You’re familiar with post-rock, right? Long, usually instrumental tracks that start off quiet and pretty, build slowly then BOOM – erupt into cathartic crescendo, before tailing off with a swooning little coda. That’s post-rock. Beautiful and yes, intense, but formulaic; “alternative” muzak safe enough to accompany football highlights, teen melodramas and Sir David Attenborough whispering feverishly over infra-red footage of rutting beasts.

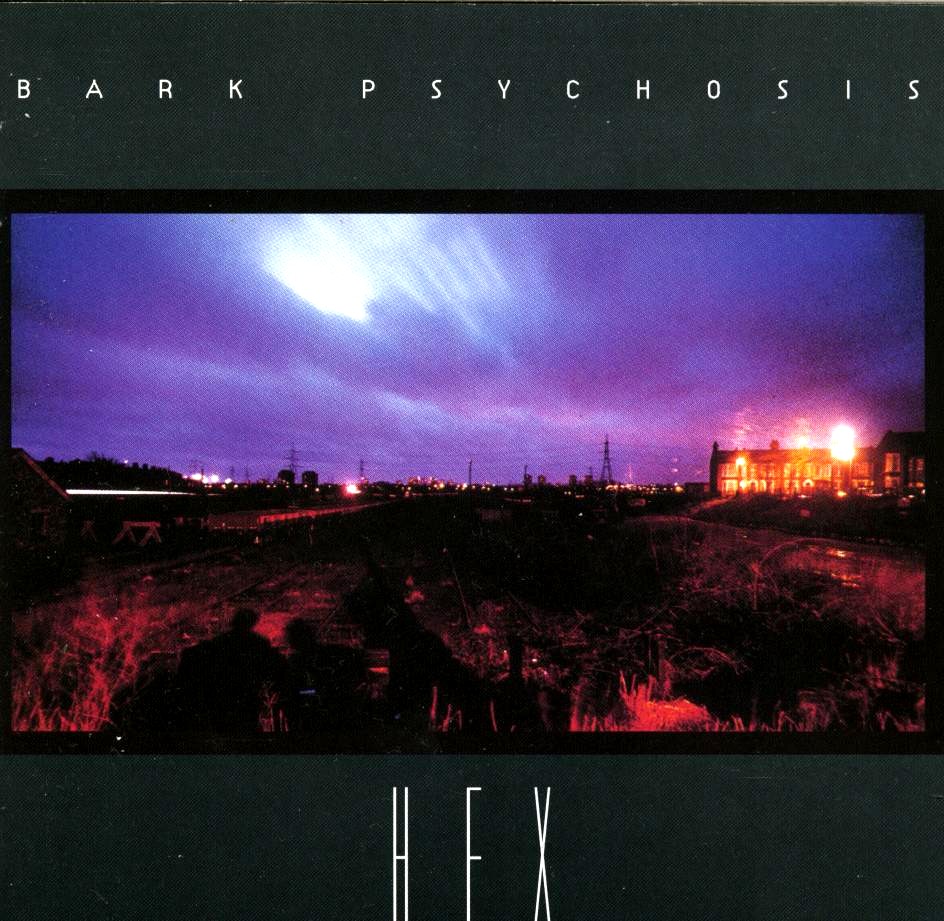

Let’s rewind back to 1994. Mojo hack (and subsequent alt-music historian) Simon Reynolds slips the promo from a new British band into his stereo and presses play. The sounds which ooze from his speakers are alien – an unsettling, nightmarish sonic landscape so far removed from every contemporary chord-bashing, riff-heavy alternative trope that “rock” itself is rendered redundant as a frame of reference. The album is Hex; this music, he ponders, is post-rock. A genre is born.

Fast forward to the present, and in any worthwhile discussion of the genre Bark Psychosis will loom large. Current wisdom will not regard them as the very earliest pioneers – the learned will rightly point to late Talk Talk, Tortoise and of course the redoubtable Slint and their masterpiece Spiderland, among others – but this record is just as musically influential as anything which preceded it. In terms of cementing the idea of post-rock as a genre, its importance is unmatched.

Listening to it now, what is truly remarkable about Hex is not merely that it was ahead of its time, but that it still sounds utterly apart from any era you care to name. The word “timeless” is bandied about too freely in music reviews, but there are a handful of records – Joy Division’s Closer springs to mind, or Nurse by Therapy? – that truly stand apart, no matter how many times elements of their sound are ripped off. This is in part due to the large ensemble of musicians and instruments used in the recording; as well as the standard guitar/bass/drum set-up, you will hear samples, piano, Hammond, melodica, vibraphone, flute, trumpet, djembe (a type of West African drum tuned with ropes) and a full string quartet. Just as crucial, though, is the way the tracks are constructed.

As the delicate piano and strings of opener ‘The Loom’ ghost into earshot, the listener is immediately transported to a darker place, the jazzy percussion playing around a dubby bassline and dense layers of disquieting vibes. The instruments aren’t piled atop one another to manufacture thump and groove in the traditional manner, the myriad elements instead dancing around one another, finding spaces, intertwining in momentary resonances. Graham Sutton’s vocal sits back, restrained yet evocative, drawing the ear deeper into the claustrophobic mix. The tension increases as the music gets quieter (a trick not many of their successors have learned), the track eventually succumbing to fizzing static and sampled clatter. ‘A Street Scene’ somehow manages to be simultaneously danceable and soporific, its louche beat and loping bass anchoring a drifting blend of tremolo guitar, sibilant white noise, strings and horns, before the track dissolves into a gentle guitar reverie.

The hypnotic dub of ‘Absent Friend’, a creepy shuffle to begin with, bursts into life with a glorious guitar arpeggio, a shaft of sunlight amidst the gloom. In Bark Psychosis’ neon-lit world, though, even this is soon corrupted, the track drifting into a spaced-out trance which is ultimately overwhelmed by counter-rhythmic chiming. The eerie, floating vibes of ‘Big Shot’ never allow the listener to settle, constantly shifting direction amid dark, cyclical bass, more chimes and echoing sample sweeps. An incongruously lovely break threatens to transform the mood before bleeding back into the suffocating smog. ‘Fingerspit’, all jazzy instrumental stabs and unresolved builds, is remarkably tense without resorting to the obvious explosive release.

It’s penultimate cut ‘Eyes And Smiles’, though, which has been most obviously stripped and sold for parts by the post-rock factories of today. Eventually swelling from pure-eyed guitar melody into a maelstrom of keening horns, deep guitar reverb and the most impassioned vocal on the record, it’s a virtual template for much of what emerged over the following two decades. Album closer ‘Pendulum Man’ is enthralling, the band patiently erecting an immersive ambient soundscape around a simple tick-tock guitar pluck over ten mesmerising minutes.

As spellbinding as its title suggests, is that rarity – a classic, seminal record whose chronological significance in the grand scheme of musical development is not only matched, but arguably bettered by the undated quality of the music it documents. If this had been released on St Valentine’s Day 2014 rather than 1994, it would still be album of the year. Lee Gorman