Full disclosure: I was obsessed with this band from the ages of 15-18. I was insufferable to those around me who didn’t get it – and to them all, I apologise – but growing up in rural south Derry, Jane’s Addiction felt like some portal to the unseen. Whether it was the LA seediness or their connection to a more sensual world, it mattered little. Everyone has that band, but going through the typical starter pack of Guns N’ Roses, Zeppelin, RHCP, and Nirvana, Jane’s were the first band that lit the passage to somewhere higher. They were the band that Anthony Kiedis seemed to think the Red Hot Chilli Peppers were – using sex and opiates to mythologise one’s vision of California. Zeppelin nearly got there too, but always pulled you back to consensus reality as soon as Plant euphemised his ‘lemon’, or started delivering more babies than a senior midwife. This would be the start of a journey of discovery to the Velvets, Slint, X, The Minutemen, Sonic Youth, and far beyond. It took maturity to realise it, but it was this rejection of social norms and very visual embracement of one’s inner weirdness, that, like the Grateful Dead or My Chemical Romance in different eras, made them an ultimate arm around the shoulder band.

Back in 1990, the world seemed to be at Jane’s Addiction’s feet. They’d secured cult status, then had one bona fide MTV hit. They’d managed to wrangle greater artistic control for rock bands on majors, being one of the flagbearers for the burgeoning, technicolour new alternative rock movement, a more hedonistic, bombastic take on the genre-mangling going on around the States in what was known at the time as ‘college rock’. It was never really meant to be, although for a brief spark it seemed like it might, but implosion was all but inevitable. Indulgence was in the band’s DNA. Ego and heroin were at the centre of the band, and that combination will always be a Coca-Cola/Mentos experiment for rock groups. At one point, Farrell would demand 62.5% of royalties, leaving the other 3 with a paltry 12.5% – a number which has since been corrected – and the latter was everywhere, from their iconography, mythology, lyrics, to the band’s name itself. So, in 1991, just one week before Nevermind’s release, they played their last show of the golden era. It was the final date of the first ever year of that groundbreaking new touring festival rock, metal, hip-hop & electronica, Lollapalooza, created by frontman Perry Farrell – that perpetual flower child salesman for Generation X. It felt almost like prophecy that their demise would soon give way to a similar, yet vastly different cultural behemoth.

In 1997, there’d be a brief tour in support of a patchy, but worthwhile new outtakes album, Kettle Whistle, with Flea replacing bassist Eric Avery, who for year refused to return to the band, and whose melodic, wandering, but simple basslines were regarded by many as the secret hook of the band. Avery brought a necessary tension and unique melodic sensibility that enabled each member to tilt on their own axis, whether it’s weaving around Stephen Perkins’ jazz-influenced, tribalistic drumming, or laying the groundwork for Navarro’s lead work to soar. That wasn’t something commonplace in music at the time, save for perhaps Mike Watt. Jane’s Addiction would regroup again for two albums: Strays – a solid commercial rock album by 2003’s standards – and the unremarkable The Great Escape Artist – in between which Avery had rejoined and left. Neither managed the lightning-in-a-bottle heights of their original trilogy of the live 1987 debut XXX, 1988’s Nothing’s Socking and 1990’s Ritual De Lo Habitual. Their bootleggy live debut and Nothing’s Shocking felt like an ode to the gender non-conformity, bohemia, and underlying tensions within the eighties LA underbelly, while Ritual was more ambitious again, bringing psychedelia and Eastern influences further into the mix in a work that felt half-familiar, and half sprawling meditation on the less tangible.

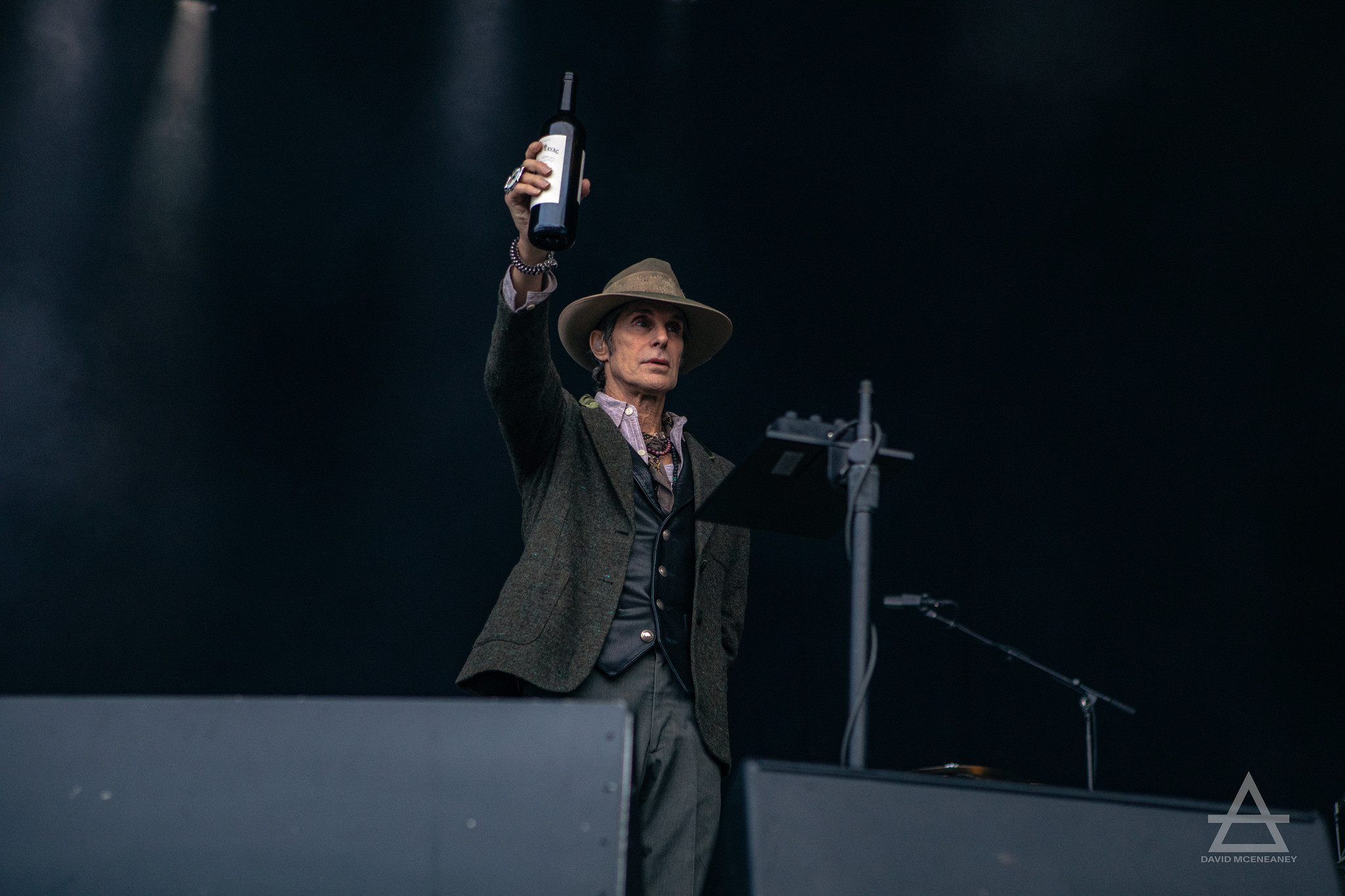

And that brings us to tonight at Trinity College. We’re allegedly witnessing a Jane’s Addiction who seem to have made amends and accepted their place in history. The band have never played Dublin in their history. Primal drums are playing through the PA, and there’s a surprisingly polite – given the band’s reputation – anticipatory audience gathered. Eric Avery and Stephen Perkins emerge – ever the workmen of the band, and a quintessential, frisson-inducing Avery bassline comes in. ‘Up The Beach’, opener of Nothing’s Shocking’ – as well as fellow pioneering touchstone Death Grips’ Exmilitary – plays, Dave Navarro’s trademark cascading guitar comes in, and any fears that this too would be a cash grab are assuaged. Navarro, still pulling off donning his Attitude Era-looking classic hat/shaul/New Rocks, Criss Angel-meets-Nightman schtick, sounds LP-accurate. Perry Farrell, the band’s founder and most senior member, is 65. The dreads, dresses, gymnastics and hard drugs have given way to a hat, suit, lurch and bottle of red wine, but his signature howl is steadfast, and there’s little doubt this is classic Jane’s.

A run of riff-heavy, Reed-esque quasi-philosophising follows about life on the fringes, via ‘Whores’, ‘Pigs In Zen’, Ain’t No Right’, and the peak of Jane’s in that mode, ‘Ted, Just Admit It…’, written about the mania in LA induced by Ted Bundy and media panic. With Perkins & Navarro’s natural chemistry, it still retains the original’s ability to completely combust, spiralling into a kind of unique, discordant kinesis that my father once, unintentionally accurately, described as “making the Sex Pistols sound like Mozart”. Farrell, an equally frustrating and lovable sort, always cut an intentionally messianic figure of his own creation, who believed one hundred percent of his own shit. He calls for working-class unity, and to “fuck the fascists”. He isn’t wrong. He speaks of his support of Ireland on account of loving an underdog. A little patronising, sure, but well-intentioned. That’s frontmen for you.

The pace then shifts, with ‘Summertime Rolls’. It hits its peak, Navarro layering lead-lines that haven’t passed their sell-by, Farrell wailing his trademark ‘Oh-oh-oh’, and everyone is singing as one. Perhaps it’s my own general avoidance of huge shows, or the lens of nostalgia, but I cannot overstate how empowering it is to realise that a song that you felt like only you had a very powerful connection with means the same to other people. During this, I’m offered a swall from a naggin of Jameson and we get acquainted, until the opening chords of ‘Jane Says’ play, and he excuses himself with a “sorry, I’m about to get a bit emotional”. That continues with ‘Then She Did…’, a long-form rumination on Farrell’s mother’s suicide, and one of their finest contributions. Men are spotted drying their eyes, and all of a sudden, it feels like we’re at a Durutti Column gig. Like the band at their peak were, there’s a perfect balance struck between tender and completely facemelting.

There are setlists that feel comfortingly inevitable, and that’s how this is. With nothing other than the nineties industrial-psych of ‘Kettle Whistle’ newer than about 35 years old, they’ve let the sands of time settle upon this discography, and allowed a natural ebb and flow to the set, delving deeper and deeper into the spiritual end of themselves, with ‘Ocean Size’, until we hit arguably the centrepiece of the Jane’s Addiction songbook, the sprawling ‘Three Days’. If they were a Led Zeppelin for Gen X, this was to be their ’Stairway To Heaven’, and after all these years, with arguably each member’s finest musical contribution to the band, its urgent, carnal and dreamlike serenade through an opiate haze remains thankfully intact. This is one of those times we’re thankful there’s no such thing in the Jane’s compositional playbook as soaring ‘too high’.

All this transcendence has been rather emotionally taxing, though, and the spiritual cup feels full. The sun is finally starting to set, and this is a rock show. Banger time is upon us, as ‘Mountain Song’, ‘Stop’ and ‘Been Caught Stealing’ are delivered rapid-fire, zero BPM lost over the preceding decades. For what is ostensibly a druggy band, one thing that is abundantly clear is how much this band means to a certain type of person. Deep cuts are sung passionately by a well-behaved crowd of devotees. Everyone is respecting each other’s space. In sticking to those early, more ‘pure’ songs, the show takes on the kind of feeling of primal urgency that the quartet conjured in their first run, and you genuinely get the feeling this isn’t the end of it.

That’s it, a few drums come out, and they return to those Bohemian roots, and the beginning of the set, with a primal ‘Chip Away’, taken from their first album. They’re all several divorces from beating the drum in a dingy, grotty little LA Club anymore, and there’s a part of you that wonders how much a band like that can mean it in front of an audience at this age, but as the sun sets, and they walk around the stage shaking hands and throwing picks and sticks – no encore, just the set they wish to deliver, in the manner they delivered it. That old familiar arm is firmly around our shoulder for the first time in decades. Stevie Lennox

Photos by David McEneaney