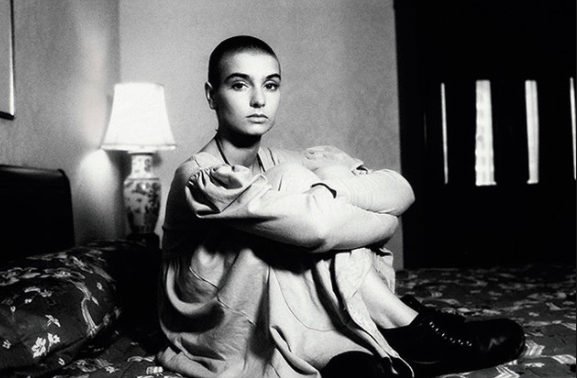

In 1989, American audiences were formally introduced to Sinead O’ Connor. To the opening chords of ‘Mandinka’ the 21-year-old from Glenageary strode confidently across the gaping stage of the 31st Annual Grammy Awards; completely alone, briefly wiping her hand across her mouth and gazing out into the darkened crowd, unfazed. Torn jeans and Dr. Martens, she cut a striking image of unconventional female beauty, strength and unmatched musicianship. Sidestepping and shuffling unperturbed across the stage and ultimately the threshold of global success, O’ Connor at this time appeared to bookmark the redefinition of what it meant to be an Irish female musician.

In the near twenty years since this performance the evolution of that demographic has been slow yet steady, and as O’ Connor signposted, totally untraditional. With the premature passing of Dolores O’ Riordain, it’s difficult not to dwell on the impact Irish musicians have had on the international music playing field, least alone the idiosyncrasies of it’s female affiliates.

Irish female musicians have never fit into the mold of the squeaky clean, choreographed pop star, the template that has been steam rolled and recreated in UK and American music labels tenfold. Similarly, they have never depended wholly on their sexuality to sell records. Perhaps this was and remains a direct result of the conservative Irish undertone or more realistically a natural intuitive inclination, reflected too in the female musicians that have followed suite. O’Connor fought this pop image from the very beginning, shaving her head the moment her record label threatened to exploit her femininity for record sales. She rebuked the homogenized image of what it took to be a woman, especially in pop music, and turned it on its head. Yet she saw her beauty as something of a liability, worryingly admitting in an interview that she “always had that sense that is was quite important to protect myself, make myself as unattractive as I possibly could”, astutely identifying the vulnerabilities in female allure. By doing so, she created an almost impenetrable façade in the early days. Her tumbling streams of consciousness during interviews prickled with youthful cynicism and criticism; those glaucous, sharp eyes an opening into an expressive mind truly only accessible through her music. “I never make any sense when I’m speaking, the only time I make sense is when I’m singing” she once conceded.

O’ Riordain in her own way fought against the tide, her brazen attitude and unashamed lyrical accent identified an individuality insurmountable by any degree of traditional fame. The Cranberries shattered expectations and O’ Riordain alone became an icon of unique female identity in the 1990’s. At a time condensed with fierce female rock musicians, her jagged bleach buzz cut and razor tongued lyricism separated her from the crowd. O’ Riordain’s social commentary came at a time that needed a female voice. ‘Zombie’ became a fearless, humane protest cry to the Warrington bombs of 1993, while ‘Dreams’ was and still is Ireland in a nutshell, painting a scene of ‘90’s Éire all mismatched woolly jumpers and feelings of optimism.

Yet what shaped these artists and what has followed their trajectory to define female musicians in Ireland today? For O’ Connor and O’ Riordain, their early lives echoed an Ireland of a different tone, yet strangely not totally unlike the Ireland we see today albeit with some political progression. Perhaps it’s the stark brutal past from which Irish women have evolved – the totalitarian control over the very essence of their femininity and reproductive rights that has shaped women, their responses to the world and their music, both in the past and present. Or perhaps it’s the underlying thoughtful essence of Irish feminism, a quiet yet resourceful power, astute and aware of possibilities and limitations yet equipped to deal with both.

While O’Connor’s upbringing hugely impacted her outlook on the world notably in face of the Catholic Church, O’Riordain echoed the sentiments of young Irish girls growing up within a rural backdrop – her Limerick was the town or village we all recognized. Their adolescent years were shrouded in the prudish attitude Irish people had, or pretended to have, towards sex. Purchasing condoms required a medical prescription and an added element of shame up until 1985, with Charles Haughey laughably describing the 1979 Act as an “Irish solution to an Irish problem”.

Is it this attitude that deviated Irish female musicians from utilizing their sexuality in creative endeavours, something that has continued to this day, or simply strengthened their ability to harness the focus elsewhere.

O’ Connor and O’Riordain challenged stereotypes and acted as gatekeepers for Irish females to challenge, debate and evolve. They did so completely separately, aware of comparisons and similarities made between them, yet remained on their own unique trajectories. While Irish female musicians like Enya, Mary Black, Wallis Bird and Lisa Hannigan have commandeered their own careers somewhat individually, there is a turning tide in the Irish music scene, one in which politicized, unharnessed female creatives are swelling in their masses united and together.

While the discourse of reproductive rights and sexual expression remain hot topic in 2018’s Ireland, female musicians continue to unfurl the strength of underground movements to create music with unique perspective and integrity. Twenty year old, Dublin raised Bonzai (Cassia O’ Reilly) is the newest unconventional Irish female artist to cement herself in the public musical psyche. A nuanced blend of neon-electric R&B and soft-hued pop interlinked with Mura Masa’s production has seen her spark international interest. Garage ensemble Pillow Queens are infectious homegrown electricity; a quartet of strong-willed identity echoed in their unabashed Dublin accents and harmonized musicianship. While the likes of Farah Elle, Soulé, Mongoose, Hvmminbyrd, and Barq have extended way beyond the parameters of musical expression built by O’ Connor and O’ Riordain.

The growth and undisturbed lineage of Irish female musicians has resulted in a tumbling array of acutely progressive expressionism. While O’Connor and O’ Riordain’s career’s were punctuated with political activism and opinion, the former building and in ways corrupting her career with such defiance, this politicized undertone has never left Irish female musicianship. Today’s Ireland, in face of the Repeal the 8th campaign, has seen an uprising of female unity like never before and has created a modern discourse against which female musicians can not only set their tune but harbor confidence in their ability. An Irish female musician’s place on the global stage has shifted, and when one watches that 1989 footage of O’Connor it’s difficult not to acknowledge how precocious she was. The waves of change are crashing unashamedly on the shore of the Irish music scene, and female musicians stand hand in hand ready to dive in. Rebekah Rennick