It starts with the sound of twilight, that special moment when the air seems to vibrate, and time stands still. Over plucked acoustic guitar, a breathy voice intones warm whispers, comforting and safe. “The sky’s cruel torch on aching autobahn.” It is a moment that signifies change, and just over an hour later, everything is different. Put simply, this was the end of an era.

In a career categorised by controversies, Adore perhaps remains the Smashing Pumpkins’ most difficult moment. Music, and the world in general, was undergoing a period of transition, a tumultuous decade finally careering to a halt. The Smashing Pumpkins had been one of the titans of grunge, emerging as a Chicago based counterpoint to the plaid-shirted legions emerging from Seattle. But by the release of Adore, grunge had essentially been consigned to the garbage bin of history, partly due to the efforts of the Pumpkins themselves, never an easy fit in the increasingly commoditised underground, their lofty ambitions always straining through the cultivated air of nonchalance that bands seemed required to project.

Their previous album, Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness had been a game changer, a towering monster that had exploded all preconceptions of what the band could be about, firmly establishing them as the true heirs to Nirvana’s alt-rock throne. Led by Billy Corgan, the band had drawn upon their love of classic metal, punk, prog rock, and 80s alternative music to create something that dominated music in ways that no-one could have expected. Proving it was possible to sound like Black Sabbath and The Cure at the same time, the Pumpkins destroyed their contemporaries in one fell swoop, seeming almost untouchable.

The tour that followed proved that, far from being indestructible, they were just as fragile as the rest of us. Touring keyboard player Jonathan Melvoin and drummer Jimmy Chamberlain overdosed on heroin, with only Chamberlain surviving. A gig in Dublin resulted in a seventeen year old fan being crushed to death. The tour limped on and on, with guitarist James Iha declaring that they were bored of rock. Just as it had on Nirvana, it seemed that success had destroyed the Smashing Pumpkins in the aftermath of their biggest triumph.

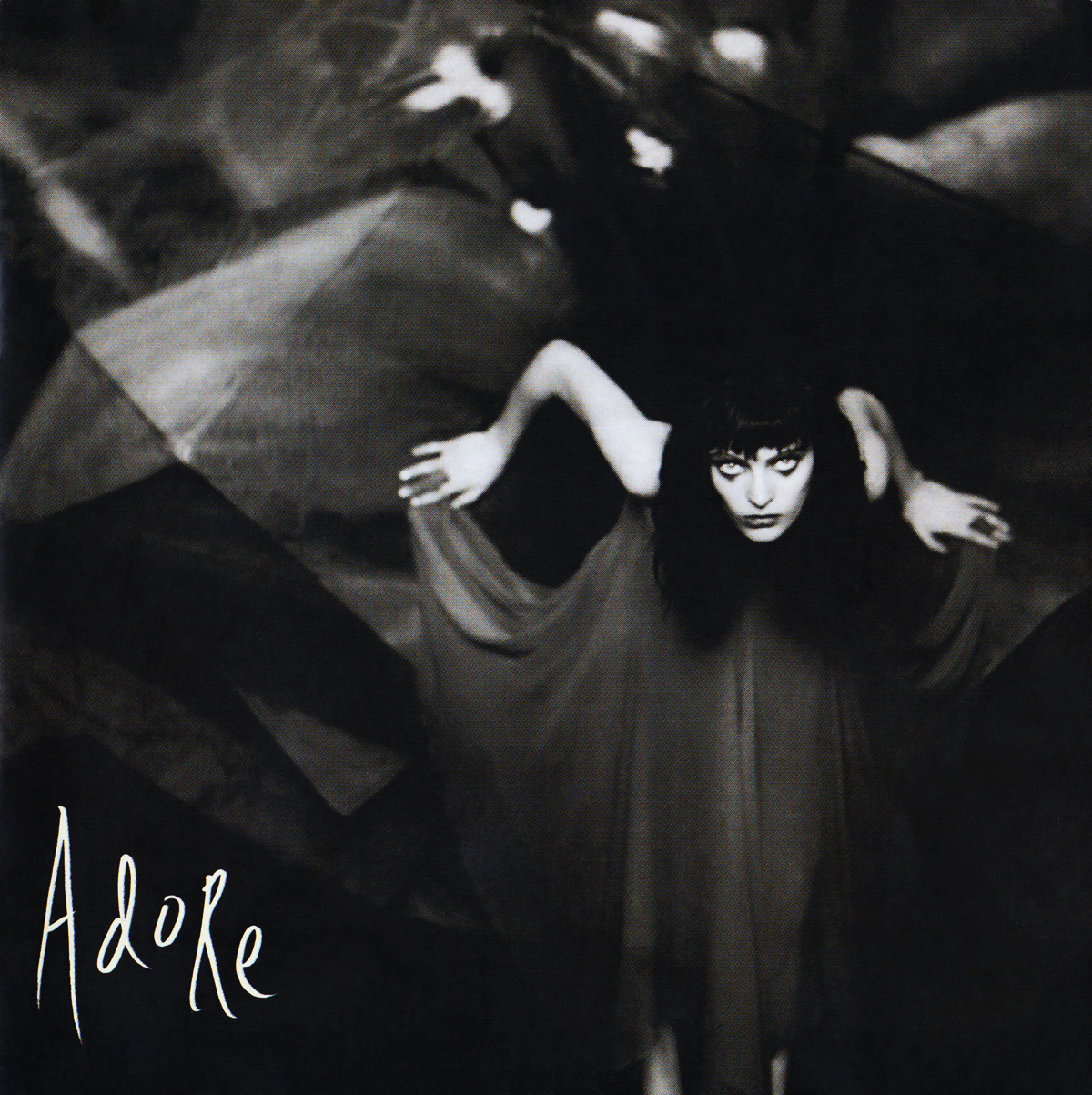

When Adore was released in 1998, the transformation of the band was plain to be seen. Chamberlain had been sacked, replaced by session drummers and electronic percussion. The big stadium rock bombast was a distant memory, a hushed, autumnal sound pervading throughout the record. With the subdued, gothic imagery haunting every aspect of the record’s release, from the black and white photography to the faux-Victorian clothing the band appeared clad in at every opportunity, it was obvious that this would not be a record aimed at the masses.

It was a dangerous canvas for the band to release their new music upon, and one that the notoriously fickle music world didn’t react well to. Where were the huge riffs? Where was the stadium sized angst? Adore found Corgan grappling with his own self-doubt, and offering up a very different side of himself. From the acoustic guitar and banjo of ‘To Sheila’, to the hazy electronic textures of ‘Perfect’, this was a record short on the immediacy of previous efforts, but loaded with meaning and detail. Predictably, this is where the backlash began. If Kurt Cobain’s suicide signalled the end of the American dominance of rock in the 90s, the release of Adore represented a virtual triumph of Britpop’s sunny optimism over American misery and angst. The Pumpkins released one more studio album in their classic line-up, before limping to a sorry end.

But with the benefit of hindsight, Adore stands tall, a glistening and complex record that rewards repeated listening. Elegiac in tone, the record uses simple storytelling to create an atmosphere, the long dreaded electronic instruments mainly used to create texture and tone. The gargantuan guitar structures the band were previously known for were abandoned completely in favour of acoustic guitar and piano, Corgan’s hushed and cracked voice taking centre space. No longer sneering and spitting his words, Corgan seemed to be retracting from grunge’s sense of post-modern irony, openly putting his own feelings on display. Recovering from a divorce and the death of his mother, the songs completely avoid the self-pity and wallowing that grunge had oft been accused of, in favour of deftly constructed sketches that hint at meaning, without succumbing to bombast or overindulgence.

‘Shame’ and ‘Crestfallen’ get by almost completely on atmosphere alone, whilst ‘Behold! The Nightmare’ captures an epic sense of drama, without ever resorting to melodrama. Only ‘Ava Adore’, with its squelchy, heavy bass-synths and radio friendly chorus seemed like a nod to the fans, yet somehow feeling completely at odds with the rest of the record. Without having to resort to the easy tricks of screaming and volume, Corgan was able to craft a record that could be emotionally devastating, without ever raising its voice.

The record struggled to find an audience, with Pumpkins fans bemoaning the lack of rock songs or big guitars, whilst the jaunty swagger of Britpop made Corgan and co seem like a bunch of moping miserablists, hanging in the corner, feeling sorry for themselves. The Smashing Pumpkins appeared to have dropped the ball, just when it mattered most.

In subsequent years, Adore continues to stand alone from both the Pumpkins’ discography, and the music of the late 90s. Certainly, there is a strong case to be made for it being the most accomplished and emotionally involving record the band ever made. But perhaps, more importantly, there is a sense that Adore is a record far more important that its meagre stature suggests. Easily holding its own with records such as Disintegration by The Cure, or Mercury Rev’s Deserter’s Songs, the Smashing Pumpkins managed to make one of the most beautifully sad records ever released, and we are all the better for its existence. When all is said and done, Billy Corgan succeeded in showing the lost and the bruised of the world that pain could be beautiful, and when all is said and done, no amount of planet sized riffs or iconic t-shirts will ever top that. Whether he wants it to be or not, Adore remains his most perfect achievement. Steven Rainey