There’s a moment on the song ‘1979’ when, after a subdued but ethereal sounding intro, the thumping drums of Jimmy Chamberlain burst in, augmenting the subtle electronic percussion that has hitherto anchored the track. On the one level, it’s just a simple trick of song arrangement, building up an expectation and then subverting it, but on another it’s pure magic, like when Dorothy wakes up in Oz and the world has gone from black & white to colour.

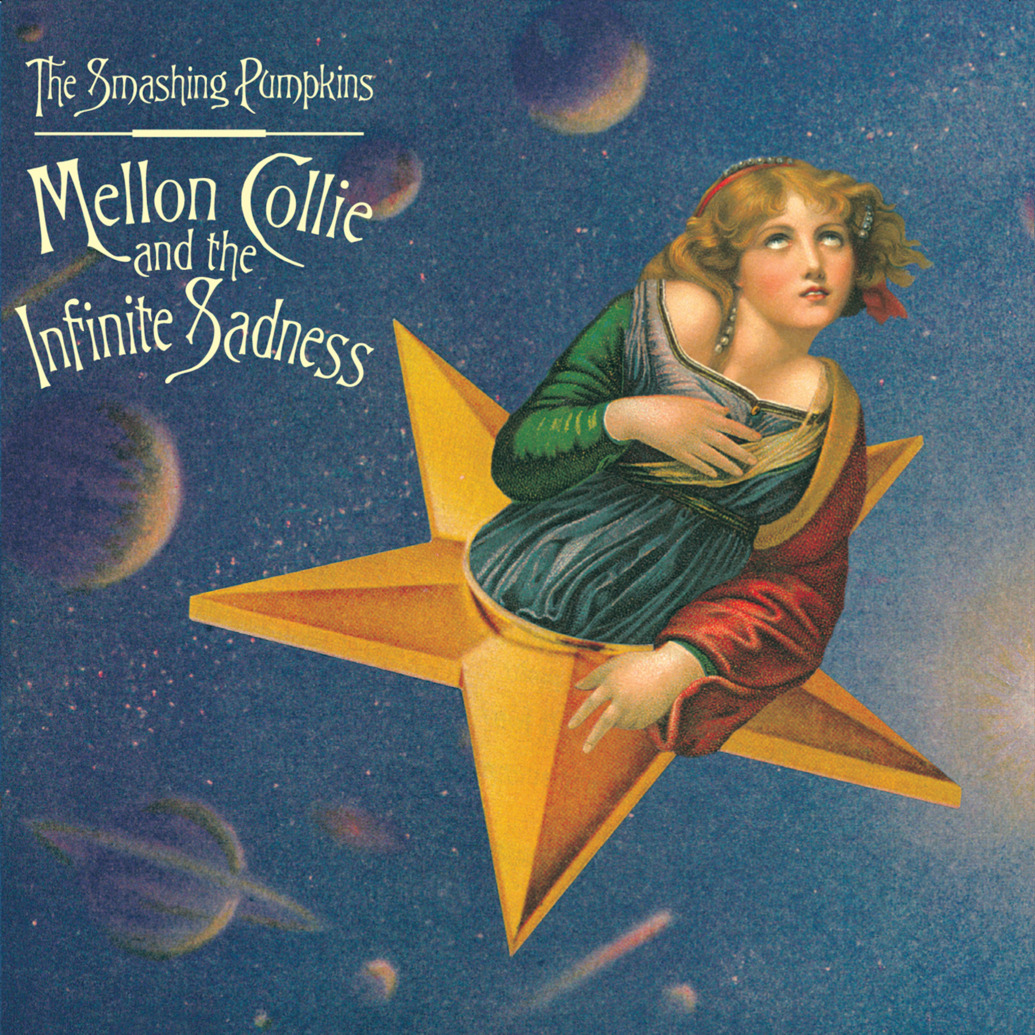

There’s no reason why Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness should work. It’s a double album that came in an era when ‘punk rock’ had finally gone overground in the United States. As the world was swamped with nihilistic, distorted, radio friendly missives from Generation X, Billy Corgan crafted a prog-rock opus that was big on the nihilism and distortion, but equally adept and tender atmosphere, and epic melodrama. By way of comparison, Nirvana’s three studio albums amount to 35 songs, whilst Mellon Collie has 28 on its own. That’s a lot of ground to cover.

But far from being the bloated catastrophe that it could have been, the record manages to showcase everything that is good about the band, distilling it into one mammoth meal. Monumental slabs of riffing? We got ‘em. Shimmering psychedelic dream-pop? Check. Confessional acoustic songs? There, if you need them. Angsty grunge? In spades. And much like Prince when he released Sign ‘O’ the Times in 1987, another double album, Corgan is at the peak of his powers, equally adept at everything he turns his hand to. But rather than proving his genius, Mellon Collie shows that he was a master at knowing his limitations. For an album that is sprawling, Corgan rarely leaves his comfort zone, distilling his influences and ideas into a fairly streamlined formula. The whole way through the album, the Pumpkins are as black as Sabbath, as prog as Rush, and as melancholic as The Cure.

Of course they couldn’t really follow it up, and while Adore is arguably a more affecting album, and the underrated Machina certainly has its fair share of ambition, Mellon Collie captures a moment in time perfectly, and comes closer to a ‘definitive’ statement than anything else they put their name to. Kurt Cobain had died before it was released, and in many senses of the term, grunge had died with him. The UK was in the midst of conducting its own assault on the charts with Britpop, and moping American rock bands with double albums were very much out of vogue. Nonetheless, Corgan conquered the world with the album, tapping into some kind of subconscious feeling that we were all having, as if he’d peered into our hearts and told us what we were all going through.

The video for ‘1979’ captures that feeling. A bunch of post-grunge kids, lost and adrift in the world, hang out, go to a convenience store, and without anything being overt, have one of those BEST NIGHTS EVER that you can only have when you’re a certain age, and you’re cynical enough to be sceptical of things, but open-hearted enough not to shut anything out. That was the Smashing Pumpkins‘ gift to the world, and it’s my hope that somewhere out there right now, a kid is listening to Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness for the very first time, and experiencing everything I got from it when I was at that age. And if that’s true, then somehow the world just became a slightly better place. Steven Rainey