionalists. Instead, it was always a very personal thing for him; toying away with a rock band in secondary school and occasionally playing piano in Killarney bars were ultimately unsatisfying, artistically and spiritually. You’d imagine his formative influences sound scarcely similar to his voluminous mode of folk. Melodies slither out of the album like gas from fissures on the earth, like summer weeds in an untouched garden. “Your teeth grind and tremble at the stories of your shame / Once you feel these twisting fingers you will know my name,” he sings on the gnarled chorus of the gripping ‘You Will Know My Name’, with just an acoustic guitar lingering in the air like a fragrance passing over shoulders. Although he sings monosyllabically here for emphasis, the song never runs out of fuel, tumbling into a wall of atonal guitar shortly thereafter. This song, more than others, reads as ruralism-as-song, by turns describing roads, horses and decamping for the west — a wild, rollicking anthem for culchies and dreamers alike.

Across the album, Junior Brother warps the traditional role of an Irish singer-songwriter—soul-baring, observational, breathlessly honest—into music altogether more bewildering. He does away with the damp, anodyne mood music — charged up with either big production or ornate affectations, marketed for either rustic beanie-wearers or alternative-ish radio —popularised by many artists of the folk ilk, preferring something more crushingly intimate: the imagination, what keeps us from going insane.

‘Purple Circle’, a nine-minute prog-folk odyssey, is the most rarefied offering, leaving it clear just how expansive his insular style can get. The opening two minutes of guitar plinks, fulsome and bright, could in another dimension easily be drawing from Neutral Milk Hotel or some other noughties indie sketchbook. This breeziness gives way to something grander, however, with the introduction of a woodwind and what sounds like pipes groaning, a swarm of aural locusts. “It could make a fella leave himself behind / It could make a man pure lose the plot,” he sings cryptically after the intensity of the chorus subsides, just before detuned guitars shred and squeak. He could be referring to the push/pull of the countryside, (trad-like flutes enter the picture later), or he could be alluding to love (he is utterly transfixed); who cares when it sounds this good?

Occasionally, Kealy’s noble portrayal of the uncanny rural is overbearing to the point of cloying, a deluge of picturesque cul-de-sacs, dairy cows, wildflowers, tiny pubs, smoke pipes, ruddy faces, overgrown ditches, woolly jumpers in the summer heat, and people saying grand and surely. Which is not to say that the album fails in any respect — this undiluted Irishness is powerful and refreshing — more that one full listen-through is required to take in the scenery. Spots of tinny production in places detract from, but do not completely overshadow, the guitar playing and general sense of wonderment. Over time, he will decide whether to smoothen the jagged edges or bury himself further in the grooves. The thumps and clunks of hands hitting guitars, the vocal wheezes and gusts of tambourine; they’re all imperfections that clasp themselves to a weird and wonderful tapestry.

Junior Brother’s sound is one unexplainable by streaming trends or even, for the matter, the new folk scene itself. Repeated listens are appropriate, if not totally necessary, to meaningfully grasp this album’s breadth, where his voice crackles with verve and a terrible wit only someone born in Ireland — more specifically in rural parishes— understands and appreciates. And there is a cleverness, a distinct sense of identity not many can point to, in how he works his voice around the green, bushy overgrowth, dodging the bales of hay. As he skulks around the countryside looking for meaning, the least we can do is join with him on the journey. Colin Gannon