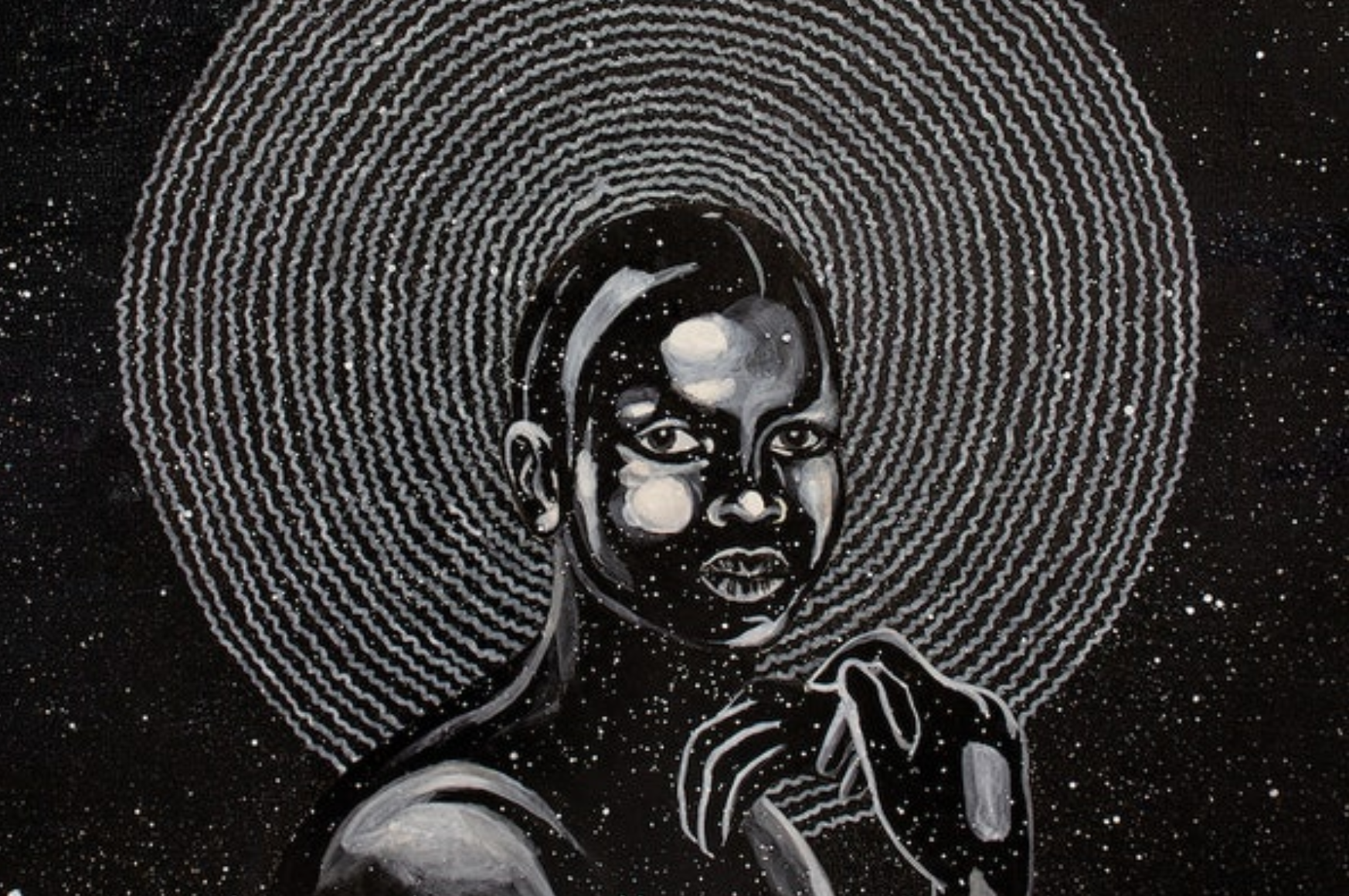

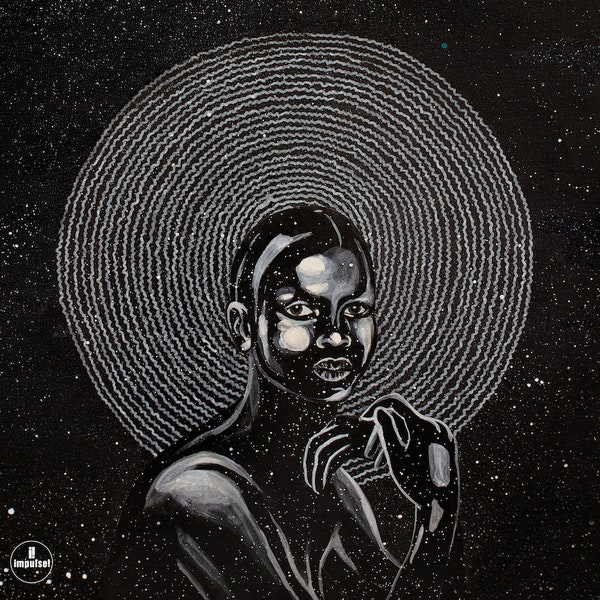

In a recent article for The Outline, “Don’t leave jazz to the jazz guys”, writer Shuja Haider laments on the fact that jazz has, in the eyes of many music lovers, been co-opted by a certain superficial and off-putting fan – the “jazz guy”. Given that the depth of jazz history makes exploration an intimidating prospect, it’s perhaps not all too surprising that many of its most noticeable modern listeners have hesitated to dip beyond shallow, well-trodden edges. For those looking for a shot of adrenaline before diving fully into its vast, exhilarating waters, however, one could do much worse than the contemporary work of Shabaka Hutchings. The bandleader and saxophonist is standing at the forefront of a new wave of jazz, foretold most prominently by the adulation and Mercury Prize nominations afforded to the cosmic pop experiments of The Comet is Coming, and the righteous fury from Sons of Kemet. Now adding to that impressive lineage is We Are Sent Here By History: the second album from Shabaka and the Ancestors.

Hutchings’ work with the Ancestors, who are mainly made up of members from the Amandla Freedom Ensemble, first came from a trip he made to South Africa, which resulted in 2016’s Wisdom of Elders LP. It remains one of the most unambiguously traditional jazz projects Hutchings is involved in, yet the tradition does not weigh down on him or his band. We Are Sent Here By History is practically floating from the pent-up energy simmering within, and, like all of Hutchings’ projects, makes you question why jazz has been culturally pigeonholed in recent decades something stiff and stuffy.

While nowhere as fast as some of the more virtuosic bebop, each piece here captures this excited energy by anticipating each note that’s played, each word that’s sung, yet with the total faith in its musicians that it will all hold together. Opener ‘They Who Must Die’ initially has vibes off Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way: twinkling keys add feelings of dreamy mysticism, but the piece instead takes another path, morphing into focused polemic workout, with vocalist Siyabonga Mthembu daring the musicians and listener both to keep up. On ‘The Coming of the Strange Ones’, the energy is passed around like in a game of hot potato, as an elastic bassline elongates and snaps around the brass bounce. There are moments of surprising tenderness too though. The aptly-titled closer ‘Teach Me How To Be Vulnerable’ drapes mournful saxophone over a framework of impressionistic, Gil Evans-esque piano.

Throughout the album’s vibrant arrangements, the listener’s ear will always return to Hutchings’ saxophone – like the appearance of a classic actor walking on stage whose very presence immediately draws the eye. From the man himself: “I’m not trying to have the energy of someone in a suit standing stationary in front of a microphone giving a nice round sound, I’m trying to just spit out fire”.

This key difference is what sets Hutchings’ work apart from his contemporaries. Rather than drawing in a new audience by appealing to the softer, seductive qualities of his instrument, Hutchings’ saxophone is a vessel to summon the rawness within the soul, in all its beauty and ugliness. Such unvarnished spirit is all too necessary in times like these; at the time of writing, the world is engulfed in pandemic, and sheafs are being torn out from previously-thought unimpeachable rulebooks. the Wheels of History are turning again. In a recent interview with the New York Times, Hutchings states, “We need to start articulating our utopias, articulating what needs to be burned and what needs to be saved”. With Mthembu’s chants on ‘You’ve Been Called’ describing a fire that “burnt the bills/burnt the mortgage/burnt the student loans”, it’s clear where these musicians want to spit the fire first. This is revolution music, and is far too important to be left to the jazz guys. Will Abbott