Nadine Shah’s 2017 release, Holiday Destination seethed with fiery indignation and deep despair as the artist reckoned with the inhuman horror of the Syrian refugee crisis. Her remarkable follow up sees the Tyneside musician turning her lens inward and focuses her incisive attentions on more personal, but no less political, frustrations. Taking aim at everyday racism, feckless men and, most pointedly, the concept of identity and the weighty societal expectations that go with it, Kitchen Sink delivers some of Shah’s most keenly observed performances to date.

These songs push Shah’s macabre sound into exhilarating new terrain, oozing dark glamour and sumptuous detail. ‘Club Cougar’ kicks the album into gear with howls and a blaring brass section that emerges intermittently from the track’s loose-limbed percussion. It even manages to wring out the previously untapped funk potential of a sampled sonar ping which reverberates throughout the song.

Lyrically the track finds Shah’s icy inner monologue throwing shade on the swaggering advances of a would be suitor who presumes to have enchanted her with his one sided conversation and ‘flirtatious’ negging about her age: ”Call me pretty, make your manoeuvre, One year younger, call me a cougar. All dressed up, think I did it for you…Your conversation makes me abhor you.”

Confrontations with this kind of quotidian misogyny, as well as unsatisfactory relationships, loom large on the album, not least on the dingy groove of ‘Buckfast’. The track spins the tale of a deadbeat drunk drowning in self-pity and tonic wine, moaning all the while about missed opportunities he feels he was due. Shah’s fast fraying patience is mirrored perfectly by the track’s lurching guitars which spark and sputter like a busted fuse box as her stately alto intones “Now you’re Buckfast pissed. Reciting all the times you kick yourself you missed”.

Elsewhere, Shah contends with the tensions and societal expectations of being a thirty-something British Muslim woman who happens to find herself single and without children. ‘Trad’ sees the artist unpacking her complex relationship with tradition and skewering society’s, and perhaps even her own, attitudes towards ageing, motherhood and idealised feminine archetypes. The songs yowling guitar squalls and motorik rhythms echoing her fraught internal discord and the insistent metaphorical ticking of biology as she sings, “Shave my legs, Freeze my eggs, Will you want me when I am old”.

The hovering guitar drones, stomping beat and snarling punk vocal on ‘Ladies for Babies (Goats for Love)’ take this idea even further, connecting the dots between our culture’s procreative preoccupations with ideas of female servitude and images of livestock markets, “Cause sir chose so wisely, You wanna tame me, Put me in your pocket, Then take me to market”.

The album’s spectacular title track ploughs a creeping, syncopated furrow of tick-tocking guitars, handclaps and piano chords and places Shah’s crosshairs squarely on the racist public who judge “strange faces… whose heritage they cannot trace”. Concluding that the best revenge is living well, she resolves to let haters be haters, memorably dismissing them as a, “Gossiping, boring bunch of bitches!” as buzzing guitars descend on the track like a swarm of bees.

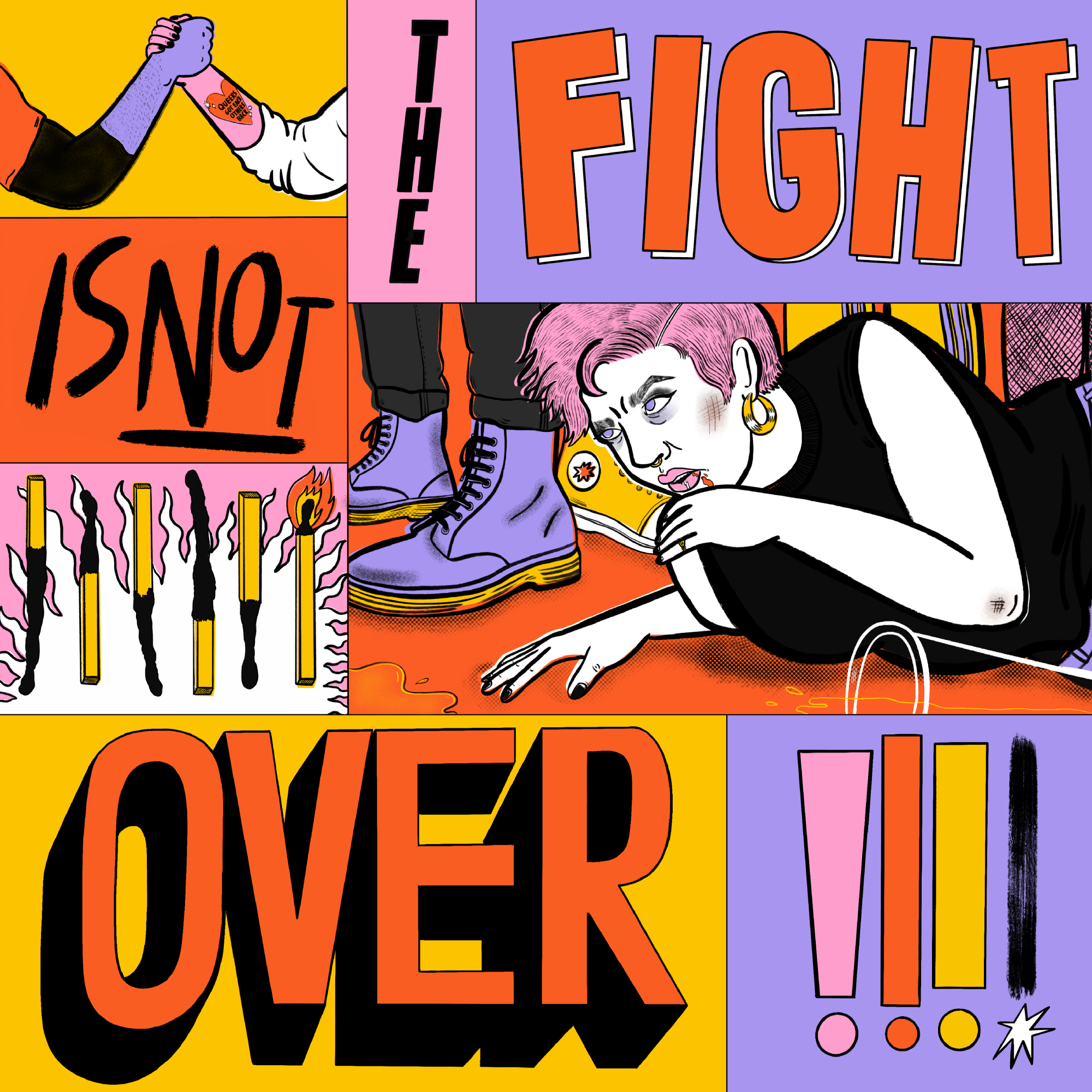

By turns wry and furious, Kitchen Sink surges with free flowing musical ideas and head-scratching melodies that call upon influences as disparate and far flung as Can and devotional music. Most arresting though, is the ease and sophistication with which Shah frames and delivers her unique and razor-edged perspectives on life, love and identity. In a recent interview she noted “I am in no way a traditional Pakistani woman, but I am a version of Pakistani woman, which I’d like others to see…” Kitchen Sink, with its broad spectrum of characters, themes and experiences certainly speaks to that. James Cox