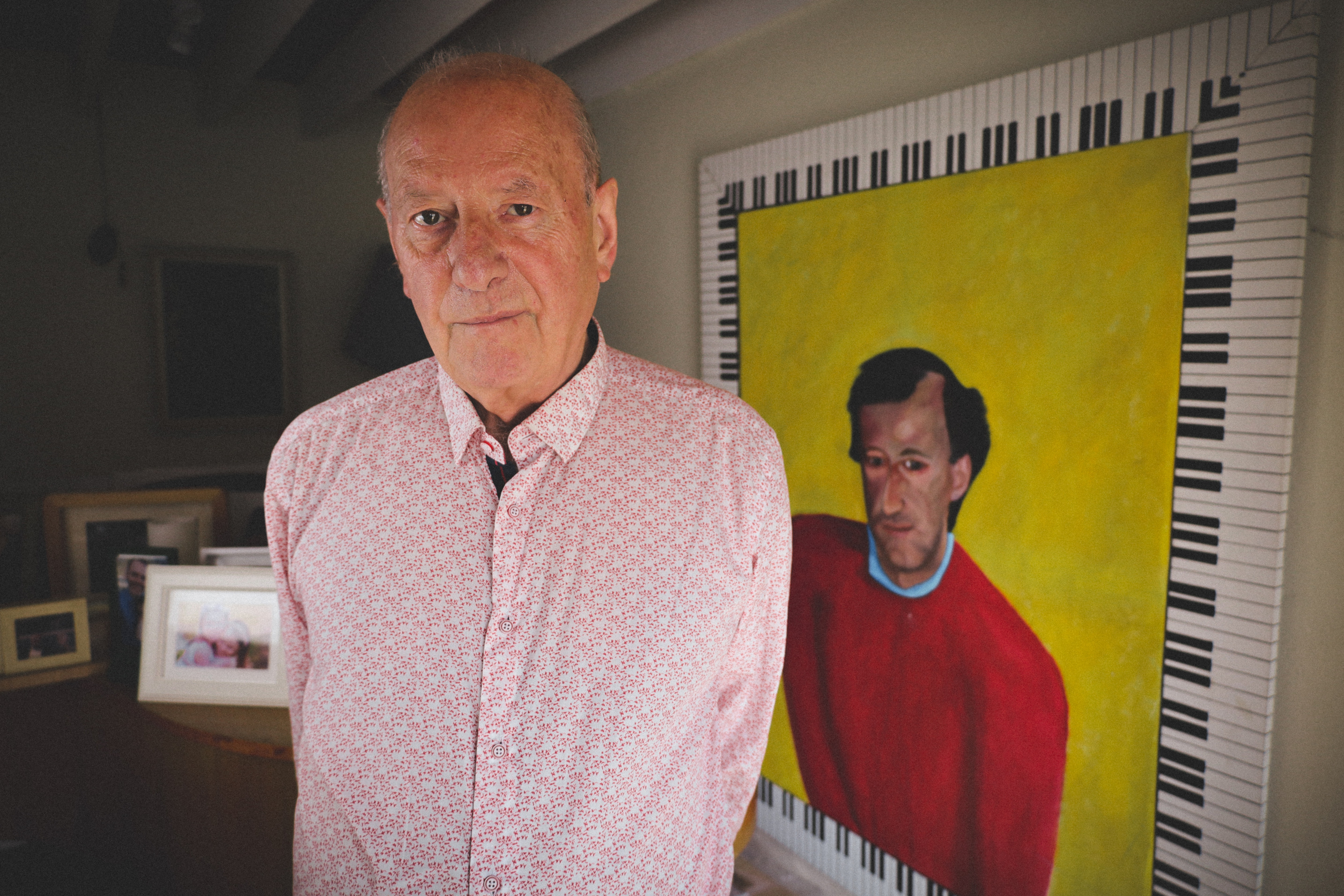

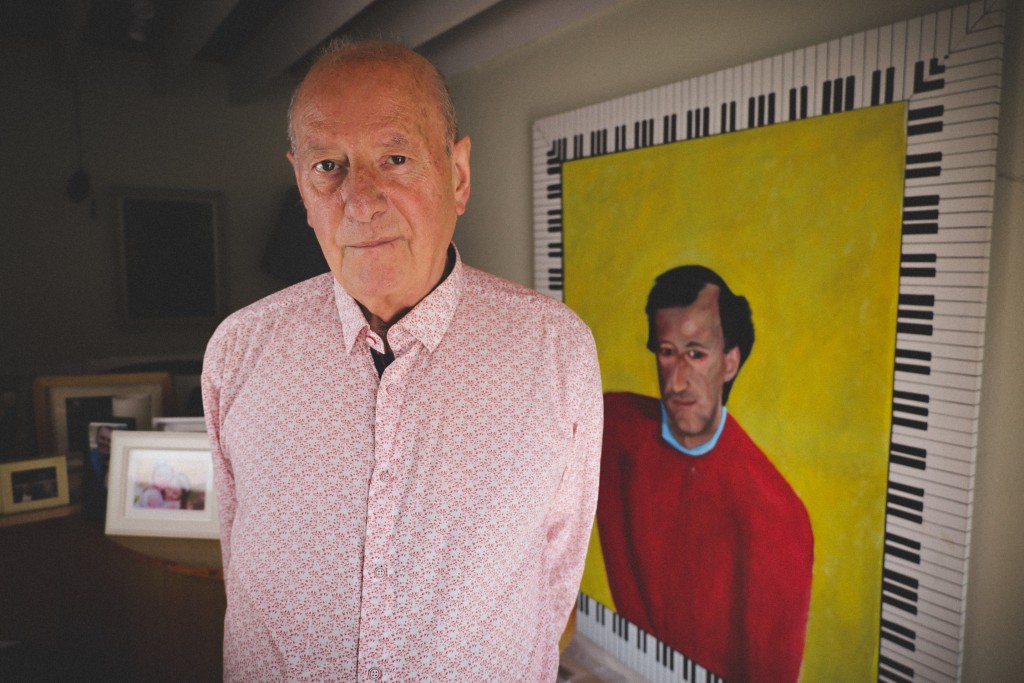

Irish composer and godfather of Irish electronica Roger Doyle speaks about his latest album, Finnegans Wake – Suite of Affections, performing live, science fiction and the creative process

Photos by Loreana Rushe

When Roger Doyle graduated from the University of Utrecht, he was told that he was “the flowering of a seed that was never planted”. It was a poetic summation of his anomalous position on the 1970s Irish music scene, as an electroacoustic composer. What’s more remarkable is that this has been just one strand in his radiating, ever-evolving corpus. For over fifty years, he’s been a force of concerted reinvention, blazing across and through Irish experimental music, pop, theatre and cinema.

In recent months, his many worlds have seen a wellspring. In March, the CD release of the second volume of Doyle’s latest album, Finnegans Wakes – Suite of Affections (2022), a two-part collection of theatrical monologues-cum-electronic music pieces, has been accompanied by the recent reissue of Spring Is Coming with a Strawberry In The Mouth, the 1986 single by Doyle’s and Olwen Fouéré’s theatre company-cum-pop band, Operating Theatre. A reissue of his ambitious Babel (1996-99), an extraordinary 6-hour, 5-CD work encompassing his many different musical languages, is also on the way.

I spoke with Doyle first about Suite of Affections, starting with his lifelong interest in James Joyce. “I read Ulysses as a student and thought it was fantastic. The breadth of the changing of languages and the sheer technique. I put Joyce and Stravinsky together in my head at that time. They’re both born in the same year, moved around between style and languages and idioms and had the most gorgeous technique.”

Joyce would serve as both Doyle’s lodestar and a significant element in many works, from a 1980 stage adaptation of the Sirens chapter of Ulysses, to the writer’s hallucinatory manifestation in the 2016 opera Heresy. The motivation to make an album about Finnegans Wake originated a few years ago. Due to its radical mutation of the English language and the sheer breadth and density of references, Joyce’s last and most challenging behemoth is less a book to be read beginning to end than a strange dimension that attracts but then often swiftly repels readers. This was Doyle’s experience, until passages began to click.

“I found 28 of them; bits that really come alive for a couple of pages. They’re like flares in the night they light up literature, and then like all flares, they fade into the night again and all is dark, and you’re left with sixty more pages of impenetrability, but it’s worth it for those three pages at a time.”

After a period of research, Doyle recruited a range of “the best of Irish film and theatre actors, the best there is, in fact, world standard” from Aidan Gillen to Isobel Mahon, to record these passages and in the process reveal a humour and humanity in what is often viewed as a wholly obscurantist text. They also represent a merging of the worlds of Joyce and Doyle, with veteran Finnegans Wake performer, Barry McGovern making the most appearances, and the seismic And Can It Be performed by Olwen Fouéré, Doyle’s most frequent, long-standing collaborator.

The music itself was composed intuitively but with a couple of aims in mind, including avoiding just “adding a bit of Irish harp”. Using mainly computer software-based instrumentation, Doyle not only achieves a “subtle camaraderie” between his playing and their performances, but a powerful analogy for Joyce’s expansive logos, in its ability to plunge into abstraction: the cosmic reverberations of Nuvoletta, and mimic a plethora of style: the cluster of music hall melodies in Time: The Pressant.

Doyle rooted his ability to work with actors in his experience of theatre, a decades-long wholehearted immersion involving composing music, directing, acting, and managing a theatre company. The mother of this pursuit was partly necessity, originating at the end of the 70s when he was struggling to find support as an avant-garde composer. When asked about the difficulties of finding an outlet for ‘art music’ within Ireland today, Doyle was hesitant to declare the medium dead, but stated that persistent difficulties in bringing classical music to audiences, and encounters with hostility towards the form, are troubling; “I remember Frank Zappa saying, “Jazz isn’t dead it just smells funny”. “The world of theatre is so rich and if I’d just been a composer of classical music, Jesus. It would be like stale air or something. I would be in the museum with the rest of them.”

This diversification can be found in the influence of science fiction on Heresy. I asked Doyle about the genre, and he praised the imagination of Blade Runner and 2001: A Space Odyssey, in contrast to the sorry state of contemporary blockbusters like the latest Avatar, criticising their “boil-in-a-bag” approach “with orchestral music from beginning to end, and [an] incredibly limited use of melody and harmony. Just completely amateurish and thoughtless.”

In regard to his own method, he described an interdependency of improvisation and discipline. For instance, his piano-led solo performance at the Haunted Dancehall—and the same goes for his Flotations show at the National Concert Hall in June—involved complex compositions and timing, so a solid month of rigorous rehearsal was essential. “The opening piece was called Cool Steel Army, and I knew that you can’t just go shilly-shallying into this. You’ve got to launch yourself into this piece and just bang it out, and that’s what I did. I was confident enough to do that because of the month’s rehearsal and it really paid off. The crowd went fucking nuts for it.”

And yet Doyle also stressed the importance of music as something to be stumbled upon, such as during the process of composing Suite of Affections. “I’d switch on the computer, lay my hands on the keyboard and things start to happen. Almost like magic. If you keep at it long enough all kind of chance events and magic happens in the studio.” Within his newest work, In The Dreemplace, a collaboration with violinist Aoife Ní Bhriain set to premiere at the Clonmel Junction Festival on July 1st, Doyle detects old and new threads. It continues his interest in Finnegans Wake, as well an exploratory approach to composition but also “inhabits a strange parallel musical world to my ears, in that it’s one take improvisations, fixed and recorded and scored afterwards, and it’s a different world. It’s like a different animal, a different species of music” A potential new branch then to Doyle’s deeply-rooted and growing tree of life. Ruairí McCann

Delve into a smidgen of Roger Doyle’s sprawling catalog via Bandcamp