Like a giddy lover, The Eyes of Orson Welles only has eyes for Orson Welles. Mark Cousins’ latest cinematic essay is a swooning, engaged, delightful dive into Welles’ career and personal life and, in particular, his practice of looking, his visual vocabulary as expressed in mostly-lost drawings and, of course, the construction of those fabulous frames. If the film is also under-edited and at times over-earnest, then this can be forgiven. Anyone who’s ever penned a love letter knows how easily they can get away from you. The Eyes opens with a sealed box, a mystery like Rosebud, retrieved from…

-

-

Even before the passengers disembark at a secret destination in the Fermanagh countryside, the drama has begun. Franz Schubert’s Winterreise provides the soundtrack en route before the bus stops. The door opens. A woman in green overalls gets on. Megaphone in hand, a bandana masking her face, though oddly, with an opening for the mouth. She walks silently down the aisle, scrutinizing the faces as though searching for the guilty party. Silence descends amongst the passengers. Search over, the woman gets off the bus, as do the passengers, who find themselves in front of a green cattle shed or some…

-

Maurice Sweeney didn’t want to make a Spotlight special, lost in the evening television schedule, he tells the audience after a screening of I, Dolours, his hybrid documentary about Dolours Price, the late Provisional IRA volunteer, bomber and hunger striker. He wanted to make a movie. Party it’s strategic: a movie gets a slot at doc festivals like Pull Focus, attracting a packed multiplex audience. Partly it’s a way to use story-telling to do justice to Price’s extraordinary story of a life as a Republican soldier. On this ambition, the often-harrowing film is half-successful. I, Dolours tells the story of the Troubles and…

-

Outlining an ethics of documentary making in The Image You Missed, the late, acclaimed film-maker Arthur MacCaig (via Ernest Larsen’s crisp, twangy voiceover) describes the subject of the lens’ gaze as one who is forced to ‘account for themselves’ — their choices and responsibilities and lived experience. Who are you? And why are you doing what you’re doing? McCauley’s son Donal Foreman, Image’s director and editor, uses his own film to turn the camera’s scrutiny back on his absent father, producing an engaging, clever consideration and critique of MacCaig’s legacy, of political docs more generally, and of the subtle differences between looking at…

-

The word ‘foreign’ is used a lot in The Lonely Battle of Thomas Reid, Feargal Ward and Tadhg O’Sullivan’s portrait of a Kildare farmer holding out against the Irish state’s property vultures. Mostly it’s in the context of ‘foreign direct investment’, or FDI, the economic incentive at the heart of Thomas Reid’s problems. The socially isolated farmer’s home is in the sights of electronic manufacturer Intel, who want to expand their local factory facility. As explained by a representative from Ireland’s Industrial Development Agency, the arm of the state responsible for scouting and securing land for multi-nationals, the farm is ‘really the most appropriate’ site for…

-

Is it possible for a film to be not bad enough? Maybe that’s the wrong way to frame it. Shoddiness comes not just in quantity but in flavour: there’s good-bad, bad-bad, no-budget-bad, cheesy-bad, doomed-from-birth-bad. Producing high-yield schlock involves a precise cocktail of badness. The problem with The Meg, which feels like the frazzled product of heatwaved heads, is in its badness ratio: not enough fun-bad, too much boring-bad. The Meg, in which Jason Statham takes on a giant shark with growling one-liners and a steady harpoon arm, goes for two genre tones, and ends up splitting the difference. One is the…

-

A dwindling genre still pushed by naturally rise-averse studios, the young-adult dystopic takes the us-versus-the-world siege mentality of the average teenager and kits it out with hyperbolic, now-predictable apocalyptic flourishes. A mysterious virus; economic breakdown; savage totalitarianism; stirrings of revolution. Adapted from the first novel of Alexandra Bracken’s YA trilogy with a screenplay from Chad Hodge and direction by Kung Fu Panda’s Jennifer Yuh Nelson, The Darkest Minds pits adults against kids with a savageness that’s almost comic. Youngsters either drop dead, get hunted by psycho bounty hunters, or find themselves herded into concentration camps to scrub boots for sociopaths in balaclavas. Even…

-

“More jokes!” After D.C. and Warner Bros’ ultra-sombre film debuts left them with box office egg on their faces, the cinematic DCU has been itching, ever gradually, closer to the light, well-received populism of the Marvel house style. Justice League’s most human moment was a Josh Whedon gag; Wonder Woman swung for idealism and fish-out-of-water larks; the trailer for James Wan’s Aquaman suggests a dopey beef-bro underwater odyssey, while Shazam!‘s leans hard on the comedy, and seems to work. The memo’s gone out: the sillier the better. By that metric, Teen Titans Go! To The Movies is D.C.’s best film yet.…

-

“I’ll figure it out.” Ethan Hunt’s reassurance, repeated through Mission: Impossible — Fallout, is the mantra of the eternal optimist, one embodied perfectly by Tom Cruise, contemporary blockbuster cinema’s most industrious instrument of can-do energy, only but one of the diligently-spinning cogs in Christopher McQuarrie’s meticulously constructed, if occasionally overwhelmed, return to the Impossible brand. If the traditional, Bondian image of espionage (pre-Daniel Craig anyway) is that of effortless ease — a silencer under a dinner suit, a wry one-liner with alcohol on the breath — then in Cruise we get the opposite: intelligence work as aerobic overkill. Under the instruction of the Impossible series’ five distinct directors (McQuarrie…

-

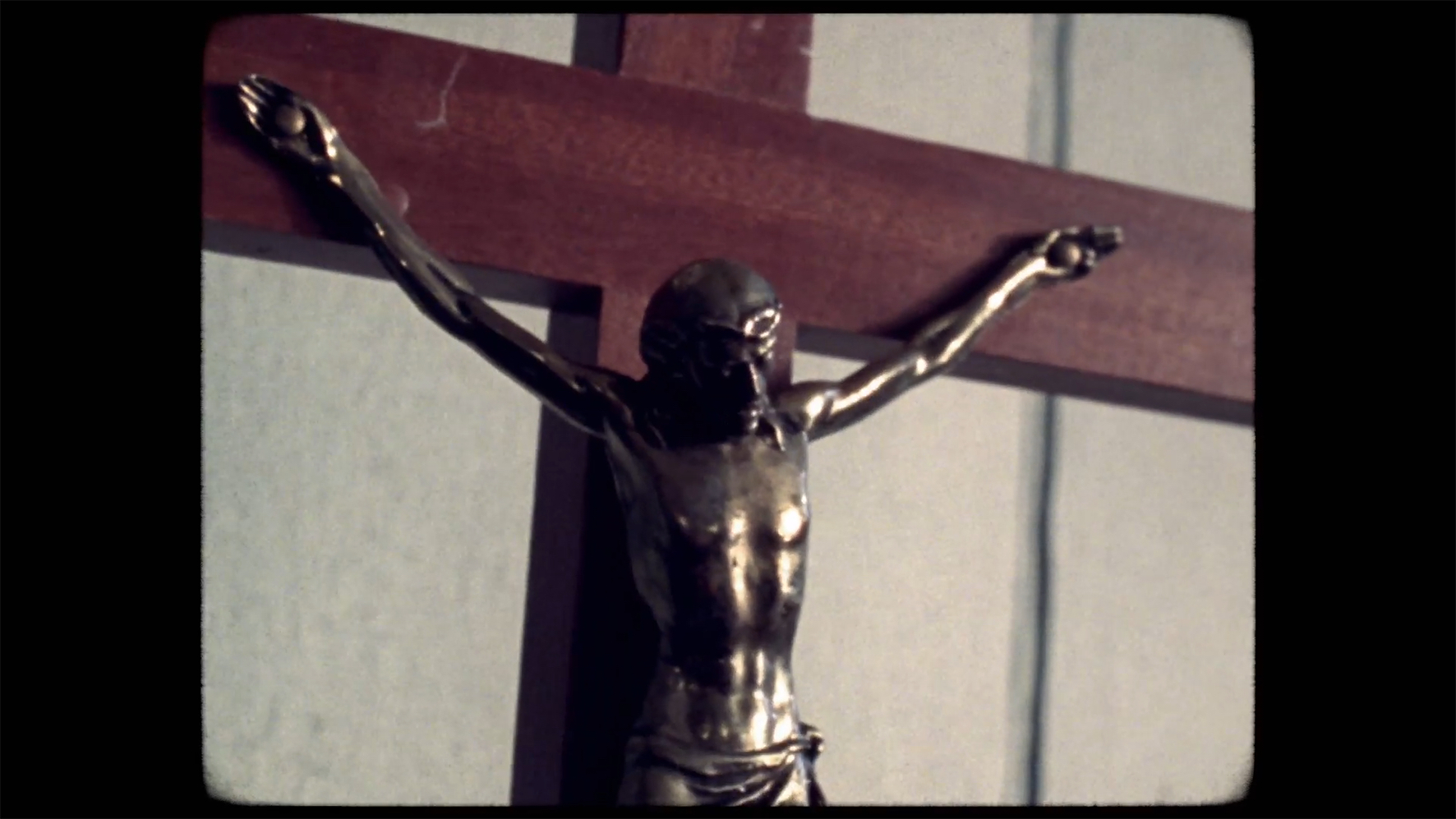

A pregnant woman in chains; the off-screen wailing of child spirits; close-ups of the Virgin Mary with lines of blood down her cheeks, weeping at the sights she sees. The Devil’s Doorway, a Northern Irish horror which last week screened in the Galway Film Fleadh, and received American release through IFC Midnight, is an efficient frightener with local colour and a dense, tight atmosphere of suffering, penance and punishment. You might call it Catholic guilt. The debut film from Belfast writer and director Aislinn Clarke, who lectures in Creative Writing at Queen’s University, and the first NI Screen-backed feature from…