The men of Sestina, Northern Ireland’s unique early ensemble are striding out on their own tonight, leaving the women, for now, in the wings. For this gender imbalance you can point an accusing finger, into the distant past, at various Papal decrees that forbade women singers in the church.Not good news for aspiring female singers of the time, though we should perhaps spare a thought for the promising young male altos, who were castrated in order to preserve their angelic voices.

Today, happily enough, Sestina relies on natural talent as opposed to radical surgical manipulation for results. This concert, in the magnificent Clonnard Monastery, marks the first time in Sestina’s five-year history that it has performed as an all-male choir – all in the name of authenticity.

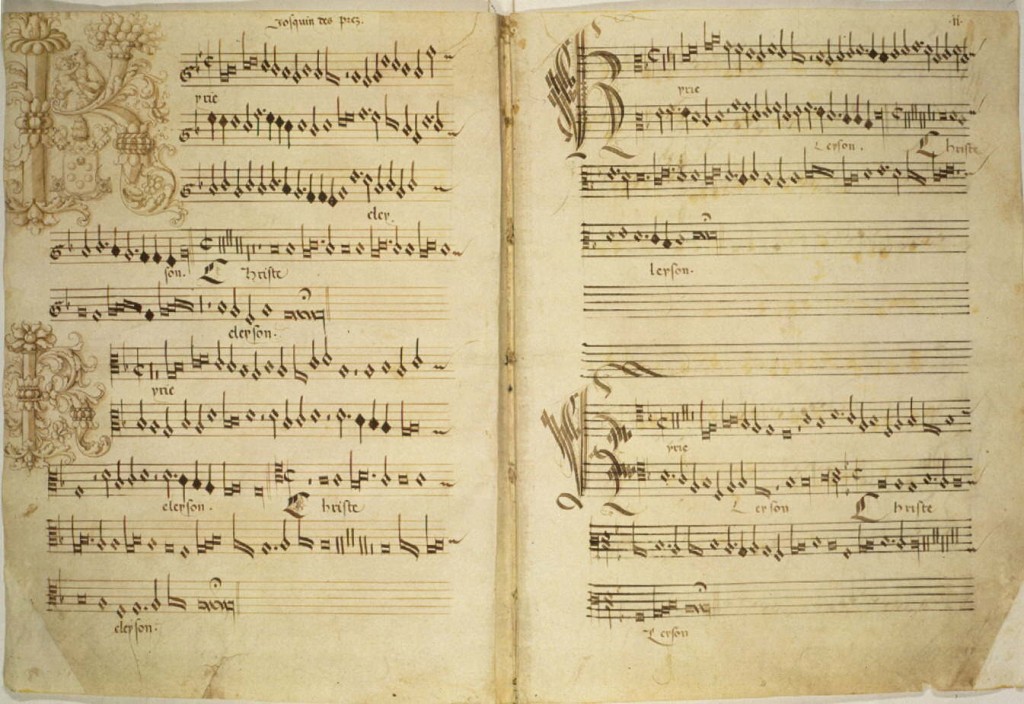

A good crowd is in attendance for an evening intriguingly entitled The Gem Within: Music of Hidden Beauty, a program that features music spanning a century by some of the most celebrated Renaissance composers – Josquin Desprez, Cipriano de Rore, Thomas Tallis and William Byrd, amongst them.

Sestina founder and internationally renowned counter-tenor Mark Chambers, strips away some of the mystery by revealing to the audience – at various points in the evening – how all the featured composers used mathematical principals in their art to configure hidden Cannons (repeated musical devices), hidden textual messages of a religious/political nature, or hidden layers of melodies, stretched and shortened in a way that predates contemporary software enabling such sonic manipulations to all and sundry, by half a millennium.

Clear thought has been given to choreography, as from the get-go the eight voices – alto, tenor and bass – operate as cells, both numerically – with a voice or two dropping out according to the requirements of a particular piece – and spatially, with the ensemble, at times, utilising the length and breadth of the monastery.

For the opening ‘Christe qui lux I’ , a hymnal offering by English composer Robert White (1538-1574), Sestina occupy front and back of the finely appointed monastery, engaging in call and response. The cell comprised of bass, baritone, tenor and an alto voice moves gradually up the aisle, eventually uniting the choir.

Only when the choir is in close proximity, at whatever point in the aisle that may be, or to the lucky ones positioned in the front rows, do the finely woven sonic threads reveal their full glory. On stage, as it were, when the choir is face-on to the audience, the sound, wonderful as it undoubtedly is, escapes heavenwards all too quickly.

There are two pieces by another English composer, Thomas Tallis (1505 – 1585): ‘Loquebantur variis linguis’, a Pentecostal motet for seven voices is a boldly conceived, babbling mosaic that would probably be considered avant garde were it composed today; ‘Misererre nostri’ is an extraordinarily complex series of four overlapping and repeating cannons executed at various speeds. It sounds daunting on paper and quite exquisite in the flesh.

Another early highlight of the first half of the program is the second part of Cipriano de Rore’s ‘’Missa Praeter Rerum Serium’, an epic work which straddles the program in four distinct chapters. De Rore (1516-1565), carried the baton from Desprez and both would have influenced Claudio Monteverdi. The mass contains a hidden hymn of praise to De Rore’s patron, Duke Ercole that possibly only a Latin scholar with very big ears – to borrow jazz terminology – could decipher, but all can appreciate the delightful juxtaposition of alto and bass voices and a narrative that climaxes strikingly.

Motets by William Byrd (1540-1623) come either side of the interval, with ‘Ne irascaris’, for five voices, containing a veiled lament on the persecution of Catholics in Elizabeth I’s Protestant England. In what were extraordinarily intolerant times the mere fact of non-attendance at church could result in imprisonment. Practising a prohibited school of faith could result in death. Byrd, a Catholic, was in Queen Elizabeth’s good books, otherwise his risqué stance could potentially have seen his head become acquainted – briefly – with the guillotine.

His motet ‘Tristitia et anxietas’ is particularly affecting, Sestina moving from somewhat mournful sonic terrain to an incantation of hope. ‘Libera nos I’ a slow, mellifluous hymn by John Sheppard (1515-1558), rounds out an enchanting program on an optimistic note.

Once more, the choral group splits into two cells and trades back and forth, one anchored at the head of the church, the other moving in stages up the central aisle. Once more, proximity to the singers enhances appreciation of the art inherent in such complexly woven compositions and in the sheer beauty of Sestina’s delivery. Glancing around the pews, every head it seems is bowed, or cocked heavenwards, in complete meditative contemplation of Sestina’s mesmerizing musical alchemy.

Sestina hasn’t recorded as yet, though it surely must, as all great ensembles demand documentation.

There may be no better time too, for in an age of increasingly genre-less music, where algorithms predict, even mould our tastes, creating playlists where genre and historical era are trumped by the music’s affect, it’s easy to imagine Sestina popping up alongside harmonists like Simon and Garfunkel, The Beach Boys, Crosby Stills and Nash, New York Voices, Lady Smith Black Mambazo and Hudson Taylor.

Only when the borders, imagined and otherwise, that surround Renaissance choral music dissolve, will this heavenly music reach the wider audience it deserves. Ian Patterson

Alto: Mark Chambers; Joseph Zubier. Tenor: Matthew Long; Matthew Keighley; Peter Harris. Bass: Aaron O’Hare; Brian McAlea; William Gaunt.