In a 2016 interview the composer and saxophonist Matana Roberts asks, “Where is the new language for how we talk about difference?” Sceptical about current protest movements’ uncritical resurrections of previous vocabularies of struggle – which, in their reliance upon dualisms of black and white, us and them, reinforce the structural underpinnings of three decades of culture warring that led, quite logically, to brexit, Trump, Bolsonaro, and other demagogues around the world whose only overtures are ones of blame and resentment – Roberts’ suggestion is that only replicating older articulations of opposition dulls our ability to construct a language fit for present day, intersectional struggle.

Her music, alongside the work of Kendrick Lamar and Moor Mother – in its restless pursuit of new terrains, its mixing of choreography, film, visual and sonic collage, sampling, History, sound theory and sound art – insists that it exists on terms other than those imposed on it. Echoing the writer Édouard Glissant’s assertion, “nous réclamons le driot a l’opacité, it demands to be outside the ordering impulse of transparency and clarification, of capitalist taxonomy, but crucially – generously – it calls to do this via collective, inclusive self-determination. I want to talk about how Matana Roberts’ music incites and invites us to think about what kind of language, what kind of thinking, is capable of addressing the multiple shifting modalities of her compositional work, as well as the broader ways that it implicates itself in a present quilted out of contested histories. I’m interested in getting entangled with it, and I may not come up with any answers, but my approach to writing here is an improvisatory one, and I write this as I listen to the four chapters of her remarkable Coin Coin project.

What guides and propels her work is the gait of a variable foot, a nimbleness that dances across diverse terrains, advocating that things keep up their proper confusions and uncertainties. The discomposure of experience, of living, of the struggle of becoming, not angled towards a need for completeness or poised towards resolution, but instead admitting a shared sense of indebtedness, is what colours her work and seemingly allows it to shape shift each time one gathers oneself amongst it. Her music is one of a particular post-vernacular hybridity that requires of us more than one interpretative process. There is a gravitational pull that draws in much more than can be distilled or reified into a consistent and coherent critique. This might be because, although her work is saturated in text, it explicitly hinges on what Richard Quinn in his book The Creak Of Categories describes as ‘signifying sound as well as indexical language’; that is, the sensitive, sensual performance of text as a way of attending to the structural biases and injustices that underpin how we speak what we choose to speak of. Her vocal puppetry ventriloquizes gospel, prison song, scat, spirituals, old-time country, storytelling, and personal and historical testimony, while her saxophone narrates and brings us into the present day avant-garde (as Matana Roberts, the artist), but is also in a process of transfiguring tradition – bebop, free jazz, dixieland, blues – acting as a spiritual, sonorous guide through collisions of American social, cultural, and political histories. These are rituals of self-actualisation and self-determination, and the layering of music, concrete sounds, and text, act as a way of stirring, conjuring, and complicating histories that are always fighting against creeping essentialism.

This essentialism comes in many forms, and one of them is the algorithmic demand of curated playlist culture that shapes so much of our listening topography. Roberts’ music contains too many fissures to sit seamlessly inside a data driven Spotify playlist called All The Feels or Find Your Empowered or the bleak corporate endpoint suggested by Black Excellence™. Like Moor Mother’s excellent Analogue Fluids of Sonic Black Holes (2019), Roberts’ Memphis runs counter to the sonically flattening technological demands of streaming services where we are increasingly exposed to music written with the aim of getting playlisted by the likes of Spotify; those hallucinatory virtual de(s)pots to which we address our art – and submit our financial security – that increasingly feels less than consensual. These albums’ musical and narrative crosscurrents, the blurring of tracks into each other, the multiplicity of voices, quotation, the whispering of sounds and words amongst themselves, the interruptive splicing of musical styles decades (centuries) apart, the sparring of electronic and instrumental sounds, and the field recordings threading through the albums like a sonic quilt – ‘panoramic sound quilting’ is how Roberts frequently describes her process – sit joyously and jarringly against the content driven, frictionless, curated milieu of the Airbnb-hopping digital nomad passively listening to their mood enhancing, productivity optimising playlists. The inherent refusal of the fleeting, the passive, of ambient mood shaping in their music isn’t a slipperiness and this slipperiness isn’t a slyness, or cynicism, and although it is tempting to frame it within the modality of the Afro-Caribbean diasporic legacy of tricksterism – of Papa Legba’s nimble deftness; so evocative of and crucial to the sounding of rhythmic lag, lack, and limp (swing) in black diasporic music and literature, and whose embrace of rhythmic ungainliness make him, for many, the emblem of heterogeneity and cunning resourcefulness – I would be going against the grain of my argument that one process of comprehension is enough to parse what is going on in the music, which is complex and shifting. Roberts’ music isn’t slippery or cunning, deliberately obtuse or evasive; cynical or world-weary but open and honest in its riguor and of putting traditions to work. It is fundamentally generous music, with an open hand beckoning you in. It is the absolute opposite of content, of brand building; of audience targeting. As a listener it is humbling, and as a composer it is inspiring.

In both Matana Roberts and the Moor Mother, what is transmitted, somewhat beyond and beneath the immediate sonic minerality of their music, is a fluid historical dialectic rooted in black radicalism that is inviting, irresistible, and as far as it is possible to be from Green Book / The Help sentimentalism and the droning white enlightenment narratives populated by black archetypes whose strong, silent dignity appeals to the appetites of “colour blind” centrists and their thirst for a universality of experience – and a cadential decent, as the poet J.H. Prynne might put it. Theirs is an art that is resistant to this narrowing of the aperture of black history in service to the capitalist linearity of stoic triumph, always orientated toward redemption (for white audiences) on the back of black suffering and endurance. This kind of commodification of centuries of struggle moves audiences away from a noisy hybrid discourse of simultaneities, where music, storytelling, poetry, and the clamour of their attendant interrelations exist as a kind of quantum tradition that reconfigures itself each time it is encountered. I suppose therein lies her compositions’ “slipperiness” – their integrative and disintegrative processes – but it may be better to propose a slinkiness, in order to admit and take account of the improvisatory playfulness, the joy, the humour, the hope-on-offer, inherent in her music.

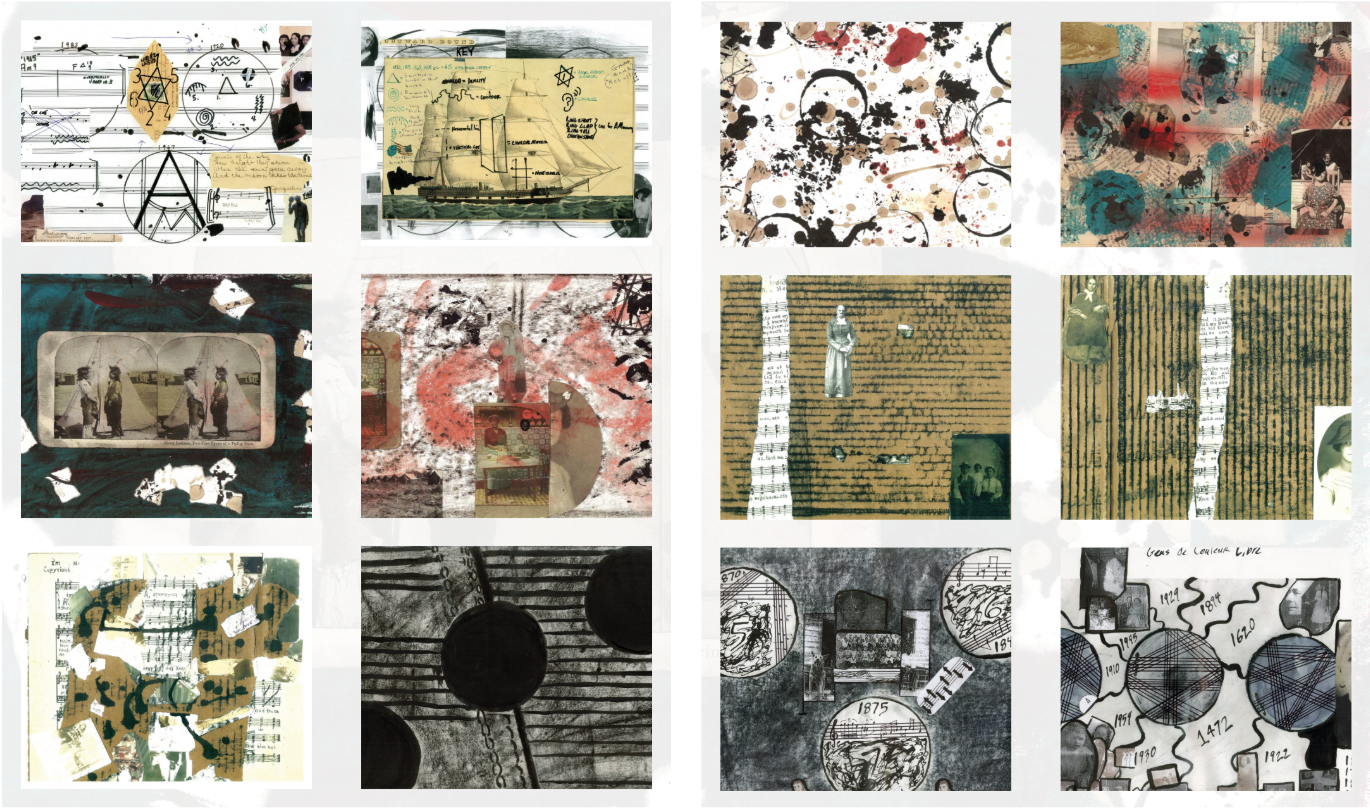

For each instalment of her Coin Coin series Roberts mapped out twelve frameworks (we are currently on number four, Memphis). Each one outlines and calls for different ensembles and sonic palettes, and enfolds different artistic mediums and practises into the work: Chapter Three: River Run Thee utilises visual art and explores feverish electronic processing of the saxophone, Chapter One: Gens de Couleur Libres an improvisatory game piece, and feels the most traditionally rooted in (a multitude of) recognisable jazz tropes, but a thread running through them all is spoken word. The consistency of the dialectic of textual and musical composition in motion throughout the series is remarkable. And there’s a real sensory pleasure at work, a teasing of sounds and words insistent to be fleshed out by breath, throat, tongue, teeth, and lips within and around gasping woodwinds, brass, and reverberating skins. As a listener you become privy to moments of leverage and levity, and goaded towards possibilities of transformation. In Roberts’ third instalment there is a particular flooding of temporal hallucinations that partially image redemptive spaces within which might be moments (to paraphrase the poet Nathaniel Mackey) that give a sensation of qualities beyond conventional assumptions. It’s these glimpses that propel the critical enquiry of her work, exploding nouns to verbs: “I like critical thinking not in terms of critique or trashing things, but in the sense of expansion and generative critique that moves the world and makes change happen.”

When I listen deeply to her music, and I read her liner notes, I get the sense that one might encounter multifarious and endless paths, lost or sent into exile by something undeviating. And when I think about what this immutable constant might be, I can’t help but call to mind the centrist passivity inferred by Barack Obama’s frequent quoting of Martin Luther King’s “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice” (itself paraphrased from abolitionist Minister Theodore Parker), and how it fits perfectly into that wide-eyed American ideal of national destiny, but at odds with the practise of self-actualisation and self-determination of much North American art of the last 150 years, which generally worked in opposition to the rigid formulations of materialist aspiration that folds everything into its own index of prosperity and progress. A blind faith in some unstoppable current of essential goodness – that everything will work out in the end – eradicates and silences the injustices being lived through by many in the present, and recasts them as bumps in the road (Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, the Charleston Nine…) on the way to the fulfilment of (liberal) progress. You can hear this too when people say that ‘history won’t be kind’ about some Machiavellian politician or morally bankrupt public figure; an admission that actual, real accountability and justice is a concept applied only to the least powerful in society. This negation of the present serves to delegitimise and deflate radical efforts of social transformation, and suggests that one only has to be patient, stoic, philosophical – submissive, deferential, dutiful – while attending to any upsets, deviations, and inconsistencies with a soft touch, a gentle realignment back on course, because the path is already predestined towards justice.

Nathaniel Mackey has outlined the execution of self-realisation throughout radical black jazz (one that follows the grain of intuition, failure, and play) as a “deviation from expected narrative accents”, a rejection of submitting oneself to jingoistic providence, and arguing against the establishing of consensuses of values determined by markets, competition, and nationalism by which we read, listen, and analyse, and arguing instead, in the poetry, prose, art, and music we make and talk about, for a condition of sensitivity to an aural oscillation acting between and around the admission of unwholenesses of our histories and historical accounts. This sort of open-eared analysis Richard Quinn describes as “a critique of exclusionary tendencies and a positive project bringing the once expelled back into a shared history.” To that end, Roberts’ most recent chapter Memphis, with its overlapping, often frenetic emergences of diverse black and non-black traditions, clears out a space that allows you to hear this dissonance, disparity, and discrepancy; letting indistinctions and unwholenesses guide the you towards meanings that may have been deliberately or unknowingly severed. That’s where the generosity lies in her music. It’s where it becomes something that isn’t only about African American experience but its intersections with the myriad of other Americas too.

Her ambitious process of panoramic sonic quilting is also a process excavation and tracing, of the interruption and cleaving and reconfiguring of musical, social, and cultural relations. And so it is music that demands you to witness, to congregate and multiply amongst it. In a recent interview with The Quietus Roberts said, “I like idea of witness: we’re all in witness and we’re all in fellowship together. Not in a religious sense. When you put a bunch of bodies in one space that don’t know each other, this vibration of hope sits in the room.” Whilst she describes here the singular experiences of performing live amongst an audience, it seems to apply also to her recording/compositional process, and the ritual of listening to her record at home. I’m ashamed to say my first encounter with her music was relatively recent, but felt like a convening that reignited musical and artistic possibilities that, for me, had slightly dimmed.

In his book The Undercommons, Fred Moten talks about the “refusal of the academy of misery”, the internalised assumption that rigorous intellectual, creative work requires alienation, despair, pain; worn like badges of honour. Quite why many of us are so distrustful of enjoyment and see it as “a mark of illegitimate privilege” is something we urgently need to meditate on. Hope is a virtue that can get so easily lost and dulled by cynicism, and being able to re-establish and elevate it as crucial to creative practise is a fucking triumph we should hold dear, especially when it is communicated to us in ways like Matana Roberts’ music’s fundamental generosity of spirit. And so I want to end on a note of hope, and I’m unsure I can express it better than Fred Moten: “I believe in the world and want to be in it. I want to be in it all the way to the end of it because I believe in another world in the world and I want to be in that.” James Joys

1/3 of Ex-Isles, James Joys is a musician and composer living in Belfast, Europe.