A rare jack of all trades & master of many, Belfast-based writer, filmmaker, playwright, screenwriter, theatre director and musician John Patrick Higgins has only gone and successfully written two books. We can’t say for sure, as they’re not yet published, but we can all but guarantee you that they’ll change your life. Or, your know, your immediate awareness of indispensable writing from these shores.

The first of those two books, Teeth: An Oral History, is, we are reliably informed, a bitingly funny story illustrated by the author and featuring a glossary of useful terms, as most of his references pre-date the discovery of fluoride. It’s also published next Monday, 15th April, so you’ll want to continue reading to discover precisely why it you should probably pre-order it now. You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll hopefully not grind your teeth too hard in anticipation of his debut novel, Fine, which is out in November.

Ahead of its release next week – and its official launch at the Black Box Green Room as part of this year’s Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival on 5th May – Brian Coney talks to Higgins about Teeth by way of Mark E Smith, Gerry Adams, Mick Hucknall, Agnetha from ABBA, Scott Walker, Pam Ayres, Tolstoy, Q Tip, Neu! and more.

Photos by Elizabeth Lordan

Hello John. Many congratulations on your forthcoming brace of books. Before touching on your debut novel, Fine, let’s look at your Teeth: An Oral History. Without Googling, I can’t think of a single autobiographical account framed by the calcified structures in question. Am I forgetting something obvious or have you indeed hit upon a wonderful vantage point to tell a story?

Well, as usual, I’ve done very little research. Mark E Smith always claimed he saved the research until after he’d done the writing, only to be delighted, if not surprised, to find he was correct in every particular. It didn’t occur to me there might be a tradition of tooth-based memoirs – Angela’s Gnashers, perhaps – but I was reasonably certain no one had written about my teeth. That, sadly, is no longer the case.

For as long as I can remember, even the word teeth has been synonymous with anxiety; neuroses wrapped in hang-ups held together by dental bridges. Would I be right to assume Teeth confronts this particular phenomenon head-on?

I’ve had earnest enquiries about the content from fervent dentophobes and advised them not to worry. And then I went back and read the book again. You forget, when you’re under the drill, the hammer, the sandblaster, the whatever-it-is-they-can-actually-fit-in-your-cakehole, there are parts of life where this is not happening, whole areas of existence where you’re not troubled by relative strangers putting their hand in your mouth on a regular basis. Historically, the only thing I’ve placed in my mouth has been my foot.

I haven’t swerved the body-horror in this book. There are extractions, there are root canals, there are blood-spattered handkerchiefs and gummy injections galore, and I may still be numb to the grimness of it all. But there are jokes too. I try to keep it light, even as I’m being asked to rinse, spitting my bloody shrapnel into a pristine sink.

Many great writers become so as a means of coping. Did jotting down thoughts and impressions before and after various appointments act as a longer-lasting local anaesthesia to the inconvenience of needing teeth to function as a human being?

There’s nothing in my life, however mundane, that isn’t written down in anticipation of my turning it into something. Mostly it’s a series of mildly, humiliating events from which I learn nothing at all. But from the first session, where the dentist took mugshots of my smile with his forensic camera, and showed me the results, magnified, on a lightbox, I realised I’d entered the realm of nightmare.

I’d been pouting like David Sylvian in photos to hide my teeth (and accentuate my cheekbones) for decades. My smile hadn’t seen daylight since the last Labour government. And here was this nice man illuminating them in front of me, and I knew I had to write about the horror of it. I felt naked and, worse, had no idea how bad they’d become. I’d lost the run of myself. I had the sort of teeth a druid might visit at the summer solstice. Teeth a war correspondent might do a nervous piece to camera outside. I knew had to do something about them.

Writing this book has not been far off an exorcism. Out demon out. And shut the door. There’s a draught.

In the book’s synopsis, you note that you’re an Englishman doing something about life-long bad teeth. In some ways, you’re the opposite of Nigel Farage. With that in mind, can we expect moments of transcendence amid the trepidation (maybe like Tolstoy’s reckoning with his latter-day conversion to Christianity in A Confession)?

Compared to Tolstoy and Nigel Farage in a single question? You give, but you really take away, Brian. There are always moments of transcendence. As you sit there, hour after hour, staring into a halogen halo, while vulcanised fingers worry your gums. It gets boring. I tried Astral Projection, like those people who look down on themselves during life-saving operations, noting the surgeon’s bald spot. But I stopped myself. I was lying back in a chair in Bono-style wraparounds, drooling down my own chin. I don’t need to see that, nobody does. So, my mind went into reveries. I thought about stories and songs I was writing; about satisfactory ways I could win imagined potential future arguments. Boredom is a great tool, and I really couldn’t go anywhere or do anything else, so I used the time fruitfully.

Don’t tell my dentist – he’ll bill me for it.

Earlier today, I discovered that space between one’s teeth is known as a diastema – a word that is also used to describe a musical notation in which the pitch of a note is represented by its vertical position on the page. Which very clumsily brings us to music and how it features prominently throughout Teeth. On the chair and off it, how did the medium alleviate or exacerbate dental dread?

There was music playing throughout each session, a local station which pretended no new music had been recorded since the turn of the century. The most aggressive digging always seemed to be accompanied by Coldplay’s Clocks, which I can never hear again without getting the fear. No change there.

You are – as you’re likely to accept by now – a very witty man. As you are also likely to know, truly droll writing, unburdened by artifice, can be hard to come by. Did you feel a personal responsibility to step up to the plate to write a book that is, as excerpts have hinted, a riot?

You’re very kind, but I wouldn’t say I’m entirely without artifice. The teeth, for one thing, are not nature’s bounty. Funny books are odd, aren’t they? Nobody seems to know what to do with them. There’s a humour section in your local bookshop, but the books there seem to have been designed solely to ease dad’s passage after a heavy Christmas Dinner. I didn’t dream of writing a book as an ornament to a toilet cistern. Comic novels used to have a tradition, but they seem to have fallen by the wayside.

Periodically I ask people to recommend funny books to me and the results are…variable. I find P.G. Wodehouse funny. I loved The Stench of Honolulu by Jack Handey, and Lake of Urine by Guillermo Stitch is achingly funny, beautifully written, and quite often grotesque. There’s a lot going on there. People think I’m joking when I recommend a book called Lake of Urine. I’m not joking.

I strongly associate the dentist with disassociating with Steve Wright (RIP) in the Afternoon, feeling quietly consumed by guilt for simply being there in the first place. Do you reflect on that singular sense of burden in Teeth and, I’m curious, have you ever said “I’m sorry’ either leaving or entering a dental surgery?

I say sorry whenever I enter or leave any room or any person. I love to apologise. I’ve seen C S Lewis referred to as a “Christian Apologist” and thought that sounded like a reasonable job description. Is there a dental plan? What are the hours? There’s quite a lot to apologise for.

I never apologised to my fancy dentist. My NHS one, yes. Showing up in her spotless office with a mouth like a used ashtray just seemed rude, like trekking muddy footprints across a newly polished floor. But I never apologised to the fancy dentist I was paying vast sums of money to. Besides, we got on quite well. He laughed at all my jokes, even the ones I had to mime because he was elbow-deep down my throat in his marigolds.

My first dentist was a dead-ringer for Gerry Adams circa the 1988–1994 British broadcasting voice restrictions. Failing to casually mention the likeness is one of my all-time big regrets. Do you have teeth-related regrets? Or do you feel the less thrilling experiences were all part of the life’s strange road to oblivion?

Mine was more like Gerry Sadowitz. I wasn’t the only one with a foul mouth in the room.

No, my dentist was a very nice man. Boyish. He went to Tenerife halfway through my treatment and I swear he’d had a growth spurt by the time he came back.

I do regret being born with rubbish teeth. And I regret a decade-plus of Tory government throttling the life out of the NHS. It’s a fucking disgrace. But I don’t regret getting my teeth fixed. I want to smile at people. While I’ve still got something to smile about.

I had a bit of a fairly traumatic but character-building front tooth-related incident as an early teen. Did your compulsion to write at length have … roots in your youth?

As a child I obsessively wrote and drew – I had no interest in sport or going outside, the whole place was lousy with wasps and bigger boys – so I would scribble over reams of computer paper my dad would nick from work. In my late teens – despite a desultory appearance at Art College – I stopped creating completely and got a proper job. It would take me another twenty years to start writing again. I think I thought writing was uncool. Or I was embarrassed by it. I was cowed by the bum-clenching cringe of showing effort. Of trying.

As I get older, I feel more and more connected to that infant artist, and less connected to the listless poseur he grew into. Cool is a trap.

Back to music briefly, which popstar(s) deserve highlighting as having superior chompers – and why?

Dave Bowie is the obvious choice. His original, joke-shop vampire set looked like they glowed in the dark. I’ve always admired Agnetha from Abba’s chunky diastema and, of course, the Gibb brothers were mocked for their gleaming, healthy teeth by people with smiles like bombed terrace houses. The Osmonds also received scorn and ridicule for being both Mormons and knowing how to floss. Cliff Richard had a fetching overbite – he could have been in the Simpsons. Mick Hucknall stuck a ruby in his molars, Jerry Dammers had a mouth like a letterbox, and Freddie Mercury had a whole octave span in his gob. Liam Gallagher had his front teeth knocked out by German estate agents. Rock n Roll.

Bryan Ferry was a massive clencher. There’s the pull-out quote. The Roxy frontman’s my pick. He looks like he could go for an afternoon drive in his open top sports car and spend the evening pulling the flies out of his pearlies with tweezers.

If you were allowed to request particular music while undergoing dental work, what would you opt for?

Farmer in the City by Scott Walker. Or Breathe and Stop by Q Tip.

Seeing as you’re also a writer, filmmaker, playwright, screenwriter, theatre director and musician, it’s not reality-flipping to learn you personally provide a glossary of terms and illustrations in the book. Should the Roald Dahl estate be worried?

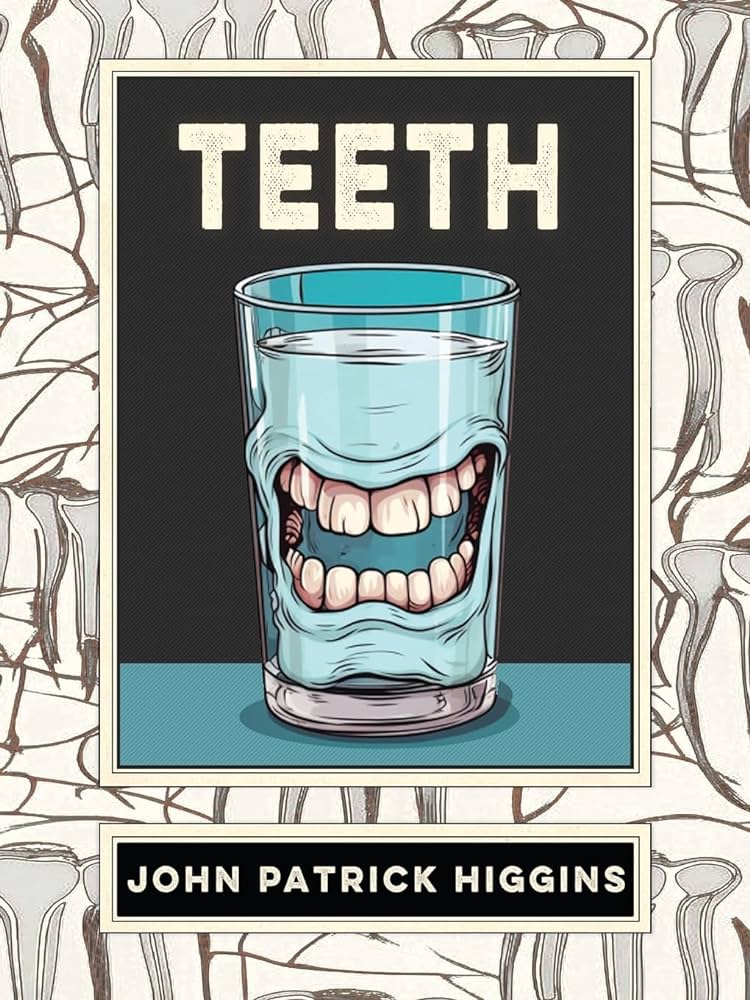

The glossary was a late addition. My publishers are very cool Americans, and I wanted to give them a fighting chance with my endless references to Pam Ayres and Pot Noodles. The illustrations were the publisher’s idea. I’d done some drawings and paintings for the Sagging Meniscus Press house magazine Exacting Clam – a fabulous read, btw – and I think he assumed I’d want to illustrate the book as well. And I didn’t want to disappoint him. I didn’t do the cover though. I wanted someone good for the cover.

It’s by Anne Marie Hantho. I love it.

You launch Teeth at the Black Box as part of this year’s Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival on 5th May. What can attendees expect from what is surely set to be a highlight of this year’s programme?

Me, on a slightly raised platform, reading from the book. Hopefully quite well, as I’ll have practised. Then they can witness me being asked why I wrote a book about my teeth in the Q & A section, the same question phrased in slightly different ways because, well, why the hell would you write a book about your teeth?

I shall be taking questions, but I may not be answering them as I’m not spontaneous and I won’t have prepared the answers. Later, I’ll sign copies of the book and maybe do some DJing.

I think I might be over-lapping with Daniel Kitson in the big room at the Black Box, so tickets are available.

I have an overdue appointment with “Elite Dental” in Belfast next week. As such, I’m almost always thinking of the many things I would much rather be doing that day, like taking a long acid bath or doing the salsa with a newly-sharpened scythe. You strike me as someone who might have some advice in quietening the internal monologue that Steve Wright sadly no longer can. Any pro tips?

Elite Dental sounds posh. I bet they’re very free ‘n’ easy with the zirconium oxide there! When the drill starts a-buzzin’, I head to my Mind-Shed, Brian. Do a bit of pottering about. I’ve always found it easy to disassociate from physical trauma, and you tend find that out about yourself the hard way. Nerdy tedium is a lifesaver in the dentist’s chair. Maybe you could mentally reorganise your vinyl or rank the Neu! albums in order of poptasticness. I try to name the Fall drummers in order, including repeats (hello Karl Burns), but you’ll find your own system. No, you really will. You’d rather be thinking about anything else.

Lastly, your highly anticipated debut novel Fine is set to be published in November. Seeing it italicised like that just screams passive-aggressive agreement but it’s almost certainly nothing to do with that. What is it about and to what extent does it correspond – in any way – to Teeth, which is out on 15th April?

Teeth is about me undergoing a series of costly humiliations over the course of six months in pursuit of a winning smile.

Fine is the story of a middle-aged man encountering a series of flummoxing derailments over the course of a year. He’s called Paul. He lives, anonymously and alone, in a big city, and does a job he’s neither good at nor interested in. He likes music and art, is failing to write the novel he’s been writing for a decade and is lonely to his bones.

It is not, in any way, autobiographical. Paul is a lot taller than I am. And he can drive a car.

The Fine of the title is very much a passive aggressive one. Well spotted!

The book is a comedy pitted, like the pulp in your orange juice, with tragedy. I meant that literally, but it also works for the bands Pulp and Orange Juice. If there were a soundtrack to the book, they might both be on it.